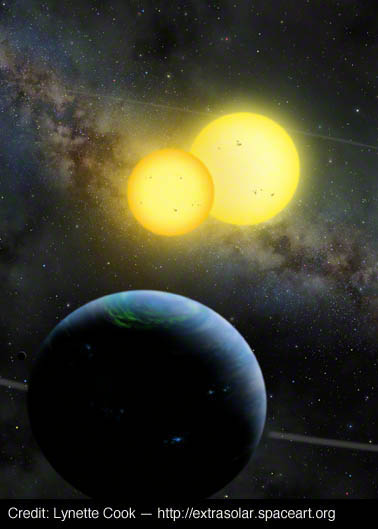

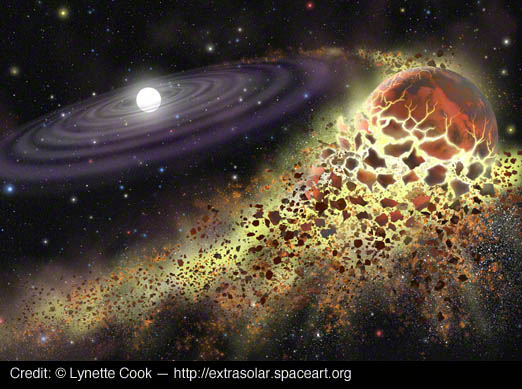

If you've read a few news stories about alien planets over the last decade and a half, you're probably familiar with Lynette Cook's work.

Cook has been illustrating newfound exoplanets since 1995, when she drew 51 Pegasi b, the first alien world ever discovered around a sun-like star. Since then, she has illustrated many other famous extrasolar planets, including the double-sun "Tatooine" world Kepler-35b and Gliese 581g, which may be capable of supporting Earth-like life if the planet exists (some astronomers remain unconvinced).

SPACE.com caught up with Cook recently to discuss how she goes about drawing alien planets, and how her illustrations can contribute to humanity's understanding of these far-flung and fascinating worlds.

SPACE.com: How do you envision what exoplanets might look like?

Lynette Cook: I have to know the type of star — for example, is it sun-like, or is it a red dwarf? I have to know the distance between the star and the planet, because that's going to tell me if it's really hot, if it's in the habitable zone or if it's very distant and very cold. And then I have to know the mass of the planet as well, because that will tell me, is it gaseous or is it rocky? [Gallery: Lynette Cook's Exoplanet Art]

All of those parameters have to go together. And then one can decide other things — like, if it's in the habitable zone and it's rocky, do I want to show that there could be water? If it's at the inner edge of the habitable zone, it might have water, but it's not likely to have any ice or any polar caps. If it's at the outer edge, it could have liquid water and frozen water both, which is kind of neat. If it's something that's very close in, then it would be very hot and could look molten.

SPACE.com: Do you have pretty free rein when it comes to imagining these worlds, or do other people have a significant say?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cook: It's usually a combination. Sometimes the person I work with will suggest something, especially if it's a discoverer. He might say, "OK, this is going to be for a press release. I don't want to go too far out on a limb here, so we're going to show the planet only and no moons, because we don't know for sure that moons are there."

If it's something that maybe is for Astronomy magazine or Sky and Telescope, then maybe the moons are OK. So it's going to be somewhat determined by what the end use is for a specific piece of art.

SPACE.com: What's the illustration process like, from start to finish?

Cook: It really is a lengthy process, especially when it is tailored to science, the actual science. Because when a job comes in, or even if I initiate it and want to collaborate — say, with [planet-hunter] Geoff Marcy or someone else — then there's initially a discussion period: Hey, I'm going to do this planet, this system; these are the characteristics, and what can we show?

And then I do rough sketches, then we go over that, I make changes, and there could be several stages of roughs before the final rough — the one that seems to have all of the necessary and correct components — is ready to go to final art. [How Planets in Alien Solar Systems Stack Up (Infographic)]

And then I'll do the final art, which again gets looked at and approved and maybe tweaked or changed. So it's not just a slapdash method; there are lots of approvals, especially for press releases.

SPACE.com: How long does it usually take to go through all of this?

Cook: It's really nice to have at least a couple of weeks. We have done this in as short as about 48 hours, but if the deadline's short and there are several people who have to weigh in, I tell them, "You'd better be at your computer, checking it every few hours." (Laughs)

SPACE.com: You get in on the ground floor of a lot of exoplanet discoveries. So if an astronomer finds something really exciting — an alien Earth, say — you may know about it before pretty much everyone else in the world.

Cook: If I'm the one who's asked to do the art for it, I will know before everybody else in the world, except for the astronomers and whoever is putting out the press release. That's happened several times, and that's really fun.

I'm given the embargo date, and then I can go to bed one night knowing the embargo lifts at, say, 10 in the morning. Then I can look at my computer, and all of a sudden here's the news all over the world. And I start getting messages — "Oh, Lynette, I saw your work!" It's fun, it really is.

SPACE.com: Do you have any favorites? Do any illustrations stick out in your mind that were particularly fun to do?

Cook: Well, it was really the first few I did that were the most fun. And I think that's because the whole study and discovery of exoplanets was so new, and so amazing.

Probably the first dozen or so really stand out to me over and above more recent ones. And I'll always remember Geoff [Marcy] and Paul's [Butler] first two — those are 47 Ursae Majoris and 70 Virginis. And in terms of my art, HD 222582 — I just love all those twos; it has a really nice sound to it — but I like how my artwork of that came out also. [The Top 5 Potentially Habitable Alien Planets]

SPACE.com: How does your exoplanet art fit in with the rest of your work?

Cook: My space art used to be traditional; that's how work at one time was done when I started out in the field.

The space art ended up going all digital, because that's what clients seemed to require. At one point it was easy to do it traditionally, scan it, get the TIFF file or JPEG and send it off. And that can still be done, but not as easily as it once could, because changes have to be made very quickly. The deadlines and turnaround times are way shorter than they once were.

So that's all gone digital. I miss doing art traditionally, and that's one of the reasons that I am doing fine art at this point. I just don't like being at the computer every day, every hour; it's hard to sit in one place and stare at a monitor, and I don't think it's physically very good for me either, frankly.

SPACE.com: Do you think your illustrations can play a role in this new exoplanet revolution, and how people's perception of their place in the universe is changing?

Cook: Well, they already have. If you look historically at space art, and the role it has played, it is the early space artists who helped get the public excited about going into space, about leaving Earth's orbit. And it seems pretty clear that it is the early artists like [Chesley] Bonestell and others who helped make space travel and space exploration seem possible.

I think today's space artists do the same thing. And with exoplanets, it is one of the areas of astronomy where it's really needed. These planets are so far away that we can't image them directly with any good resolution at all, and the only way for people to really understand what they might be like in a visual way is through the eyes of an artist.

SPACE.com: And a lot of people who are only casually interested in science or space might not actually read the story about a newfound exoplanet. But that picture may stick with them, and that's the whole idea, isn't it?

Cook: It is. And let's face it — there are some people who are very good with words and can really pick up on what text is trying to get across, but large numbers of the population respond visually and will get an idea or a concept visually much more easily than something written.

SPACE.com: Hopefully we'll be able to take pictures of these worlds someday, so we'll know if what you and other artists have envisioned is actually right.

Cook: Yes, won't that be great? Well, I hope it's not too soon. Let's wait a few years for that. Let's wait until I retire, how about that? (Laughs)

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.