This year's second total lunar eclipse on Saturday (Dec. 10) will offer a rare chance to see a strange celestial sight traditionally thought impossible.

Ringside seats for the lunar eclipse can be found in Alaska, Hawaii, northwestern Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and central and eastern Asia. Over the contiguous United States and Canada, the eastern zones will see either only the initial penumbral stages before moonset, or nothing at all.

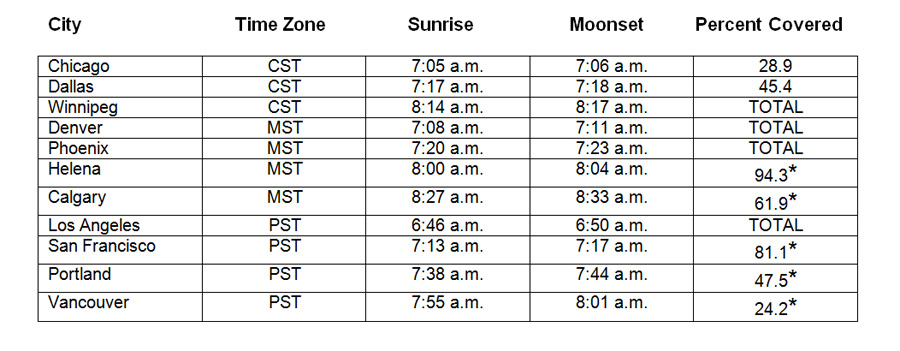

Over the central regions of the United States, the moon will set as it becomes progressively immersed in the Earth's umbral shadow. The Rocky Mountain states and the prairie provinces will see the moon set in total eclipse, while out west the moon will start to emerge from the shadow as it sets.

The moon passes through the southern part of the Earth's shadow, with totality beginning at 6:06 a.m. PST and lasting 51 minutes. [Total Eclipse of the Moon (Infographic)]

For most places in the United States and Canada, there will be a chance to observe an unusual effect, one that celestial geometry seems to dictate can't happen. The little-used name for this effect is a "selenelion" (or "selenehelion") and occurs when both the sun and the eclipsed moon can be seen at the same time.

Seeing the impossible

But wait! How is this possible? When we have a lunar eclipse, the sun, Earth and moon are in a geometrically straight line in space, with the Earth in the middle. So if the sun is above the horizon, the moon must be below the horizon and completely out of sight (or vice versa).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And indeed, during a lunar eclipse, the sun and moon are exactly 180 degrees apart in the sky; so in a perfect alignment like this (a "syzygy") such an observation would seem impossible.

But it is atmospheric refraction that makes a selenelion possible.

Atmospheric refraction causes astronomical objects to appear higher in the sky than they are in reality.

For example: when you see the sun sitting on the horizon, it is not there really. It's actually below the edge of the horizon, but our atmosphere acts like a lens and bends the sun's image just above the horizon, allowing us to see it.

This effect actually lengthens the amount of daylight for several minutes or more each day; we end up seeing the sun for a few minutes in the morning before it has actually risen and for a few extra minutes in the evening after it actually already has set.

The same holds true with the moon, as well.

As a consequence of this atmospheric trick, for many localities there will be an unusual chance to observe a senelion firsthand with Saturday morning's shadowy event. There will be a short window of roughly 1-to-6 minutes (depending on your location) when you may be able to simultaneously spot the sun rising in the east-southeast and the eclipsed full moon setting in the west-northwest.

Regions of visibility

For places to the east of the Appalachian Range, this will, unfortunately, be a non-event. Although the moon will still be above the horizon when it begins to enter the Earth's shadow at 6:33 a.m. EST, it initially is the penumbral shadow that first contacts the moon.

This shadow is so faint that at least three-quarters of the moon's diameter must be immersed within it before you would have a chance of detecting it visually, either with your naked eyes or using an optical aid. That means, if you live in places such as Boston, New York or Miami, the moon will look perfectly normal as it sets.

But from southeast Ontario, through the Ohio Valley and continuing south to the central Gulf Coast, the upper-left portion of the moon will begin appearing somewhat darker or "smudged" as it begins to disappear beyond the horizon. As you head farther west, the moon's entry into the much-darker part of the Earth's shadow (the umbra) will become evident at 7:45 a.m. Eastern Time or 6:45 a.m. Central.

Across portions of the Upper Midwest, the Nation's Heartland, down into the central parts of Oklahoma and Texas, about half of the setting moon will be immersed in the umbra. The shadow will appear to be creeping almost straight down across the moon's face from its upper limb.

Across the Central and Southern Plains only the lowermost portion of the moon will remain in view as it moves down below the west-southwest horizon. Farther west and north, across the Desert Southwest and High Plains, the moon will rise completely immersed in the Earth's shadow, while for parts of the Intermountain Region, Northern California and the Pacific Northwest, the moon will begin to emerge from the umbra as it sets.

Important facts to consider

In order to observe the selenelion, you should make sure that both your east-southeast and west-northwest horizons are free of any tall obstructions that might block your views of the setting moon or rising sun.

Also, keep in mind that, depending on the clarity of your sky, you might actually lose sight of the moon about 10 or 15 minutes before sunrise thanks to the brightening morning twilight and the moon sinking into any horizon haze (atmospheric "schmutz").

Keep in mind that this holds only for the uneclipsed portion of the moon. Indeed, if the moon is totally eclipsed at moonset, you will probably have to scan the western horizon as the twilight increases in order to detect the moon, which will perhaps resemble a dim and eerily illuminated softball.

Editor's Note: If you take a photo or video of the eclipse that you'd like to share with SPACE.com for a possible story or gallery, please email Tariq Malik at tmalik@space.com or Clara Moskowitz at cmoskowitz@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.