Viking 2: Second Landing on Mars

NASA's Viking 2 was a joint orbiter-lander mission that saw the second U.S. landing on Mars on Sept. 3, 1976. Viking 2's lander touched the Red Planet just weeks after its sibling, Viking 1.

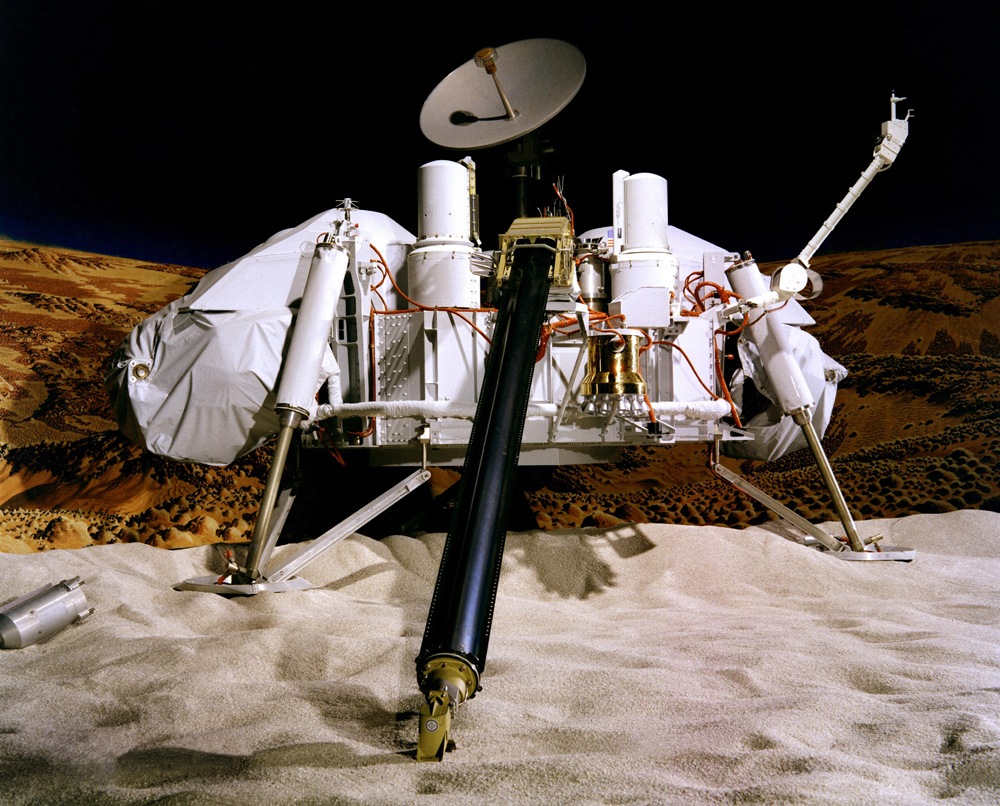

The lander spent more than three Earth years on the surface taking pictures of the surrounding area, analyzing the regolith in front of it, and even conducting life experiments. Meanwhile, the orbiter snapped shots of craters, channels and other Mars features from above.

The Viking program provided the first up-close look at Mars, for several years running. It gave researchers a sense of what it is like to live and work on the Red Planet.

When Vikings 1 and 2 sent back the results of their life experiments, NASA said at the time that there was no definitive evidence of life. That's been called into question in the decades since.

Complexity simplified

The entire Viking program hardware – two orbiters and two landers – cost $1 billion in 1970s dollars, or anywhere from $4 billion to $6 billion today.

While that is a large sum, this is actually half the cost of a proposed NASA Mars landing program called Voyager. (This shouldn't be confused with the solar system probes Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which inherited the name after the Mars program was cancelled.)

Voyager was supposed to fly to Mars using a Saturn V rocket, the same rocket that took astronauts to the moon between 1968 and 1972. The Voyager lander would last two Earth years on the surface.

However, NASA had less money to go around after the Apollo program finished and congressional priorities shifted. The agency was facing a money crunch, and elected to shelve the program in favor of something simpler.

That's not to say that Viking was unambitious. If all went as planned, NASA would do two "soft" landings on Mars – something the agency had never attempted before. The landers would function for at least 90 Earth days or 120 Martian "sols" on the surface. Meanwhile, the orbiters would carry the landers to Mars and send scientific information back to Earth.

If one mission failed, at least there would be a backup, but it would be a high-profile failure: Mars missions usually get the attention of the world.

Viking 2 took its ride into space on a Titan rocket on Sept. 9, 1975, following in the footsteps of its twin, Viking 1. There was a hair-raising few minutes during launch when all data from the spacecraft ceased flowing to Earth, but it picked up again.

Viking 1 famously postponed its landing several weeks to July 20, 1976, because a close-up view of its prime landing site showed it was a perilous spot for a lander. NASA had made the initial decision on a landing site based on Mariner 9's pictures, but Viking 1's superior picture resolution showed a far more perilous terrain than originally thought.

The final selection on Viking 2's landing site also took time; its prime landing site at Cydonia looked treacherous in Viking 1's photographs. Scientists waited until Viking 2 was in orbit before making their final determination on where to go. The resulting location – Utopia Planitia – was selected with both safety and scientific merit in mind.

After a site had been decided, the drama wasn't over as the Viking 2 orbiter lost power to its gyroscope stabilizers shortly after its lander separated. The drifting spacecraft then lost contact with Earth as its antennas pointed in the wrong direction. Fortunately, the computer figured out there was a problem and stabilized the orbiter.

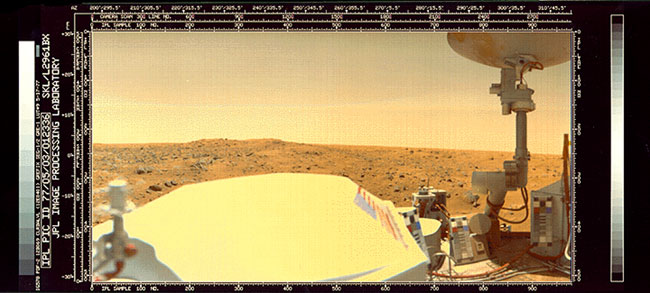

Nevertheless, Viking 2 touched down safely on Sept. 3, 1976. NASA was still fixing the orbiter after touchdown, but the agency was soon able to relay pictures from the surface.

Marsquakes and layered craters

At a glance, Viking 2's landing site appeared much rockier than where Viking 1 was. Scientists observed that the spacecraft appeared to be tilted in the pictures, indicating that it probably touched down on a rock.

Over time, the scientists determined that the rocks scattered nearby Viking 2 probably came from the same origins. NASA suggested the rocks were either broken-up bits from an ancient lava flow, or perhaps a pile of rubble ejected after a nearby crater was formed.

Viking 2's seismometer ended up being one of its most versatile instruments. The spacecraft measured "Marsquakes" on the surface to learn more about the crust on the Red Planet. Scientists estimated the crust underneath Viking 2 was between 8.7 and 11.2 miles (14 and 18 kilometers) thick — about half as thick as continental land on Earth, but much thicker than oceanic crust.

To scientists' surprise, the seismometer was so sensitive that it also could measure wind pressure. "Like the meteorologists, the seismology team detected the cold fronts," NASA wrote in "On Mars: Exploration of the Red Planet 1958-1972." Because Viking 1's seismometer failed, this made Viking 2's findings all the more important.

While Viking 2's lander got the lion's share of media attention, the orbiter was producing science on its own.

The Viking program, for example, revealed that impact craters on Mars show more complex ejecta patterns than on the moon or Mercury. The ejecta appear to be in layers, and include features such as scarps and ridges.

Scientists speculated that the composition of Mars was making the ejecta look different. Perhaps it was groundwater, or melting ice, that caused these patterns when a meteor struck the surface.

Controversial life experiment

Both Viking 2 and its sibling, Viking 1, carried primitive tools to search for Mars life. In the 1970s, NASA and many other researchers interpreted their results to mean that the landers did not find evidence of life. That's been called into question in more recent times.

The Viking experiments had several parts to their life detection experiments, but there is one aspect that has come under more scrutiny. Essentially, what the Vikings did was scoop a bit of the Martian regolith, heat it to 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 Celsius), and then combed for signs of organics.

The landers didn't find any life, but researchers in the years following were curious about whether the experiments were adequately designed to detect lifeforms. Several studies in more recent years have suggested the Vikings perhaps did find life.

In 2006, a team of researchers journeyed to Martian environments on Earth, such as deserts in Peru and Chile, and an Antarctic dry valley. Using different instruments than Viking, they found organic compounds and suggested the Viking landers just weren't sensitive enough.

Four years later, a different group of researchers went a step further and said Viking could have destroyed any organics it found while performing the experiments. Part of their conclusions came from a 2008 discovery by Mars Phoenix of perchlorate (a chlorine-containing chemical) at its landing site.

The researchers assumed the Viking sites also had perchlorate. They then took Mars-like soil that had organics in it and stuck perchlorate inside the soil before heating it up. Scientists detected chloromethane and dichloromethane afterwards – the same results as Viking. Because organics break down into those substances when heated, the scientists argued Viking did heat organics.

Life searches on Mars continue today. Right now, the Mars Curiosity lander is roaming the planet in search for signs of habitability, although NASA says it doesn't have the ability to find life itself.

— Elizabeth Howell, SPACE.com Contributor

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.