Early Universe's Dark Galaxies May Have Been Revealed for 1st Time

A telescope in South America has found tantalizing evidence of primitive galaxies born in the early universe, a find that, if confirmed, would mark the first-ever view of the so-called "dark galaxies."

Dark galaxies are small, gas-rich objects from the early universe. The existence of such galaxies, which are devoid of stars, but packed with gas, has long been predicted in galaxy formation theories, but direct proof of them has so far remained elusive.

Now, an international team of astronomers may have found dark galaxies by using the light from quasars, the brightest and most energetic objects in the universe, as a guide.

Quasars are powered by enormous black holes that give off huge amounts of energy and light as gas, dust and other material falls into their cores. The astronomers pinpointed the dark galaxies by their glow from the quasars' light.

"Our approach to the problem of detecting a dark galaxy was simply to shine a bright light on it," study co-author Simon Lilly, of ETH Zurich, an engineering and science university in Switzerland, said in a statement. "We searched for the fluorescent glow of the gas in dark galaxies when they are illuminated by the ultraviolet light from a nearby and very bright quasar. The light from the quasar makes the dark galaxies light up in a process similar to how white clothes are illuminated by ultraviolet lamps in a night club."

The quasar key

In the new study, the scientists were able to glean some preliminary characteristics of the dark galaxies. They estimate that the mass of the gas in such galaxies is roughly 1 billion times that of the sun, which is expected for gas-rich, low-mass galaxies in the early universe. [7 Surprising Things About the Universe]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The astronomers also estimate that star formation in the dark galaxies is suppressed by a factor of more than 100 compared with typical star-forming galaxies at similar stages in their cosmic histories.

In theories of galaxy formation, dark galaxies are thought to be the building blocks of the bright, star-filled galaxies we see today. Some theories state that dark galaxies may have also funneled gas to larger galaxies to form the stars that currently exist.

But dark galaxies are inherently challenging to spot, the researchers said. Since dark galaxies have no stars, they do not emit much light. Astronomers have long attempted to confirm their existence using new techniques that could reveal dark galaxies in the cosmos.

Previous studies of small absorption dips in the spectra of background light sources were thought to have hinted at dark galaxies, but this new study may be the first time that these mysterious objects have been directly detected.

Chasing dark galaxies

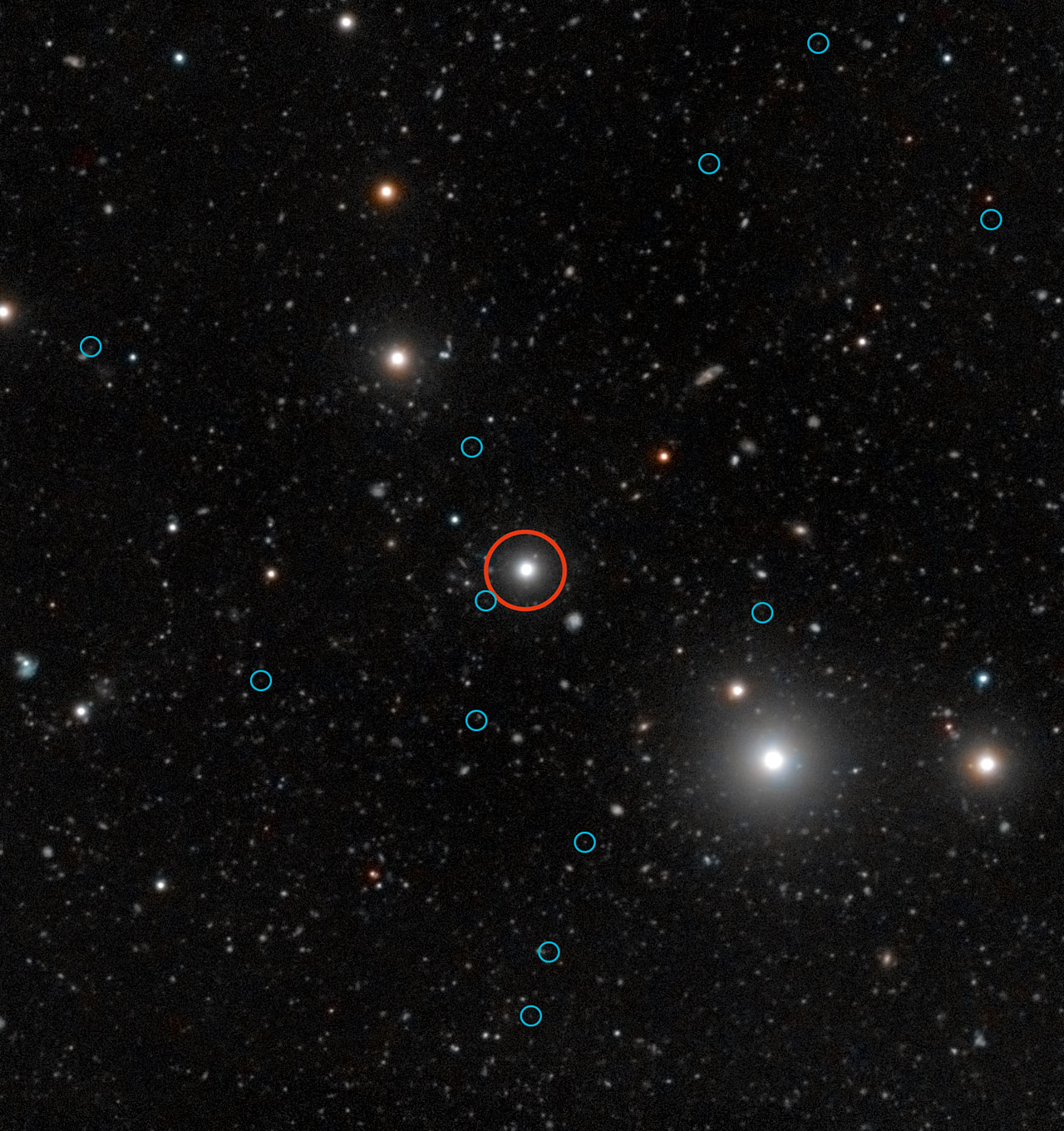

Using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in northern Chile, the researchers saw the extremely faint fluorescent glow of the dark galaxies. They used the telescope's FORS2 instrument to map a region of the sky around the bright quasar HE 0109-3518, searching for ultraviolet light that is released by hydrogen gas when it is bombarded with intense radiation.

"After several years of attempts to detect fluorescent emission from dark galaxies, our results demonstrate the potential of our method to discover and study these fascinating and previously invisible objects," study lead author Sebastiano Cantalupo, from the University of California, Santa Cruz, said in a statement.

The astronomers found almost 100 gaseous objects within a few million light-years of the brilliant quasar. They eventually narrowed the list to 12, after weeding out objects where the emission might be a product of star formation in the galaxies, rather than from the quasar's light.

According to the researchers, these objects represent the most convincing detections of dark galaxies in the early universe to date.

"Our observations with the VLT have provided evidence for the existence of compact and isolated dark clouds," Cantalupo said. "With this study, we've made a crucial step towards revealing and understanding the obscure early stages of galaxy formation and how galaxies acquired their gas."

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.