The 9 most brilliant comets ever seen

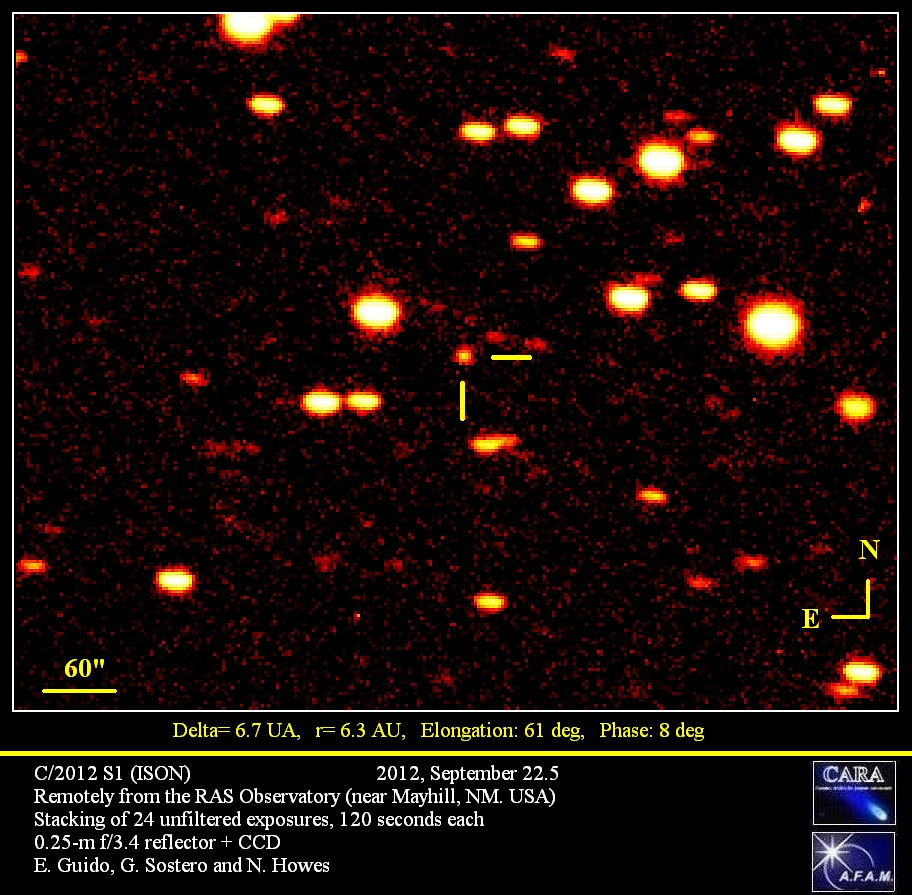

Excitement is riding high in the astronomical community with the recent discovery of Comet ISON, which is destined to pass exceedingly close to the sun in late November 2013 and might possibly become dazzlingly bright.

The latest information issued by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory suggests that this comet could get as bright as magnitude -11.6 on the astronomers' brightness scale; that's as bright as nearly full moon! That would also be bright enough for Comet ISON to be visible during the daytime.

Comets that are visible to the naked eye during the daytime are rare, but such cases are not unique. In the last 332 years, it has happened only nine other times. Here is a listing of past comets that have achieved this amazing feat.

In this list we quote the brightness of the comets in terms of magnitude. On this scale, larger numbers represent dimmer objects; the brightest stars are generally zero to first magnitude, while super-bright objects such as Venus and the moon achieve negative magnitudes. [Spectacular Comet Photos (Gallery)]

Great Comet of 1680

This comet has an orbit strikingly similar to Comet ISON, begging the question of whether both objects are one and the same or at the very least are somehow related. Discovered on Nov. 14, 1680 by German astronomer Gottfried Kirsch, this was the first telescopic comet discovery in history. By Dec. 4, the comet was visible at magnitude +2 with a tail 15 degrees long. On Dec. 18 it arrived at perihelion — its closest approach to the sun — at a distance of 744,000 miles (1.2 million kilometers).

A report from Albany, N.Y. indicated that it could be glimpsed in daylight passing above the sun. In late December, it reappeared in the western evening sky, again of magnitude +2, and displaying a long tail that resembled a narrow beam of light that stretched for at least 70 degrees. The comet faded from naked-eye visibility by early February 1681.

Great Comet of 1744

First sighted on Nov. 29, 1743 as a dim 4th-magnitude object, this comet brightened rapidly as it approached the sun. Many textbooks often cite Philippe Loys de Cheseaux, of Lausanne, Switzerland as the discoverer, although his first sighting did not come until two weeks later. By mid-January 1744, the comet was described as 1st-magnitude with a 7-degree tail.

By Feb. 1 it rivaled the star Sirius in brightness and displayed a curved tail 15 degrees in length. By Feb. 18 the comet was as bright as Venus and now displayed two tails. On Feb. 27, it peaked at magnitude -7 and was reported visible in the daytime, 12 degrees from the sun. Perihelion came on March 1, at a distance of 20.5 million miles (33 million km) from the sun. On March 6, the comet appeared in the morning sky, accompanied by six brilliant tails that resembled a Japanese hand fan.

Great Comet of 1843

This comet was a member of the Kruetz Sungrazing Comet Group, which has produced some of the most brilliant comets in recorded history. Such comets actually graze through the outer atmosphere of the sun, and often do not survive.

The 1843 comet passed only 126,000 miles (203,000 km) from the sun's photosphere on Feb 27, 1843. Although a few observations suggest that it was seen for a few weeks prior to this date, on the day when of its closest approach to the sun it was widely observed in full daylight. Positioned only 1 degree from the sun, this comet appeared as "an elongated white cloud" possessing a brilliant nucleus and a tail about 1 degree in length. Passengers onboard the ship Owen Glendower, off the Cape of Good Hope described it as a "short, dagger-like object" that closely followed the sun toward the western horizon.

In the days that followed, as the comet moved away from the sun, it diminished in brightness but its tail grew enormously, eventually attaining a length of 200 million miles (320 million km). If you were able to place the head of this comet at the sun's position, the tail would have extended beyond the orbit of the planet Mars!

Great September Comet of 1882

This comet is perhaps the brightest comet that has ever been seen; a gigantic member of the Kreutz Sungrazing Group. First spotted as a bright zero-magnitude object by a group of Italian sailors in the Southern Hemisphere on Sept.1, this comet brightened dramatically as it approached its rendezvous with the sun.

By Sept. 14, it became visible in broad daylight and when it arrived at perihelion on the 17th, it passed at a distance of only 264,000 miles (425,000 km) from the sun's surface. On that day, some observers described the comet's silvery radiance as scarcely fainter than the limb of the sun, suggesting a magnitude somewhere between -15 and -20!

The following day, observers in Cordoba, Spain described the comet as a "blazing star" near the sun. The nucleus also broke into at least four separate parts. In the days and weeks that followed, the comet became visible in the morning sky as an immense object sporting a brilliant tail. Today, some comet historians consider it as a "Super Comet," far above the run of even Great Comets.

Great January Comet of 1910

The first people to see this comet — then already at first magnitude — were workmen at the Transvaal Premier Diamond Mine in South Africa on Jan. 13, 1910. Two days later, three men at a railway station in nearby Kopjes casually watched the object for 20 minutes before sunrise, assuming that it was Halley's Comet.

Later that morning, the editor of the local Johannesburg newspaper telephoned the Transvaal Observatory for a comment. The observatory's director, Robert Innes, must have initially thought this sighting was a mistake, since Halley's Comet was not in that part of the sky and nowhere near as conspicuous. Innes looked for the comet the following morning, but clouds thwarted his view. However, on the morning of Jan. 17, he and an assistant saw the comet, shining sedately on the horizon just above where the sun was about to rise. Later, at midday, Innes viewed it as a snowy-white object, brighter than Venus, several degrees from the sun. He sent out a telegram alerting the world to expect "Drake's Comet" — for so "Great Comet" sounded to the telegraph operator.

It was visible during the daytime for a couple more days, then moved northward and away from the sun, becoming a stupendous object in the evening sky for the rest of January in the Northern Hemisphere. Ironically, many people in 1910 who thought they had seen Halley's Comet instead likely saw the Great January Comet that appeared about three months before Halley. [Photos of Halley's Comet Through History]

Comet Skjellerup-Maristanny, 1927

Another brilliant comet, first seen as a 3rd magnitude object in early December 1927, had the unfortunate distinction of arriving under the poorest observing circumstances possible. The orbital geometry was such that the approaching comet could not be seen in a dark sky at any time from either the Northern or the Southern Hemisphere.

Nonetheless, the comet reached tremendous magnitude at perihelion on Dec. 18. Located at a distance of 16.7 million miles (26.9 million km) from the sun, it was visible in daylight about 5 degrees from the sun at a magnitude of -6. As the comet moved out of the twilight and headed south into darker skies, it faded rapidly, but still threw off an impressively long tail that reached up to 40 degrees in length by the end of the month.

Comet Ikeya-Seki, 1965

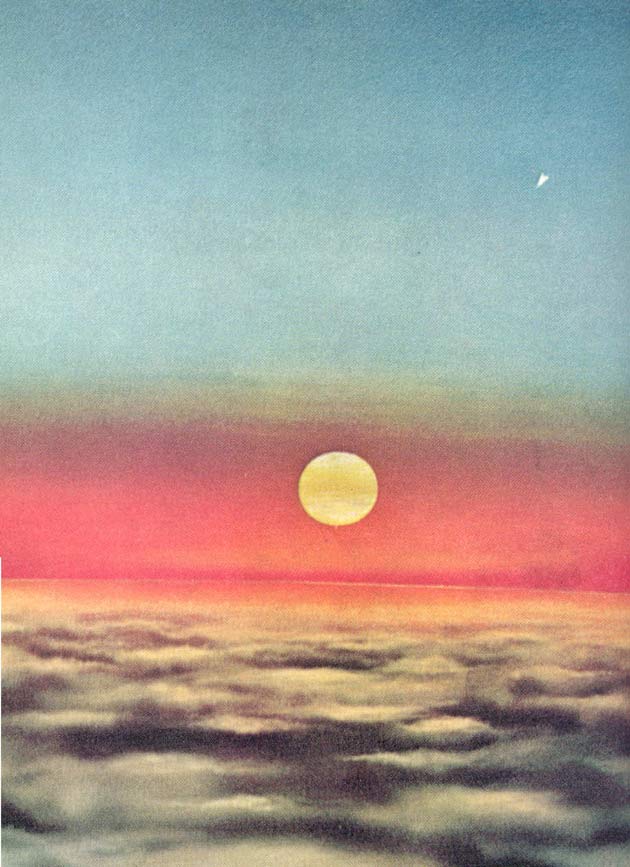

This was the brightest comet of the 20th century, and was found just over a month before it made perihelion passage in the morning sky, moving rapidly toward the sun.

Like the Great Comets of 1843 and 1882, Ikeya-Seki was a Kreutz Sungrazer, and on Oct. 21, 1965, it swept within 744,000 miles (1.2 million km) of the center of the sun. The comet was then visible as a brilliant object within a degree or two of the sun, and wherever the sky was clear, the comet could be seen by observers merely by blocking out the sun with their hands.

From Japan, the homeland of the observers who discovered it, Ikeya-Seki was described as appearing "ten times brighter than the full moon," corresponding to a magnitude of -15. Also at that time, the comet's nucleus was observed to break into two or three pieces. Thereafter, the comet moved away in full retreat from the sun, its head fading very rapidly but its slender, twisted tail reaching out into space for up to 75 million miles (120 million km), and dominating the eastern morning sky right on through the month of November.

Comet West, 1976

This comet developed into a beautiful object in the morning sky of early March 1976 for Northern Hemisphere observers. It was discovered in November 1975 by Danish astronomer Richard West in photographs taken at the European Southern Observatory in Chile. Seventeen hours after passing within 18.3 million miles (29.5 million km) of the sun on Feb. 25, 1976, it was glimpsed with the naked eye 10 minutes before sunset by John Bortle.

In the days that followed, Comet West displayed a brilliant head and a long, strongly structured tail that resembled "a fantastic fountain of light." Sadly, having been "burned" by the poor performance of Comet Kohoutek two years earlier, the mainstream media all but ignored Comet West, so most people unfortunately failed to see its dazzling performance.

Comet McNaught, 2007

Discovered in August 2006 by astronomer Robert McNaught at Australia's Siding Spring Observatory, this comet evolved into a brilliant object as it swept past the sun on Jan. 12, 2007 at a distance of just 15.9 million miles (25.6 million km). According to reports received from a worldwide audience at the International Comet Quarterly, it appears that the comet reached peak brightness on Sunday, Jan. 14 at around 12 hours UT (7:00 a.m. EST, or 1200 GMT). At that time, the comet was shining at magnitude 5.1.

Some observers, such as Steve O'Meara, located at Volcano, Hawaii, observed McNaught in daylight and estimated a magnitude as high as -6, noting, "The comet appeared much brighter than Venus!"

After passing the sun, Comet McNaught developed a stupendously large, fan-shaped tail somewhat reminiscent of the Great Comet of 1744. Unfortunately for Northern Hemisphere observers, the best views of Comet McNaught were mainly from south of the equator.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.