Even as some astronomers start shoveling dirt on the much-heralded "first potentially habitable" alien world – a planet called Gliese 581g – its co-discoverer is vigorously defending the find.

Since a team of astronomers — led by Steven Vogt and Paul Butler— announced the discovery of Gliese 581g last fall, several research groups have conducted studies casting doubt on the planet's existence. For a while, Vogt kept a relatively low profile, hoping the debate would play out in the scientific literature.

But that has not happened — and the doubting studies continued to receive considerable media attention. So now, Vogt has decided to speak out strongly in defense of Gliese 581g.

"In the past month, I have been contacted by reporters who have noticed that the media coverage of our Gliese 581g result has now turned decidedly pessimistic and personal," said Vogt, an astronomer at the University of California, Santa Cruz. "It is time to respond."

Making the find

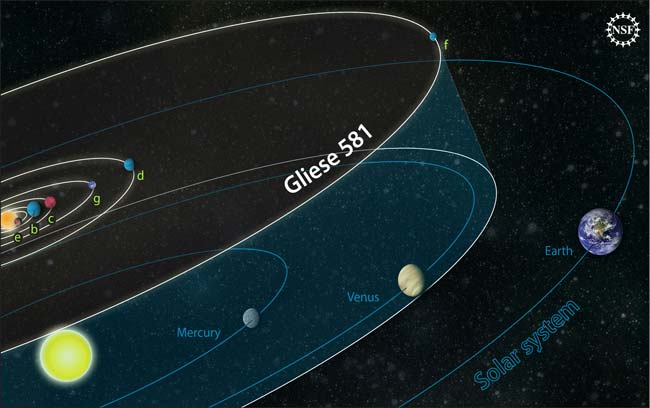

Vogt and his team announced the discovery of Gliese 581g on Sept. 29. The planet, about 20 light-years from Earth, is the first rocky, roughly Earth-size alien planet found to orbit its star in the so-called "habitable zone" — a just-right range that can allow liquid water, and perhaps life as we know it, to exist.

The researchers also said they found another planet called Gliese 581f, located farther away from the host star. The two finds increased the number of known planets in the Gliese 581 system to six (four others were previously known).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Vogt and his team found 581f and 581g using the so-called radial velocity — or Doppler — method, which looks for tiny wobbles in a star's movement caused by the gravitational tugs of orbiting planets.

To detect such subtle movements, the researchers looked at data from two different instruments: the HARPS spectrograph, on a telescope in Chile, and the HIRES spectrograph, on Hawaii's Keck Telescope.

Doubting the find

The tantalizing alien planet discovery soon received a lot of attention, from both the media and other researchers. One group of astronomers, led by Michel Mayor of the Geneva Observatory in Switzerland, performed a follow-up investigation in an attempt to confirm the existence of Gliese 581g.

At an astronomy conference in October, the Swiss team announced that it could not confirm Gliese 581g or 581f in an expanded set of HARPS data.

Two more recent studies reached similar conclusions.

In December, a research group led by Rene Andrae of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, submitted a paper asserting that Vogt's team incorrectly assumed the Gliese 581 planets have circular orbits.

And in January, Philip Gregory of the University of British Columbia submitted a paper in which he re-analyzed the available HARPS and HIRES data using Bayesian techniques — a different statistical method than Vogt's team employed.

Gregory found no reliable signal from Gliese 581g and concluded that the Gliese 581 system likely consists of four planets with elliptical orbits, not six with circular ones.

These more recent studies have led some astronomers to conclude that Gliese 581g most likely is not a real planet.

"It's a goner," planet-hunter Geoff Marcy, of the University of California, Berkeley, told SPACE.com last month at the winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle. (Marcy was not involved in the Gliese 581g discovery, or in the follow-up studies.) "It doesn't exist."

Defending the find

Vogt said that he welcomes scrutiny and follow-up studies by his colleagues as a vital part of the scientific process. But he doesn't think that the critics have made a conclusive case against Gliese 581g.

"We stand by our data and results, and are hard at work obtaining more of our own data on this system," Vogt told SPACE.com in an e-mail interview.

At the moment, Vogt added, his team is "confident that the present HARPS + HIRES data set (as published by Vogt et al. 2010) contains unambiguous and statistically defensible evidence" for both 581f and 581g.

Vogt noted that the Swiss team reached its conclusion after looking only at observations made by the HARPS instrument, ignoring data from HIRES.

"We were very clear in our paper that the combined information of both the HARPS and HIRES data sets was needed to detect and characterize the very weak signals of planets f and g," Vogt said.

While Vogt's team published its discovery of Gliese 581g in the peer-reviewed scientific literature — standard research-vetting procedure — the Swiss team has not yet submitted a paper, he added.

"Until the Swiss HARPS team comes forward with a peer-reviewed paper in the scientific literature that contains either new data, or a new analysis, any claims they make against our findings have no legitimacy," Vogt said.

Debates about statistics and assumptions

Vogt also takes issue with the follow-up study led by Andrae (of the Max Planck Institute), which dings the discovery team for assuming that the Gliese 581 planets all have circular orbits.

That's unfair, because his team did indeed consider other, more eccentric types of orbits, Vogt said.

"We made it very clear in our paper that, while we presented an 'all-circular' solution, we explored literally hundreds of non-circular orbit models, with one, or several, or all eccentricities allowed to vary in the solution," Vogt said. "In the end, we concluded that no eccentric solution was any better than a simple 'Occam's Razor' model of all-circular orbits. Thus, for brevity, we chose to simply show the all-circular case."

Gregory's study shouldn't be taken as gospel, either, Vogt said.

"With all due respect to Dr. Gregory's acknowledged long experience with Bayesian techniques, I find several serious weaknesses, indeed probably even flaws, in his methodology, that have, I believe, led him to the wrong conclusion," Vogt said.

One of those weaknesses, Vogt said, is Gregory's decision to add an extra uncertainty component to the HIRES data, giving it less weight than the HARPS observations. And Gregory's analysis doesn't properly take into account the gravitational effects the Gliese 581 planets exert upon each other, Vogt added.

Further, Vogt said there is no reason to elevate Gregory's Bayesian methods above his own team's statistical techniques. He listed several exoplanet-hunting cases in which, he claimed, Gregory's methodology fell short.

"Gregory's Bayesian Box has a largely unproven and rather checkered record in practice, and therefore has not earned any right to its claim to be the ultimate approach or last word in the exoplanet modeling arena," Vogt said.

The future of Gliese 581g

To date, astronomers have discovered hundreds of alien planets – the last confirmed count was around 520, with 1,235 more candidates announced just this month. But Gliese 581g continues to inspire further research, not all of which casts doubt on the planet's existence.

For example, another researcher, Guillem Anglada-Escude of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, submitted a paper last October supporting the planet's existence. Anglada and a colleague, Harvard's Rebekah Dawson, are working on another paper that suggests 581g and 581f might both be out there, according to Vogt.

The question of Gliese 581g's existence won't be settled definitively until researchers gather more high-precision radial velocity data, Vogt said. But as it stands, he's confident in his team's data, and in the planet's existence.

"Over the past 15 years, our team has discovered and published literally hundreds of planets, with not a single retraction or proven false claim, and we are doing our level best to keep it that way," Vogt said.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.