NASA Programs to Fight Space Junk Threat Under Review

FAIRFAX, Va. – To better meet the growing threat of space junk around Earth, the National Research Council is taking a close look at NASA's orbital debris programs to suggest improvements.

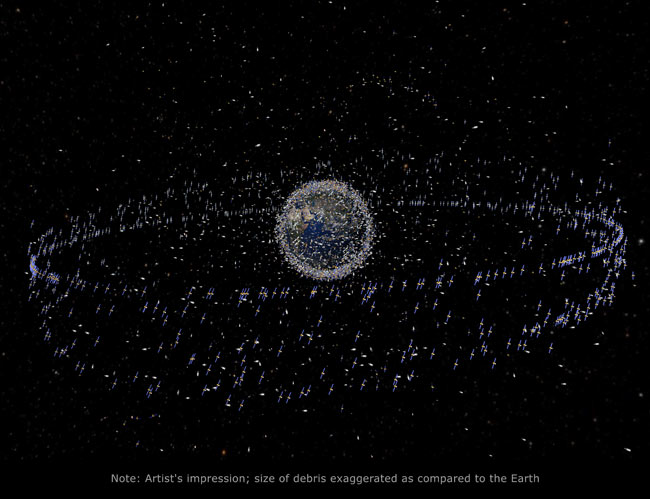

The so-called emptiness of space is in fact far from empty, at least in the neighborhood surrounding Earth, which is becoming more and more crowded with functioning and defunct spacecraft. Naturally occurring small meteoroids, trash such as spent rocket stages, as well as debris created by collisions between satellites, adds to the mess.

The growing detritus poses a danger to all spacecraft orbiting Earth, including manned spaceships like the space shuttle and the International Space Station. So the NRC has established a special committee to review the steps NASA is taking to face the space junk threat.

"It'sa worldwide problem – everybody who does operations in space is creating debris," NASA's Gene Stansbery said Wednesday (March 9) during a committee workshop here to discuss orbital debris programs. Stansbery is the program manager for NASA's Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

The committee is headed by Donald Kessler, a retired NASA scientist famous for conceiving of the Kessler effect – the idea that as the density of objects in space increases, so too do the chances for collisions between them, which only further boosts the amount of junk in space.

Kessler suggested this could cause a cascade of debris, ultimately rendering the corridors of space around Earth unusable by satellites. [Worst Space Debris Events of All Time]

Other members of the committee included scientists, policy experts, satellite industry leaders, and even a former NASA astronaut – Michael Bloomfield.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Currently the Department of Defense's Joint Space Operations Center (JSpOC) tracks more than 20,000 pieces of orbital debris that are larger than 10 centimeters in diameter.

There are probably another half a million objects that are smaller than that, but can still do damage if they impact a spacecraft, said John Lyver, manager of NASA's Meteoroid and Orbital Debris Program Offices at the agency's headquarters in Washington, D.C.

"This is an iceberg. We know what's on this side, where the iceberg is sticking above the water," Kessler said, describing the objects that are being tracked. But we can only guess just how large the threat is in the range where we don't have full data, he added.

So far, most efforts to combat the space debris threat focus on tracking and predicting possible collisions in time for satellites to steer out of the way.

"The orbital debris that is on orbit right now – it is going to stay there," Lyver said. "There is no capability right now to remove objects from orbit, or attempt to change them. We just have to be able to avoid them."

In addition to the technical and scientific challenges, NASA officials told the committee of budget constraints.

"We have insufficient manpower to meet requirements," said William Cooke, program manager of the Meteoroid Environment Office at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. "We're stretched extremely thin."

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.