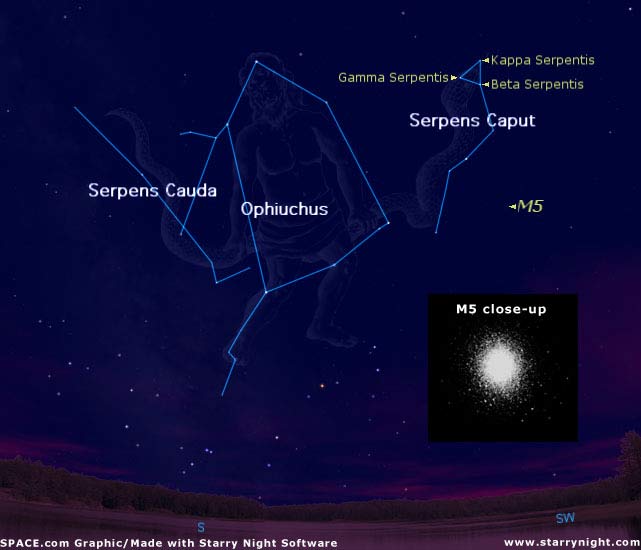

During the early evening hours, we can gaze toward the south and see the "celestial medicine man" Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer, a star pattern that is teamed with the constellation Serpens.

Serpens, the Snake is the only constellation that's cut in two. The head of the Serpent lies west of the giant constellation Ophiuchus and is known as Serpens Caput; while to the east of Ophiuchus lies smaller Serpens Cauda, the tail.

To the naked eye, four stars brighter than magnitude 4.5 mark the head of Serpens. The three brightest, Beta, Gamma and Kappa Serpentis are set in a nearly equilateral triangle. Off to the south of the Serpent's head is the location of Messier 5, one of the sky's finest globular clusters with a much-compressed center, appearing roughly half the apparent diameter of the full Moon. Believed to contain over a half million stars, M5 can be seen without optical aid as a fuzzy "star" on a very dark, clear night.

Small binoculars show a tiny fuzz ball. Giant binoculars (10x70s and up) show the cluster rapidly brightening toward the center with perhaps the slightest hint of a mottled texture.

King James I of England, who reigned in the 1600's, once referred to Ophiuchus as "a mediciner after made a god," because the Serpent Bearer was often identified with Aesculapius, who, in Greek mythology, was originally a mortal physician who never lost a patient by death. This alarmed Hades, god of the dead, who prevailed on his brother, Zeus, to liquidate Aesculapius. In recognition of his merits, however, Aesculapius was put into the sky as a constellation. The association with a serpent may have come from the belief that, by shedding its skin, it is rejuvenated. And to this day, the symbol of the medical profession is the caduceus insignia of our Army's Medical Corps, which is a winged staff with serpents twined around it.

The constellation's odd name of Ophiuchus derives from the Greek root ophis (serpent) and cheiro-o (to handle). As for Hygeia and Panacea, they were Aesculapius's daughters. Although not represented in the sky, like their father, both have long been patron saints to modern-day physicians.

Interestingly, during late autumn the Sun, moving along the ecliptic, will be in Ophiuchus for 19 days. It enters Scorpius on November 23, leaves a week later for Ophiuchus on November 30 and enters Sagittarius on December 18. Thus, the Sun is in Ophiuchus more than twice as long as in Scorpius, an "official" zodiacal constellation. Astrologers on the other hand do not recognize Ophiuchus as one of the traditional houses of the Sun.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The International Astronomical Union all officially approves the constellations shown on modern star atlases, but while constellations are official, asterisms are not. An asterism is often defined as a noteworthy or striking pattern of stars within a constellation, but that is not always the case. In addition, many old star charts show constellations that fell out of favor with astronomers and failed to make the list of 88 that have been recognized since 1930.

One such pattern is just off of the shoulder of Ophiuchus. It is Taurus Poniatovii, or Poniatowski's Bull. It was created in 1777 by the Abb? Martin Poczobut, director of the Royal Observatory of Vilna in honor of King Stanislaus Poniatowski of Poland. This is a V-shaped pattern of five stars ranging from magnitude 3.9 to 5.7 and its likeness to the V-shaped Hyades group forming the face of winter constellation Taurus probably inspired Poczobut to place this bull in the summer sky.

If Taurus Poniatovii were still recognized as a constellation, it would have the distinction of containing the star with the largest known apparent motion ("proper motion") in our sky. Barnard's Star is a 9.5-magnitude red dwarf that is named after Edward Emerson Barnard (1857-1923), one of those legendary telescopic observers of an era long gone.

It was Barnard, who in 1916 spotted its rapid motion during a comparison of photographic plates of the Milky Way made in 1894 and 1916. Now called Barnard's "Runaway Star," it has a mass computed to be just 16 percent that of the Sun and a luminosity only 1/2500 that of the Sun. It's the next closest star to us after the Alpha Centauri system, at 5.9 light years; its actual velocity is about 103 miles per second and its proximity plus high space velocity combine to give it a proper motion of 10.31 seconds of arc each year.

Put into layman's terms, from our Earthly vantagepoint, this carries it across the sky at roughly the apparent width of the full Moon in less than 180 years.

Basic Sky Guides

- Full Moon Fever

- Astrophotography 101

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- 10 Steps to Rewarding Stargazing

- Understanding the Ecliptic and the Zodiac

- False Dawn: All about the Zodiacal Light

- Reading Weather in the Sun, Moon and Stars

- How and Why the Night Sky Changes with the Seasons

- Night Sky Main Page: More Skywatching News & Features

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.