This story was updated at 2:40 EST.

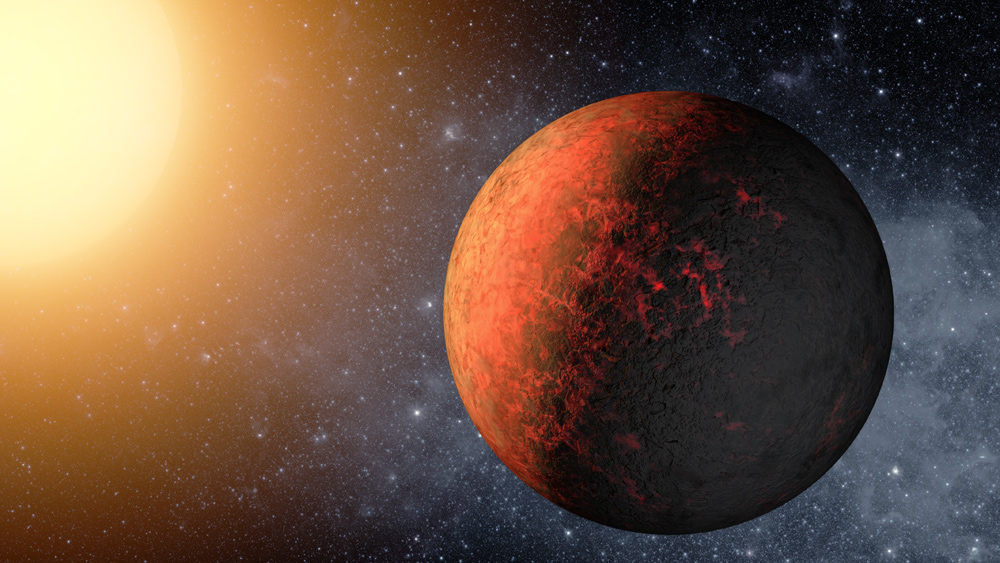

Astronomers on Tuesday (Dec. 20) announced the discovery of the first two Earth-size alien planets — a historic find for sure, but the newfound worlds didn't exactly receive historic names.

The two alien planets are officially known as Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f, a nod to the instrument that detected them, NASA's prolific Kepler space telescope. The planets' host star is Kepler-20, and the letters indicate that 20e was the fourth planet discovered in this alien solar system and 20f the fifth. (By convention, the first planet found in a system is always designated "b," not "a.")

All of this is standard exoplanet-naming procedure — star name plus letter. But the Kepler mission isn't the only planet-hunting project working today, and the others choose their star appellations differently. So there are also alien worlds out there with names like HD 171028 b and MOA-2007-BLG-192-L b.

Such monikers don't roll trippingly off the tongue or lodge firmly in most folks' memory. So it may be time to think about a nomenclatural shake-up, some researchers say, to make alien worlds' names more consistent — and to help make exoplanet science more accessible to the public as well. [Gallery: The Smallest Alien Planets]

"There's no way the public should have to remember these names," said Francois Fressin of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, lead author of the study announcing the discovery of Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f. "I'm working like 15 hours a day on Kepler, and I'm not sure I could tell you which one is each of the Kepler planets."

Exoplanet researchers could work together to develop a coherent naming system, one with consistent rules or guidelines, Fressin suggested. As an example of such a system, he pointed to the planets of our own solar system, all of which except Earth are named for Greek or Roman gods.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If we start doing that with more accessible names, it would be a plus," Fressin told SPACE.com. "So I really encourage those kinds of discussions."

Kepler team member Dave Charbonneau, Fressin's colleague at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and a co-discoverer of Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f, voiced similar sentiments.

"Sadly, we do just use the boring nomenclature of starname + letter. We really need to fix this!" Charbonneau told SPACE.com via email. "I have three daughters, and the oldest is just starting kindergarten. We need engaging names for the benefit of schoolchildren everywhere."

Public engagement could also come in more active ways, suggested veteran planet hunter and Kepler scientist Geoff Marcy of the University of California, Berkeley.

"We need SPACE.com to hold a naming contest!" Marcy wrote in an email to SPACE.com.

We were thinking along similar lines. After the announcement of Kepler-20e and Kepler-20f, SPACE.com asked readers on Facebook to vote for their favorite names for the Earth-size planets. The winning monikers? Romulus and Remus, which "Star Trek" fans will recognize as the names of the twin homeworlds for the fictional Romulan alien race.

You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.