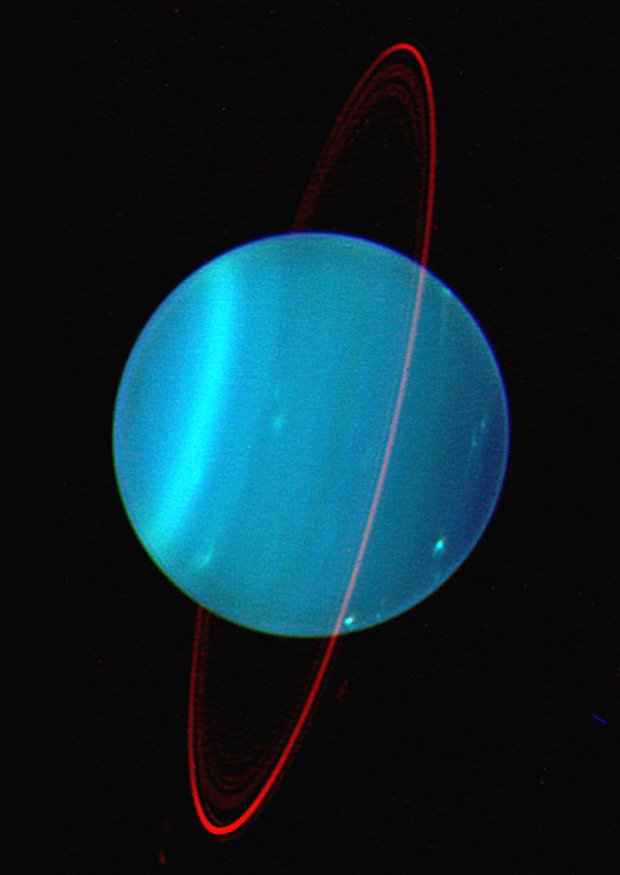

Planet Uranus Got Sideways Tilt From Multiple Impacts

The giant planet Uranus was tipped on its side by a succession of punches rather than a single knockout blow as previously thought, a new study suggests.

The finding sheds light on the early history of Uranus and its many moons. It could also force astronomers to rethink their ideas about how the solar system's giant planets formed and evolved, researchers said.

"The standard planet formation theory assumes that Uranus, Neptune and the cores of Jupiter and Saturn formed by accreting only small objects in the protoplanetary disk," said study leader Alessandro Morbidelli, of the Observatoire de la Cote d’Azur in Nice, France, in a statement. "They should have suffered no giant collisions." [Photos of Uranus, the Tilted Giant Planet]

"The fact that Uranus was hit at least twice suggests that significant impacts were typical in the formation of giant planets," Morbidelli added. "So, the standard theory has to be revised."

An oddball planet

Uranus is a real oddball in our solar system.

Its spin axis is tilted by a whopping 98 degrees, meaning it essentially spins on its side. No other planet has anywhere near such a tilt. Jupiter is tilted by 3 degrees, for example, and Earth by 23 degrees.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists have long suspected that some manner of violent impact knocked Uranus off kilter. The accepted wisdom had been that a single object several times more massive than Earth did the damage, slamming into Uranus long ago, researchers said.

After performing a series of computer simulations, Morbidelli and his team may have found a better explanation.

The research was presented Thursday (Oct. 6) at a joint meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress and the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Science in Nantes, France.

Multiple impacts?

The researchers began by modeling the single-impact scenario. They found that the collision likely occurred in the solar system's very early days, when Uranus was still surrounded by the disk of dust and gas that would eventually form its moons.

After a monstrous collision, the disk would have reformed around Uranus' new, highly skewed equatorial plane. The moons would share Uranus' tilt, which they indeed do.

So far, so good, but then the simulations offered up a surprise, researchers said. If there was just one collision, Uranus' moons would display retrograde motion, orbiting in the opposite direction than that which astronomers observe today.

To account for the discrepancy, the researchers tweaked their simulations' paramaters a bit.

They found that a series of at least two smaller collisions can explain the moons' motions much better than a single giant impact, researchers said. The early solar system thus may have been a more volatile and violent place than previously thought, they added.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.