Uranus' moons: A guide to the ice giant's strange tilted moons

Like the ice giant itself, Uranus' moons orbit the sun on their sides and this is just one element that makes them some of the most unusual bodies in the solar system.

The seventh planet from the sun and the coldest planet in the solar system, Uranus has 28 known moons.

These bodies are extraordinary in the solar system because they share the axial tilt of 98 degrees possessed by their parent planet.

Just as Uranus orbits the sun on its side making it the only solar system planet whose equator is nearly at a right angle to its orbit, the moons orbit across the planet's tilted equator perpendicular to the planet's motion around the sun. This indicates that the moons of Uranus formed after a massive collision, possibly with an Earth-sized planet, that knocked the ice giant on its side. In 2017 astronomers suggested that this impact may have actually birthed the moons of Uranus themselves.

Related: The 10 weirdest moons in the solar system

An alternative explanation for the tilt of Uranus, the third largest planet in the solar system after Jupiter and Saturn, published in 2022, suggests it might be the result of a now-lost moon, that has wandered away from the ice giant.

Names and discovery dates

The moons of Uranus also have unique names in the solar system, Whereas the normal naming convention is for celestial objects to share monikers with mythical figures, instead, most of Uranus' moons are named are characters created by William Shakespeare, with only a couple taking their names from the works of Alexander Pope.

The first moons of Uranus to be discovered, Oberon and Titania, were found by German-born astronomer William Herschel in 1787. Herschel had discovered Uranus itself six years earlier in March 1781. The next two moons of Uranus to be discovered, Ariel and Umbriel, were spotted by English astronomer William Lassell in 1851. The next Uranus moon was not discovered until almost a century later when Dutch astronomer Gerard Kuiper found the fifth moon, Miranda, in 1948.

In 1986 the slow period of Uranian moon discoveries would be offset by a burst of discoveries. Making its flyby of the Uranian system Voyager 2 tripled the number of known moons all with diameters of between 16 and 96 miles (26 and 154 kilometers) according to NASA. These moons were Juliet, Puck, Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Desdemona, Portia, Rosalind, Cressida, and Belinda.

Since then the task of discovering Uranus' moons has fallen to the Hubble Space Telescope and improved ground-based telescopes. This is no mean feat as these bodies are extremely dark, "blacker than asphalt" according to NASA, are located 1.8 billion miles (2.9 billion km) away from the sun, and also have diameters as small as 8 to 10 miles (12 to 16 km).

These instruments have spotted moons that were too small and dark even for Voyager 2 to see on its flyby mission and have raised the total of known Uranian moons to 28.

These are with their discoverer and year of discovery according to NASA's official catalog:

- Ariel — William Lassell (1851)

- Belinda — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Bianca — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Caliban — Palomar Observatory (1997)

- Cordelia — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Cressida — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Cupid — Hubble Space Telescope (2003)

- Desdemona — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Ferdinand — Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (2001)

- Francisco — Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (2001)

- Juliet — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Mab — Hubble Space Telescope (2003)

- Margaret — Mauna Kea Observatory (2003)

- Miranda — Gerard P. Kuiper at McDonald Observatory (1948)

- Oberon — William Herschel (1787)

- Ophelia — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Perdita — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Portia — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Prospero — Mauna Kea Observatory (1999)

- Puck — Voyager 2 (Dec. 1985)

- Rosalind — Voyager 2 (1986)

- Setebos — Mauna Kea Observatory (1999)

- Stephano — Mauna Kea Observatory (1999)

- Sycorax — Palomar Observatory (1997)

- Titania — William Herschel (1787)

- Trinculo — Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (2001)

- Umbriel — William Lassell (1851)

Uranus' moons FAQs answered by an expert

We asked Ravit Helled, a planetary scientist specializing in planet formation, planet interiors, planetary evolution, and solar system physics a few commonly asked questions about the moons of Uranus.

Ravit Helled is a Professor at the Institute for Computational Science, Center for Theoretical Astrophysics and Cosmology, University of Zurich, who specializes in planet formation, planet interiors, planetary evolution, and solar system physics.

Could Uranus have any undiscovered moons?

Certainly. The irregular moons are on more elliptical, inclined, or retrograde orbits and are probably captured small objects that were captured by Uranus' gravity field. They are small and hard to detect, so in principle, there is no reason to believe that we discovered all of them.

What is Uranus' most interesting moon?

To me, all the regular moons are extremely interesting since they can reveal information on Uranus' origin and early evolution. The surfaces of Uranus's five mid-sized moons exhibit extreme geologic diversity, demonstrating a complex and varied history.

Most of the major Uranian moons could host a residual ocean a few tens of kilometers thick at present, except for Miranda - so we really need to explore them. The heat source for the planets comes from tidal interactions with the planet (like with the regular moons of Jupiter and Saturn) which probably played a key role in the evolution of the Uranian satellite system. Intense tidal heating during sporadic passages through resonances could have induced internal melting in some of the icy moons.

What are Uranus' moons made of?

We don't really know. This is where having a dedicated mission to investigate Uranus and its moons would be a game changer. We think that the regular moons consist of mostly rock and ices, about 50%-50%, with the innermost satellite Miranda being the most icy one. But the data are not that great, so there is a large uncertainty in this estimate.

The inner moons are expected to have a similar composition to the ring particles, so probably mostly dust. The composition of the moons beyond Oberon's orbit is unknown, but they are likely captured asteroids, so probably rocky in composition, but possibly also ice and other elements.

Is there anything unique about the moons of Uranus?

The most unique feature is that the regular moons are tilted together with Uranus. The tilt of Uranus is peculiar in the solar system, and the fact that the moons are also tilted imply that they formed after Uranus got tilted. Also, the regular Uranian satellite system has a positive trend in the mass-distance distribution and possibly also in the bulk density — this also hints that they formed from a disk. Exploring Uranus' moons can reveal how ocean worlds may form and remain active, defining the extent of the habitable zone in the solar system. As a result, a future mission to explore Uranus and its moons is highly desirable (and a Uranus Flagship mission is indeed recommended by the U.S. planetary decadal survey).

Uranus' largest moons and its "Frankenstein's Monster"

Titania is the largest moon of Uranus, with a diameter of around 1,000 miles (1,609 km), which still makes it under half as wide as Earth's moon which has a diameter of around 2,200 miles (3,500 km). It is also the eighth most massive moon in the solar system.

Taking its name from the queen of the fairies in A Midsummer Night's Dream, Titania is gray in color and features highly reflective patches that astronomers believe are frost. Titania is considered to be composed of a slushy ice mantle over a solid rocky core, with its mass equally divided between ice and rock. This is something it has in common with all of the inner Uranian moons.

The next largest moon of Uranus is Oberon, which takes its name from the king of the fairies in Shakespeare's "A Midsummer Night's Dream." This moon has a diameter of around 946 miles (1,500 km). As well as being a similar size to its celestial "wife" Titania, Oberon has a similar half-ice/half-rock composition. Oberon is distinct from Titania and the other large moons of Uranus because its surface is much more heavily cratered than the surfaces of the other Uranian moons.

Umbriel and Ariel are the third and fourth largest moons of the Uranian system with diameters of 726 miles (1,168 km) and 718 miles (1,156 km) respectively.

Umbriel, named for a malevolent spirit in Alexander Pope's 18th-century poem "Rape of the Lock," is the darkest of Uranus' largest moons. According to NASA, it reflects only 16% of the light that falls on its surface. Quite how the surface of Umbriel became so dark is a mystery.

Another mystery surrounding this dark moon takes the form of a bright ring about 90 miles (140 km) in diameter on its surface. Scientists believe that this could be the result of frost deposits gathering around an impact crater.

Ariel is a stark contrast to Umbriel, as the brightest of Uranus' large moons, reflecting over a third of the light that strikes its surface. It takes its name from Pope's poem and also from a character in Shakespeare's "The Tempest." Ariel appears to have a surface that is the youngest of the moons of Uranus. This is because, according to NASA, it has just a few small craters indicating recent low-impact collisions that have "wiped out" the large craters left by much earlier and larger impacts.

The innermost of the large Uranian moons is Miranda with a diameter of around 292 miles (470 km) which NASA describes as appearing as if it is composed of parts from different bodies, almost like a celestial Frankenstein's monster.

This strange landscape is punctuated by three large features known as "coronae" not seen on any other known solar system objects. These coronae are lightly cratered collections of ridges and valleys that are walled off from older and more heavily crated regions of Miranda, for the daughter of Prospero in the Shakespeare play, "The Tempest," by sharp boundaries.

Miranda also possesses giant canyons that NASA says are up to 12 times as deep as the Grand Canyon. Quite what has caused the disparity in features across Miranda is hotly debated, with one suggestion being Miranda was once smashed apart by a massive collision and then haphazardly reassembled.

All these large Uranian moons are tidally locked to their parent ice giant meaning, as is the case with Earth's moon, one face of these moons constantly points at the planet.

Shepherd moons

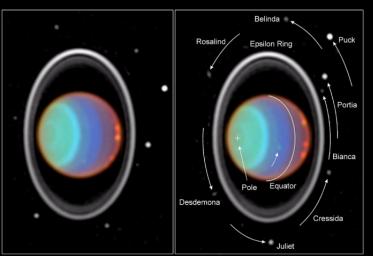

One of Uranus' most interesting features is its ring system and the ice giant's moons play an important role in shaping these rings. Uranus has 13 inner moons and also 13 faint rings and the two are intimately connected.

In particular, Cordelia, which is the closest moon to the ice giant's surface, and Ophelia are known as "shepherd moons." As such Cordelia, with a diameter of 9 miles (15 km), and the 13-mile (21-km) wide Ophelia act to keep the particles that form the thin blue-colored outer ring, epsilon, together.

Between Cordelia and Ophelia and Miranda are at least eight small satellites which make this region extremely crowded. Not only is this band around Uranus like nothing else seen in the solar system, but NASA says scientists haven't yet discovered how these tiny moons avoid crashing into each other.

Just as Cordelia and Ophelia act as shepherds for the outermost ring, these small Uranian moons may hold the particles that comprise the ten innermost red-hued rings of the ice giant, Zeta, 6, 5, 4, Alpha, Beta, Eta, Gamma, Delta, Lambda, together.

While the composition of the inner Uranian moons is roughly half ice, and half rock, the composition of the smaller outer moons is mostly unknown. NASA suggests they are probably asteroids captured by the massive gravitational influence of the solar system's third-largest planet.

Can we see Uranus' moons?

While the planet Uranus is fairly easy to spot from Earth, even its largest moons are tough to observe according to the British Astronomical Association. Four of the Uranian moons, Titania, Oberon, Umbriel, and Ariel, can be seen with medium to large telescopes and some care. The latter two moons are a more challenging observational target due to their proximity to the bright glow of Uranus.

In good viewing conditions and with larger telescopes it is also possible to see some of the fainter and smaller Uranian moons from Earth. For instance, in Sept. 2020, British astronomer Paul Leyland was able to catch an image of the small moon Sycorax, which has a diameter of about 93 miles (150 km).

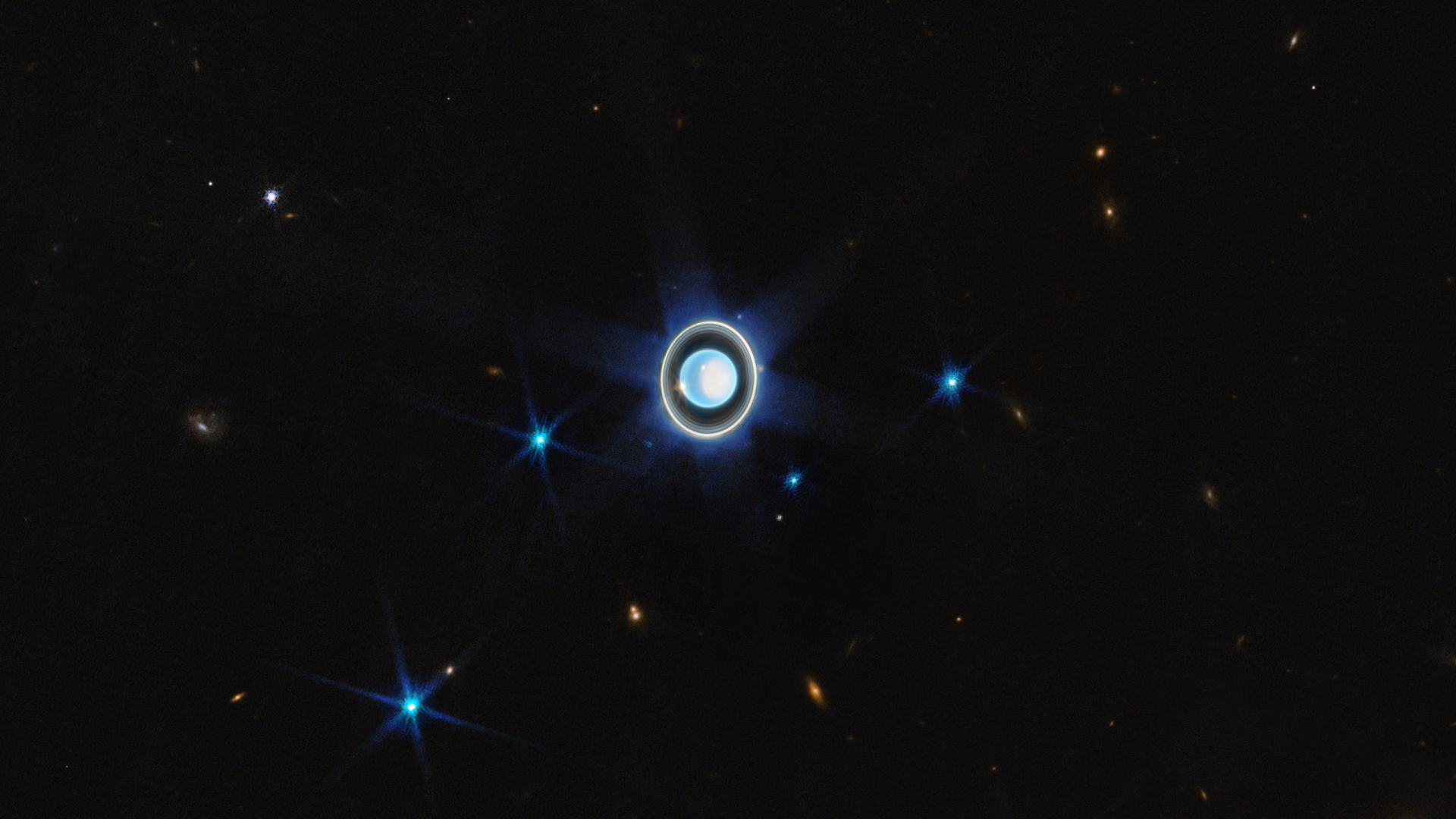

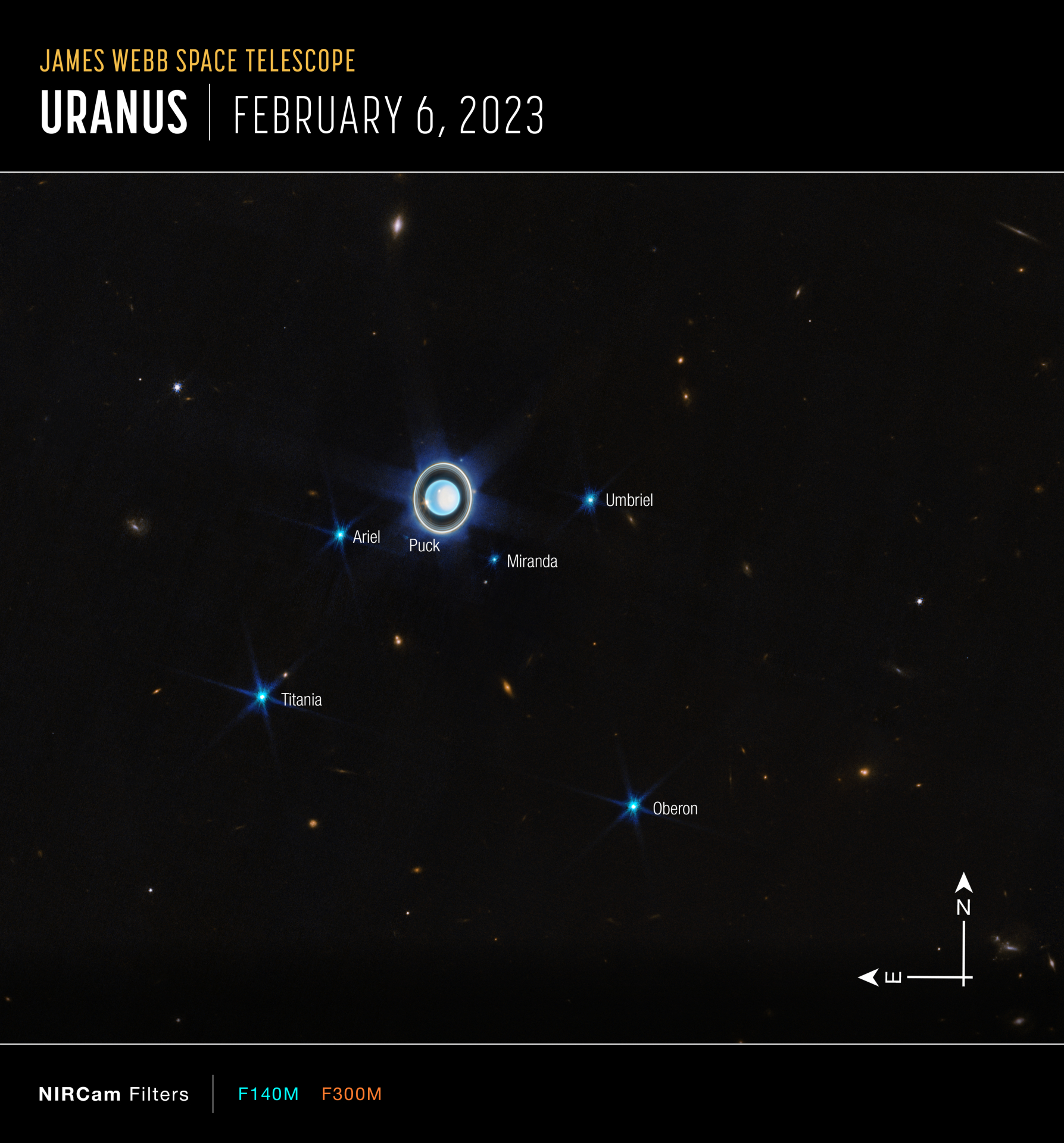

In April 2023, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) captured a stunning image of Uranus showing the ice giant in incredible detail. In addition to featuring the planet's ring system, some including the faintest rings Nu, and Mu which haven't been seen since Voyager 2 visited the Uranian system in 1986, the image featured the largest five moons of Uranus and also Puck, which has a diameter of around 90 miles (150 km).

Additional resources

Only one spacecraft has ever visited Uranus and its moons, NASA's Voyager 2 mission which eventually became the second spacecraft to leave the solar system and reach interstellar space. Read about it here in these resources from NASA. The outer solar system is ruled by the ice giants Uranus and its twin planet Neptune. Amy Simon explains the realm of the ice giants on the Planetary Society website

Bibliography

Uranus moons, NASA, accessed 04/18/23, solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/uranus-moons/overview/

Moons of Uranus, Exploring the Planets, National Air and Space Museum, accessed 04/18/23, https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/exploring-the-planets/online/solar-system/uranus/moons.cfm

Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters, NASA JPL, accessed 04/18/23, https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sats/phys_par/

Uranus (NIRCam Compass Image), Webb Space Telescope, [2023], https://webbtelescope.org/contents/media/images/2023/117/01GWQDSFM5JFT8D8D2GHCBEY23

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.