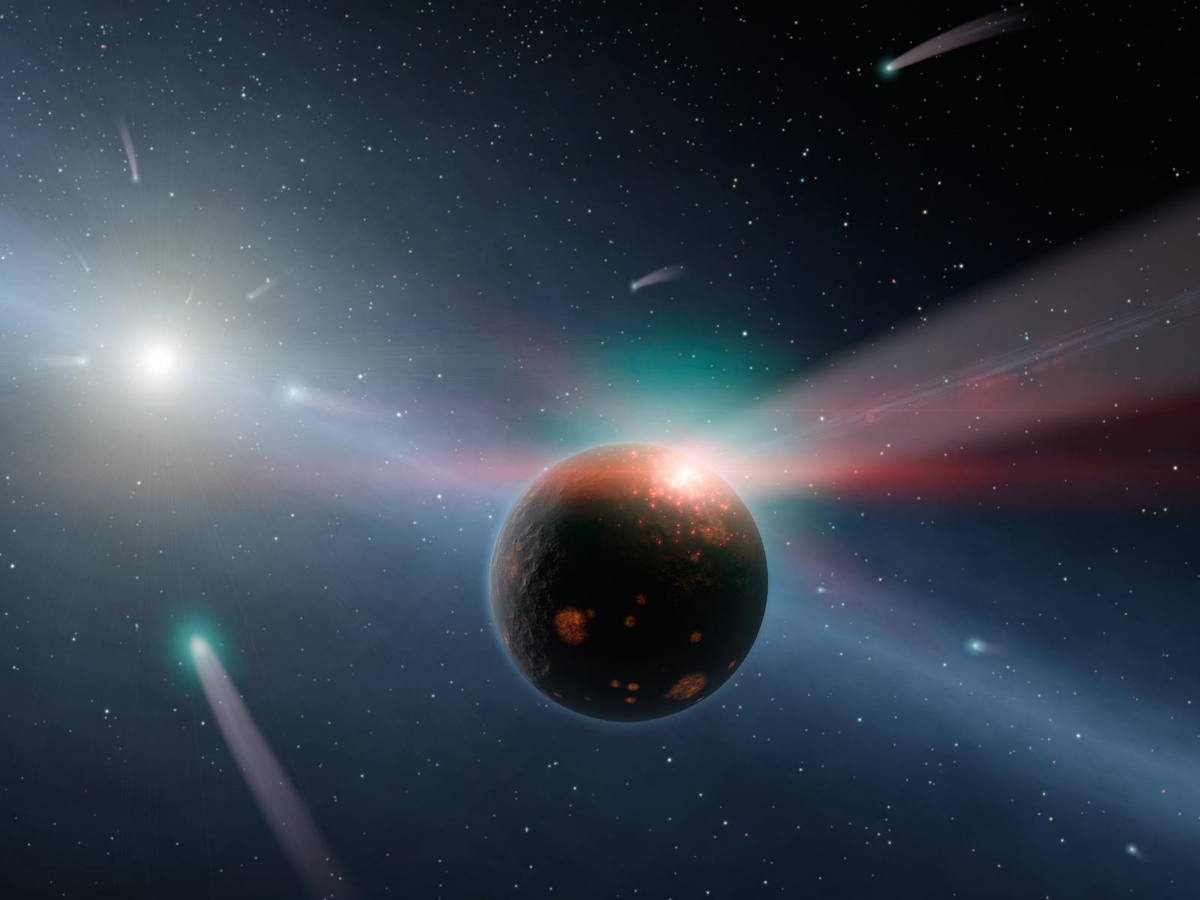

The impact of comets crashing into Earth's surface may have provided the energy to create simple molecules that formed the precursors to life, a new study suggests.

That conclusion, published in the June 20 issue of the Journal of Physical Chemistry A, was based on a computer model of such an impact's effect on a comet crystal initially made up of water, carbon dioxide and other simple molecules.

"Comets carry very simple molecules in them," said study co-author Nir Goldman, a physical chemist at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in California. "When a comet hits a planetary surface, for example, that impact can drive the synthesis of more complicated things that are prebiotic — they're life-building."

Comet collision

The notion that life-building molecules were carried to Earth via comets or asteroids, a hypothesis known as panspermia, has been around for decades. But the idea that the comet impact itself could have created the molecules is newer.

When the Earth was young, comet bombardments may have brought 22 trillion pounds (10 trillion kilograms) of carbon-based material to the planet every year, Goldman said. That would have provided a rich source for the building blocks of life to form. In a separate recent study, scientists zapped a mini-comet in the lab to prove that precursor molecules could form far from Earth. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

To test their hypothesis, Goldman and his colleagues used a computer model to simulate a single comet crystal of hundreds of molecules. Comets are mostly "dirty snowballs," Goldman said, so the simulated crystal started with mostly water molecules, but also included methanol, ammonia, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers then simulated the effects of the crystal hitting the Earth's surface at various angles, from crashing into it directly to making a glancing blow. They followed the chemical changes in the crystal for about 250 picoseconds, about the amount of time the system needed to reach a steady state, where the proportion and type of chemicals in the system is stable. The huge jolt from the impact provided the energy needed to make complicated chemicals.

"Certain conditions were a sweet spot for complexity," Goldman told LiveScience.

For instance, at pressures of about 360,000 times the atmospheric pressure at sea level and temperatures of 4,600 degrees Fahrenheit (2,538 degrees Celsius), the molecules in the crystals formed complex species called aromatic rings. These types of circular, carbon-based molecules could have been precursors to the letters in DNA.

At higher pressures, the molecules produced methane, formaldehyde and some long-chain carbon molecules.

"Every time there was an impact hard enough to get chemical reactivity, it produced interesting stuff," Goldman said.

As a follow-up, Goldman and his colleagues want to test different initial chemical concentrations in the comet to see how that affects the formation process.

No way to prove

The findings are fascinating, said Ralf Kaiser, a physical chemist who studies astrochemistry at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

"It opens another pathway to explain how these biological, or precursor molecules can be formed," Kaiser, who was not involved in the study, told LiveScience.

The team has shown that such precursor molecules "absolutely could be formed this way, no question," Kaiser said.

But it's not all or nothing: Some molecules could have been carried here by comets from outer space, while some formed on impact, and still others formed completely from home-grown materials. The tricky question is to determine what percentage of life's building blocks arose during each process, Kaiser said.

This story was provided by LiveScience.com, a sister site to SPACE.com. Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tia is the assistant managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science, a Space.com sister site. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.