Halley's Comet: Facts about history's most famous comet

Halley's Comet is arguably the most famous comet in history.

As a "periodic" comet, it returns to Earth's vicinity about every 75 years, making it possible for a person to see it twice in their lifetime. It was last here in 1986, and it is projected to return in 2061.

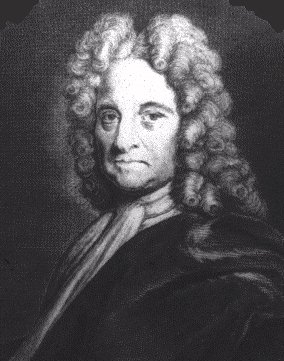

The comet, officially called 1P/Halley, is named after English astronomer Edmond Halley, who examined reports of a comet approaching Earth in 1531, 1607 and 1682. He concluded that these three comets were actually the same comet returning over and over again, and predicted that it would return in 1758. Halley's calculations showed that at least some comets orbit the sun.

Halley didn't live to see the comet's correctly-predicted return, but the comet was given his name. (For those looking for help with pronunciation, the name traditionally rhymes with the word valley.)

Photos: Halley's Comet Through History

Scientists finally got an up-close look at the comet when it last visited in 1986 when several spacecraft were sent to Halley's vicinity to sample its composition. High-powered telescopes also observed the comet as it swung by Earth.

While the comet won't be back for up-close study for decades, scientists continue to investigate comets, looking at other small bodies. A notable example was the Rosetta probe, which looked at Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko between 2014 and 2016 and concluded that the comet has a different kind of water than Earth's water.

The history of Halley's comet

The first known observation of Halley's Comet, or Comet Halley, took place in 239 B.C., according to the European Space Agency. Chinese astronomers recorded its passage in the Shih Chi and Wen Hsien Thung Khao chronicles. Another study (based on models of Halley's orbit) pushes that first observation back to 466 B.C., which would have made it visible by the Ancient Greeks.

When Halley's returned in 164 B.C. and again in 87 B.C., it probably was noted in Babylonian records now housed at the British Museum in London.

"These texts have important bearing on the orbital motion of the comet in the ancient past," a research paper in the journal Nature noted about the tablets.

It's also thought that another appearance of the comet in 1301 could have inspired Italian painter Giotto's rendering of the Star of Bethlehem in "The Adoration of the Magi," according to the Britannica encyclopedia.

Halley's most famous appearance occurred shortly before the 1066 invasion of England by William the Conqueror. It is said that William believed the comet heralded his success. In any case, the comet was put on the Bayeux Tapestry — which chronicles the invasion — in William's honor.

Astronomers in these times, however, saw each appearance of Halley's Comet as an isolated event. Comets were often foreseen as a sign of great disaster or change.

Even when Shakespeare wrote his play "Julius Caesar" around 1600, just 105 years before Edmond Halley calculated that the comet returns over and over again, he included a now-famous phrase sepaking of comets as heralds: "When beggars die there are no comets seen; The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes."

Discovering Halley's comet

Astronomy began changing swiftly around Shakespeare's time, however. Many astronomers of his time believed that Earth was the center of the solar system, but Nicolaus Copernicus — who died about 20 years before Shakespeare's birth — published findings showing that the center was actually the sun.

It took several generations for Copernicus' calculations to take hold in the astronomy community, but when they did, they provided a powerful model for how objects move around the solar system and the universe.

Years passed and the comet appeared in 1531, 1607 and 1682. Halley suggested the same comet could return to Earth in 1758. Halley did not live long enough to see its return (he died in 1742) but his work inspired others to name the comet after him.

On each successive journey to the inner solar system, astronomers on Earth turned their telescopes skyward to watch Halley's approach.

The comet's pass in 1910 was particularly spectacular, as the comet flew by about 13.9 million miles (22.4 million kilometers) from Earth, which is about one-fifteenth the distance between Earth and the sun. On that occasion, Halley's Comet was captured on camera for the first time.

According to biographer Albert Bigelow Paine, the writer Mark Twain said in 1909, "I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it." Twain died on April 21, 1910, one day after perihelion, when the comet emerged from the far side of the sun.

Halley-like comets

There is a group of comets called "Halley family comets" (HFC) because they appear to share the same orbital characteristics of Halley, including being highly inclined to the orbits of Earth and other planets in the solar system. However, this family has a range of inclinations, which prompts other astronomers to suggest they may have a different origin than Halley.

Some suggest these comets could have evolved from members of the Oort Cloud, or from Centaurs (objects that generally have a closest approach between Jupiter and the Kuiper Belt.) Alternatively, HFCs could have come from somewhere just beyond Neptune.

Sending spacecraft to Halley's comet

When Halley's Comet came by Earth in 1986, it was the first time we could send spacecraft to look at it up close.

That was a fortunate occurrence, as the comet ended up being underwhelming in observations from Earth. When the comet made its closest approach to the sun, it was on the opposite side of that star from the Earth — making it a faint and distant object, some 39 million miles (63 million km) away from Earth.

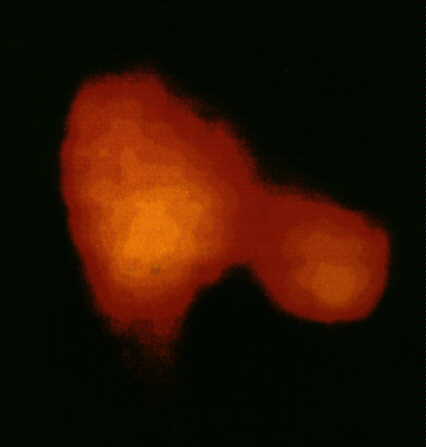

Several spacecraft successfully made the journey to the comet. This fleet of spaceships is sometimes dubbed the "Halley Armada." Two joint Soviet/French probes (Vega 1 and 2) flew nearby, with one of them capturing pictures of the nucleus, or "heart," of the comet for the first time.

The European Space Agency's Giotto craft got even closer to the nucleus, beaming back spectacular images to Earth. Japan sent two probes of its own (Sakigake and Suisei) that also obtained information on Halley.

NASA's International Cometary Explorer (already in orbit since 1978) also captured pictures of Halley, snapping its shots from 17.3 million miles (28 million km) away.

"It was inevitable that this most famous of all comets would receive unprecedented attention, but the actual magnitude of the effort has surprised even most of those involved in it," NASA noted in an account of the event.

The astronauts aboard Challenger's STS-51L mission were also scheduled to look at the comet. But, sadly, they never got the chance. The shuttle exploded about two minutes after launch on Jan. 28, 1986, due to a rocket malfunction, killing all seven astronauts on board.

It will be decades until Halley's gets close to Earth again in 2061, but in the meantime, you can see its remnants every year. The Orionid meteor shower, which is spawned by Halley's fragments, occurs annually in October. Halley's also producedsa shower in May, called the Eta Aquarids.

When Halley's sweeps by Earth in 2061, the comet will be on the same side of the sun as Earth and will be much brighter than in 1986. At least one study has pointed out that it is difficult to predict Halley's orbit on a scale of more than 100 years, and that the comet could collide with another object (or be ejected from the solar system) in as little as 10,000 years, although not all scientists agree with the hypothesis.

When Halley next returns to Earth's vicinity, one astronomer predicted it could be as bright as apparent magnitude -0.3. This is relatively bright, but it won't be the brightest object to skywatchers as it will be well below that of the brightest star in Earth's sky: Sirius, at magnitude -1.4 as seen from Earth.

While it will be decades before we can send another spacecraft to Halley's Comet, there have several other missions that have studied comets from up close. Between 2014 and 2016, for example, the Rosetta probe examined Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko up close and made comparisons to other comets.

One of its key findings was uncovering that Comet 67P had a different kind of water (specifically, a different deuterium-to-hydrogen ratio) than what is seen on Earth. Back in the 1980s, similar examinations of Halley by the Giotto probe also showed that Halley has a different D-to-H ratio in its water than on Earth.

Other notable cometary missions include NASA's Stardust (which captured samples of comet 81P/Wild and returned them to Earth), NASA's Deep Impact (which deliberately sent an impactor into 9P/Tempel on July 4, 2005), and the European Space Agency's Philae (which landed on Comet 67P in 2014.)

This reference page was updated on Jan. 11, 2022 by Space.com senior writer Chelsea Gohd.

Additional resources

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.