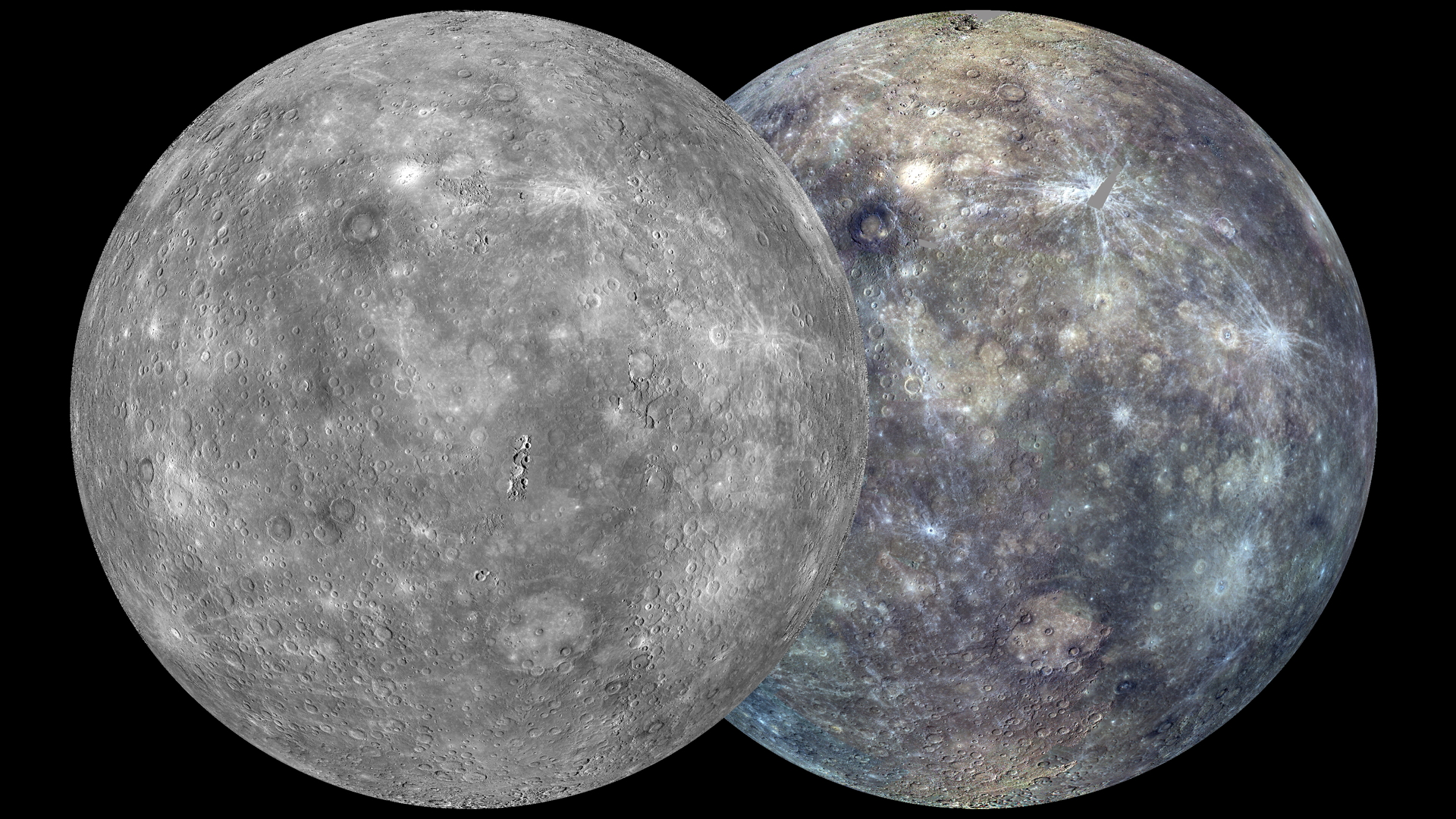

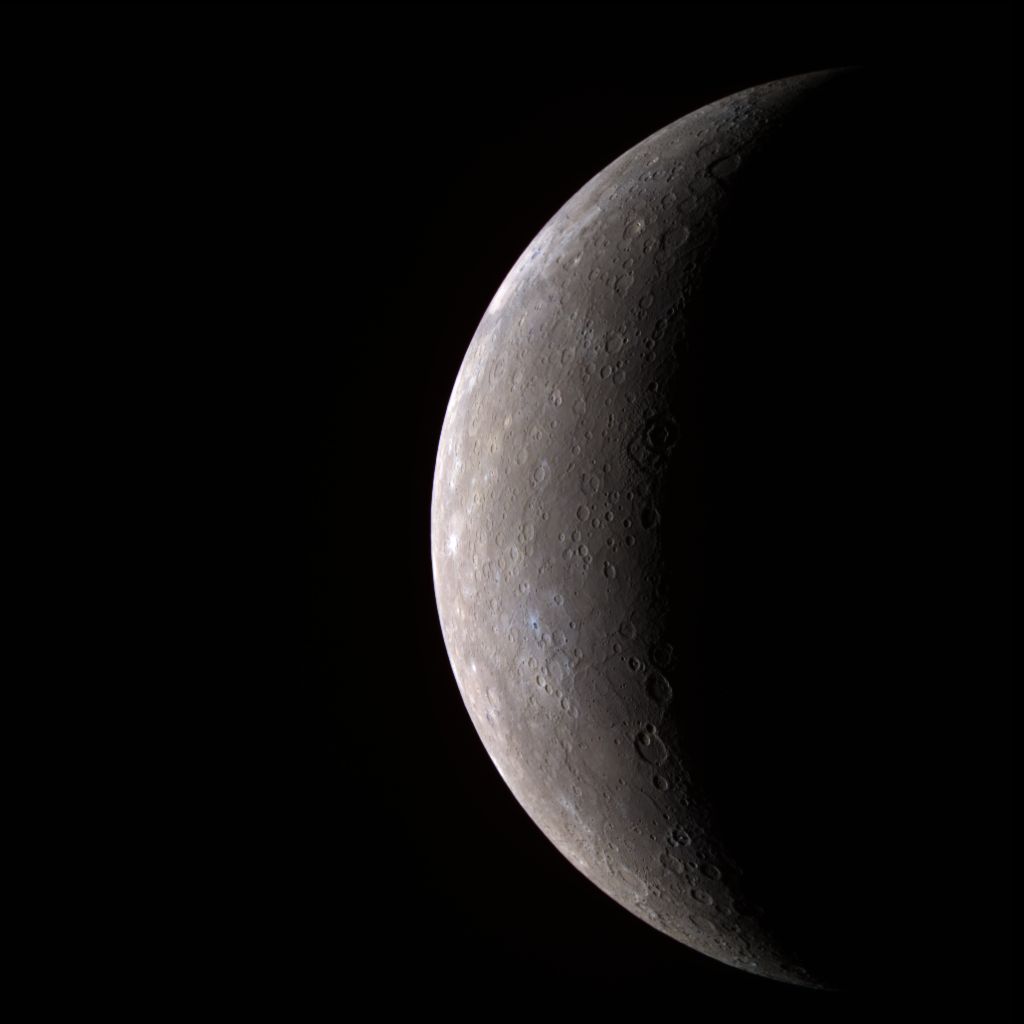

Planet Mercury Once Covered in Magma, Study Suggests

The rocky, mostly dry surface of the planet Mercury may once have been roiling with hot magma, a new study based on observations by NASA's Messenger spacecraft suggests

NASA's Messenger, the first Mercury orbiter, has made its home around the closest planet to the sun since March 2011. From its close-up perch, the probe identified two distinct types of rocks that compose the planet's surface, which scientists were at a loss to explain.

Now, experiments in a lab at MIT suggest Mercury's puzzling surface makeup is most likely explained by a huge ocean of magma that existed shortly after the planet formed about 4.5 billion years ago.

"The thing that's really amazing on Mercury is, this didn't happen yesterday," Timothy Grove, a professor of geology at MIT, said in a statement. "The crust is probably more than 4 billion years old, so this magma ocean is a really ancient feature."

Messenger identified the two rock types using its X-ray spectrometer, which was able to distinguish the chemical composition of materials on the planet's surface. [Latest Photos of Mercury from NASA's Messenger]

Scientists made synthetic rocks in the lab to simulate the two types of material, using finely powdered chemicals to piece together the closest possible matches to what was seen on the planet.

"We just mix these together in the right proportions and we've got a synthetic copy of what's on the surface of Mercury," Grove said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers then subjected these samples to high temperatures and pressures to recreate the conditions they might have experienced throughout Mercury's evolution.

The analysis pointed to only one possible origin for the two rock types, the researchers said. An early ocean of magma created two layers of crystals, which eventually solidified and then re-melted into magma that was spread onto the surface of Mercury through volcanic eruptions.

"We're gradually filling in more blanks, and the story may well change, but this work sets up a framework for thinking about new data," said Larry Nittler, a researcher at the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Nittler led the team that originally identified the two rock types on Mercury, but was not involved in the MIT laboratory study. "It's a very important first step toward going from exciting data to real understanding."

The scientists detailed their findings in the Feb. 1 issue of the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters.

NASA's Messenger spacecraft (the name is short for MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging) launched in 2004 on a $446 million mission to study Mercury like never before. The spacecraft completed its primary mission in 2011 and is nearing the end of its first one-year mission extension.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.