Milky Way Radiation Reveals Itself to Distant NASA Probes

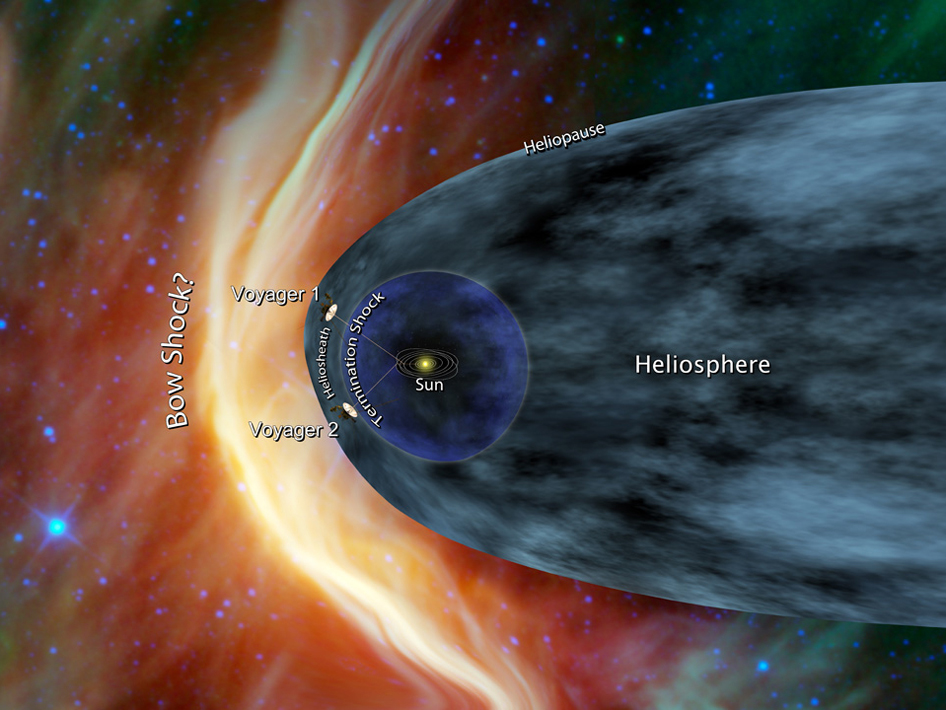

Decades after NASA's Voyager spacecraft began hurtling toward interstellar space, the twin probes are still shedding light on the universe, now by offering an unprecedented view of our own galaxy.

As they roam ever outward to the edge of the solar system, the two Voyager spacecraft are providing the first glimpse of Milky Way radiation that scientists have already seen coming from other galaxies. The data could lead to a better understanding of star formation, including the mystery surrounding the earliest stars in the universe, researchers said.

NASA launched the two Voyager spacecraft in 1977 to explore our solar system's giant planets and to study the electrically charged solar wind streaming from the sun. The probes far exceeded the expectations of mission planners, and to this day, they continue to beam back data.

The Voyagers are now providing us with the first glimpse of a critical type of ultraviolet radiation from our galaxy known as the Lyman-alpha line. This is the brightest band of light shed by hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe.

Studying the Lyman-alpha line can offer many insights into cosmic phenomena, such as star formation, the electrically charged environments in which the atmospheres of young planets evolve, and the shocked gas in interstellar space. [Photos from NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 Probes]

Astronomers have seen Lyman-alpha rays from other galaxies, helping them peer into the universe's early history. However, we have never seen ones from our own galaxy, because our sun essentially blinds our view.

Specifically, ultraviolet rays from our sun get scattered around by hydrogen entering our solar system from interstellar space. This leads to a haze that blinds us to Lyman-alpha rays from elsewhere in our galaxy. We can detect other galaxies' Lyman-alpha rays because they have shifted into longer optical and infrared wavelengths — ones that no longer get scattered by this hydrogen — as their galaxies rush away from us. This is similar to how ambulance sirens grow lower in pitch as the vehicle drives farther away.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now Voyager 1 and 2 are far enough away from this ultraviolet haze for them to get a clear view of the Milky Way's Lyman-alpha rays.

"It is like beginning to see small candles within a brightly lit room," study lead author Rosine Lallement, a space scientist and astronomer at the Paris Observatory in Meudon, France, told SPACE.com.

The spacecraft have confirmed that most of these newfound rays appear to come from star-forming regions, as astronomers expected. Future study of the Milky Way's Lyman-alpha rays could help us better understand those from other galaxies, researchers added.

"This radiation traces where young hot stars are being born — therefore, knowing the amount of emitted Lyman-alpha radiation from a galaxy corresponds to the rate at which stars are being born," Lallement said. "A major goal is to detect the first apparition of stars in the young universe, so detecting Lyman-alpha from the most-distant ones and correctly interpreting the signal is one of the major challenges."

Ironically, just as the Voyager probes are getting their best views of these Milky Way rays, their ability to see them is failing. Due to lack of power, the ultraviolet spectrometer on Voyager 2 has been switched off, and that same instrument on Voyager 1 could get turned off soon as well.

Still, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, which is currently on its way to Pluto, might soon be able to monitor these rays as well.

Lallement and her colleagues detailed their findings online in the Dec. 1 issue of the journal Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us