There are 88 officially recognized constellations in the sky, and these astronomical patterns have a fascinating and long history.

Forty-eight of the constellations are known as ancient or original, meaning they were talked about by the Greeks and probably by the Babylonians and still earlier peoples. After the 15th century, with the age of the great discoveries and worldwide navigation, the southernmost parts of the sky became known to man and had to be charted.

Furthermore, across the entire sky were large gaps filled chiefly with dim stars between them. In more recent times people have invented the modern constellations to fill up some of these spaces.

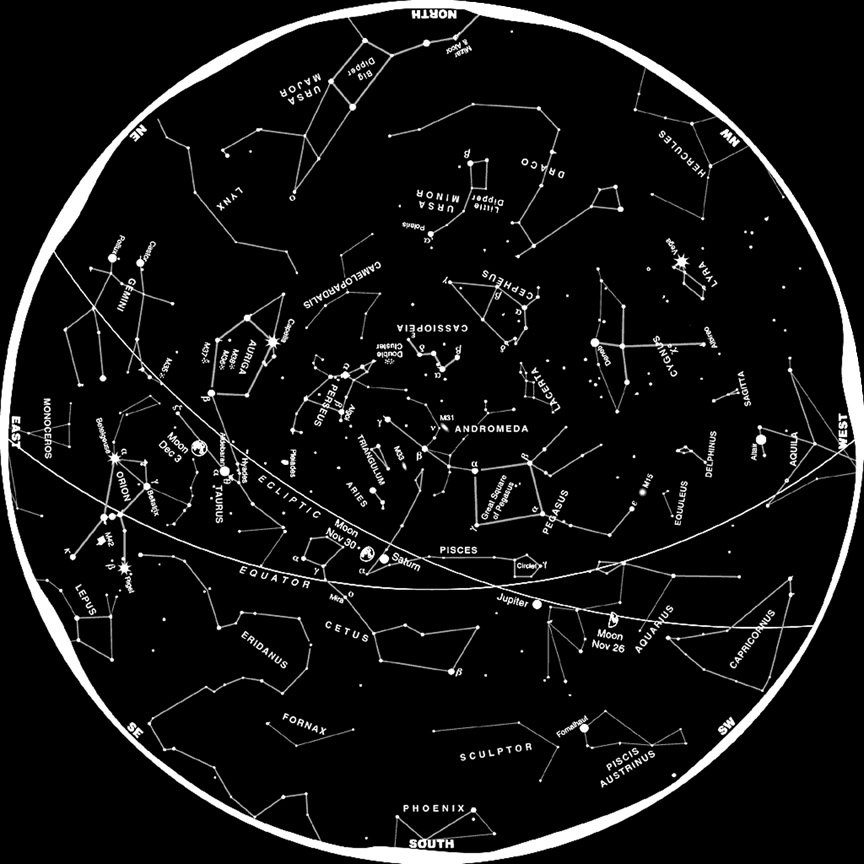

In our current evening sky, roughly between the bright star Capella and the Big Dipper’s bowl are two examples of modern constellations. The first is the “camel-leopard,” Camelopardalis, which in Latin means giraffe.

The other is the Lynx, one of only two animal constellations with identical Latin and English names (the other is Phoenix). This celestial feline is rather dim and hard to visualize. Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687) a 17th century Renaissance man placed it in the sky.

Aside from being an astronomer, Hevelius was an artist, engraver, well-to-do man of affairs and a leading citizen of Danzig, Poland. Interestingly, the old astronomy books and sky charts, which depicted the constellations as allegorical drawings, placed the lucida (brightest star) of Lynx in the tuft of its tail. From these drawings it would seem that nearby Leo Minor, the Smaller Lion, is about to provoke a cat fight by biting Lynx’s tail!

Although the telescope was just coming into general use during Hevelius’ time, he openly rejected the new invention. In his star atlas of 1690, he actually tucked a cartoon into the corner of one sky chart showing a cherub holding a card with the Latin motto “The naked eye is best.”

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In creating Lynx, Hevelius chose a cat-like animal that possesses excellent eyesight. Lynx itself is a region chiefly devoid of bright stars, and Hevelius openly admitted that you would have to have the eyes of a lynx to see it.

Another faint star pattern now no longer recognized is Felis, the Cat, which was the creation of an 18th century Frenchman, Joseph Jerome Le Francais de Lalande (1732-1807).

“I am very fond of cats," he said, explaining his choice. "I will let this figure scratch on the chart. The starry sky has worried me quite enough in my life, so that now I can have my joke with it.”

Although this celestial feline does not exist today, cat fanciers will be consoled by the fact that there are three other members of the cat family — Leo (the Lion), Leo Minor (the Smaller Lion) and Lynx — that are well situated and close together in our current evening sky.

I’ve always wondered if Felis might have later inspired New Jersey cartoonist Otto Messmer to create a curious, mischievous and inventive little character known as Felix, the Cat.

Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (1713-1762) is considered a pioneer in astronomy. Between 1751 and 1753, this modest, but hardworking French astronomer was stationed at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, where he catalogued the positions of 9,766 southern stars in just 11 months.

He is perhaps best remembered today, however, for inventing 14 constellations that he added to the southern sky. Although they are all still officially recognized today, they are composed mostly of very faint stars, which formed patterns that generally are dim and pointless. Unlike many of the larger, brighter constellations, which were chiefly based on mythology and legend, Lacaille chose to honor inanimate objects.

One of these is in our current evening sky: Antlia Pneumatica, the Air Pump, which was created by Lacaille around the year 1750. Despite being composed chiefly of dim, faint stars, it is still officially recognized to this day as a constellation, though its name has since been shortened simply to Antlia, the Pump.

Just above the Pump was Felis, the Cat, which is no longer recognized.

Lacaille’s other constellations included a Sculptor’s Chisels (Caela Sculptoris), The Compasses (Circinus), a Chemical Furnace (Fornax Chemica), a Pendulum Clock (Horologium), a Carpenter’s Square (Norma), Hadley’s Octant (Octans Hadleianus), a Painter’s Easel (Equuleus Pictoris), a Mariner’s Compass (Pyxis Nautica), a Rhomboidal Net (Reticulum Rhomboidalis), a Sculptor’s Workshop (Apparatus Sculptoris), a Microscope (Microscopium), a Telescope (Telescopium) and lastly, Table Mountain (Mons Mensae), which overlooked Lacaille’s observatory.

Is it little wonder that when Heber D. Curtis (1872-1942), director of the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh, Penn., saw a chart depicting all of Lacaille’s creations he exclaimed: “It looks like somebody’s attic!”

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.