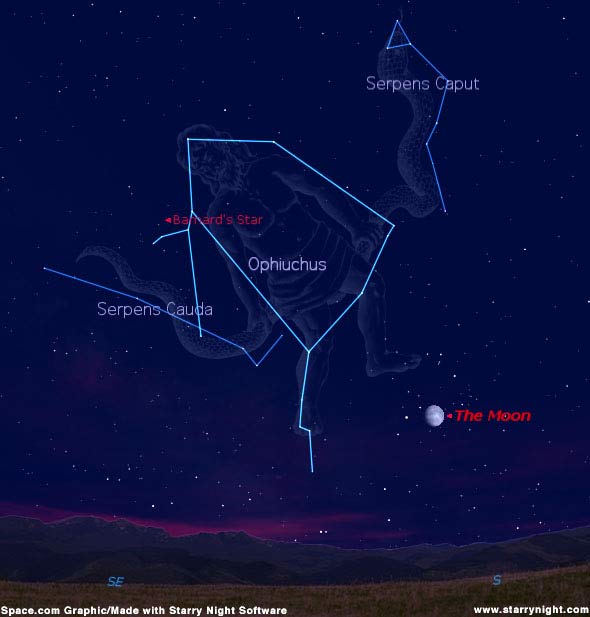

During the evening hours during this week, as the bright Moon moves away to the east, we can look high toward the southern part of the sky and trace out the "celestial medicine man" Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer, a star pattern that is teamed with the constellation Serpens.

King James I of England, who reigned in the 1600s, once referred to Ophiuchus as "a mediciner after made a god," because the Serpent Bearer was often identified with Aesculapius, who in Greek Mythology, was originally a mortal physician who never lost a patient by death. This alarmed Hades, god of the dead, who prevailed on his brother, Zeus, to liquidate Aesculapius.

In recognition of his merits, however, Aesculapius was put up into the sky as a constellation.

In the sky he appears not so much like a man but more like a large upended oblong structure with a peaked roof where a star as bright as the North Star appears to shine. That star is the brightest of Ophiuchus and is known as Ras Alhague, the "head of the Serpent Holder." [Map]

An oddity about Ophiuchus is that the ecliptic-the apparent path of the Sun, Moon and planets-actually cuts through this constellation. In fact, the Sun spends more time traversing through Ophiuchus than Scorpius! It officially resides in Scorpius for less than a week: from November 23 through 29. It then moves into Ophiuchus on November 30 and remains within its boundaries for more than two weeks-until Dec. 17. Yet the Serpent Holder is not considered a member of the Zodiac and so must defer to Scorpius! Perhaps the reason was that in order to include Ophiuchus, there would have been an unlucky thirteen "Houses of the Sun" instead of the currently accepted twelve.

Serpens the Snake is the only constellation cut in two. The Serpent's head lies west of Ophiuchus and is known as Serpens Caput; while to the east of Ophiuchus lies smaller Serpens Cauda, the tail. Four stars mark the head of Serpens. The three brightest-Beta, Gamma and Kappa Serpentis-are set in a nearly equilateral triangle.

Off to the south of the Serpent's head is Messier 5, one of the finest globular clusters. Believed to contain over a half million stars, M5 can just be seen without optical aid as a fuzzy "star" on a dark, clear night.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Small binoculars show a tiny fuzz ball, while giant binoculars show the cluster rapidly brightening toward the center with a slight hint of a mottled texture. The late Walter Scott Houston, who for many years edited the Deep Sky Wonders column for Sky & Telescope magazine once wrote of M5: "It is one of the better globular star clusters for small telescopes, because it actually gives the impression of being a cluster rather than an amorphous glow."

In 1916, Edward Emerson Barnard (1857-1923) discovered a star in Ophiuchus that appeared to move against the general star background at a far more rapid pace across our line of sight than most of the other stars.

Now called Barnard's "Runaway Star," a 9.5 magnitude (binoculars are necessary) red dwarf star. It is traveling toward the north at 10.3 arc seconds per year, the record for proper motion, which is the apparent motion of a star against the background of fixed stars. It's only six light years from Earth, and ranks as the second-nearest star to the solar system. Its actual velocity through space is about 103 miles per second.

The association with a serpent may have come from the belief that, by shedding its own skin, it is rejuvenated. And to this day, the symbol of the medical profession is the caduceus, which is a winged staff with serpents twined around it.

Basic Sky Guides

- Full Moon Fever

- Astrophotography 101

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- 10 Steps to Rewarding Stargazing

- Understanding the Ecliptic and the Zodiac

- False Dawn: All about the Zodiacal Light

- Reading Weather in the Sun, Moon and Stars

- How and Why the Night Sky Changes with the Seasons

- Night Sky Main Page: More Skywatching News & Features

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

| DEFINITIONS |

1 AU, or astronomical unit, is the distance from the Sun to Earth, or about 93 million miles. Magnitude is the standard by which astronomers measure the apparent brightness of objects that appear in the sky. The lower the number, the brighter the object. The brightest stars in the sky are categorized as zero or first magnitude. Negative magnitudes are reserved for the most brilliant objects: the brightest star is Sirius (-1.4); the full Moon is -12.7; the Sun is -26.7. The faintest stars visible under dark skies are around +6. Degrees measure apparent sizes of objects or distances in the sky, as seen from our vantage point. The Moon is one-half degree in width. The width of your fist held at arm's length is about 10 degrees. The distance from the horizon to the overhead point (called the zenith) is equal to 90 degrees. Declination is the angular distance measured in degrees, of a celestial body north or south of the celestial equator. If, for an example, a certain star is said to have a declination of +20 degrees, it is located 20 degrees north of the celestial equator. Declination is to a celestial globe as latitude is to a terrestrial globe. Arc seconds are sometimes used to define the measurement of a sky object's angular diameter. One degree is equal to 60 arc minutes. One arc minute is equal to 60 arc seconds. The Moon appears (on average), one half-degree across, or 30 arc minutes, or 1800 arc seconds. If the disk of Mars is 20 arc seconds across, we can also say that it is 1/90 the apparent width of the Moon (since 1800 divided by 20 equals 90). |

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.