'Stealth' Solar Eclipse Occurs Friday

If you miss the partial eclipse of the sun on Friday (July 1), don't feel bad; everyone else on the planet will likely miss it, too. But a touch of skywatching trivia makes it a rare event.

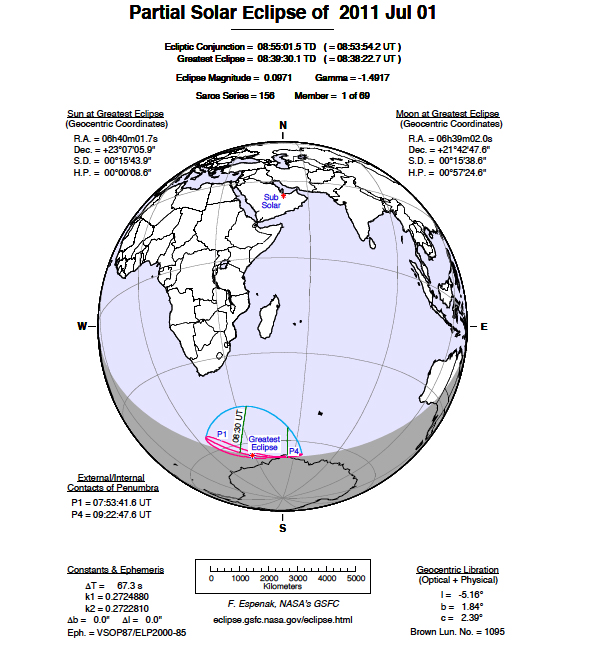

Friday's solar eclipse will occur over an extremely remote part of the world — an uninhabited region in the southern Atlantic Ocean just off the coast of Antarctica. You could even call it a "stealth" eclipse since it will probably only be seen by a few penguins and leopard seals.

"This Southern Hemisphere event is visible from a D-shaped region in the Antarctic Ocean south of Africa," said eclipse expert Fred Espenak, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, on the space agency's Eclipse Web Site. "Such a remote and isolated path means that it may very well turn out to be the solar eclipse that nobody sees."

The 90-minute eclipse will hit its peak at about 4:40 a.m. EDT (0840 UT and GMT). Only 9.7 percent of the sun will be blocked by the moon during the eclipse, making it a minor event as eclipses go. [Photos: "Midnight" Partial Solar Eclipse of 2011]

However, the timing of the solar eclipse lends it some unusual characteristics, making it notable to astronomers. The European Space Agency hopes to use its Proba-2 satellite to observe the event.

First, the July 1 partial solar eclipse is the third of a series of sun and moon eclipses within a single month.

Rare triple eclipse

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On June 1, a more impressive partial solar eclipse occurred over Earth's northern polar region, stunning skywatchers across Europe and Asia. Then, on June 15, a total lunar eclipse (the first of two in 2011) occurred, with the moon turning a blood-red hue for skywatchers across the Eastern Hemisphere.

And now we have a third eclipse, and the second partial eclipse of the sun. This trio of eclipses is possible because of the mechanics of the moon's phases, according to SPACE.com's skywatching columnist Joe Rao. [Infographic: How Moon Phases Work]

Several conditions have to line up for an eclipse to take place. The moon must be in its full or new phases, for example, when it reaches a point in its orbit that intersects with the plane of Earth's orbit, which is called a node, Rao explained earlier this week.

When the moon is near these node points, it can create a solar eclipse (when the moon is between the sun and Earth) or a lunar eclipse (when Earth is between the moon and the sun).

The total lunar eclipse during the full moon on June 15 was extremely closely aligned with its respective node point, which meant that the new moon phases on either side would be in position for a partial solar eclipse, Rao explained.

"Such an unusual circumstance as this won't happen again until 2029," Rao wrote.

A new eclipse series

The other notable feature of Friday's partial solar eclipse is that it kicks off a completely new series of eclipses in what is known as the Saros cycle, astronomers said.

Astronomers have long used the Saros cycle to organize eclipse events because of their predictability. The cycle is 6,585.3 days long (that's 18 years, 11 days, 8 hours) and marks the time between two eclipses with similar geometry in the night sky.

While each Saros cycle lasts just over 18 years, one series of these cycles can last centuries. According to Espenak, each Saros series can last between 1,200 and 1,300 years.

So while Friday's partial solar eclipse will be a less than impressive sight to behold, on the cosmic scale, it is a major turn of the clock.

"This event is the first eclipse of Saros 156," Espenak explained. "The family will produce 8 partial eclipses, followed by 52 annular eclipses and ending with 9 more partials" between 2011 and the year 3237.

You can follow SPACE.com Managing Editor Tariq Malik on Twitter @tariqjmalik. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.