'Sparky' Discovery Reveals How Early Universe Built Galaxies

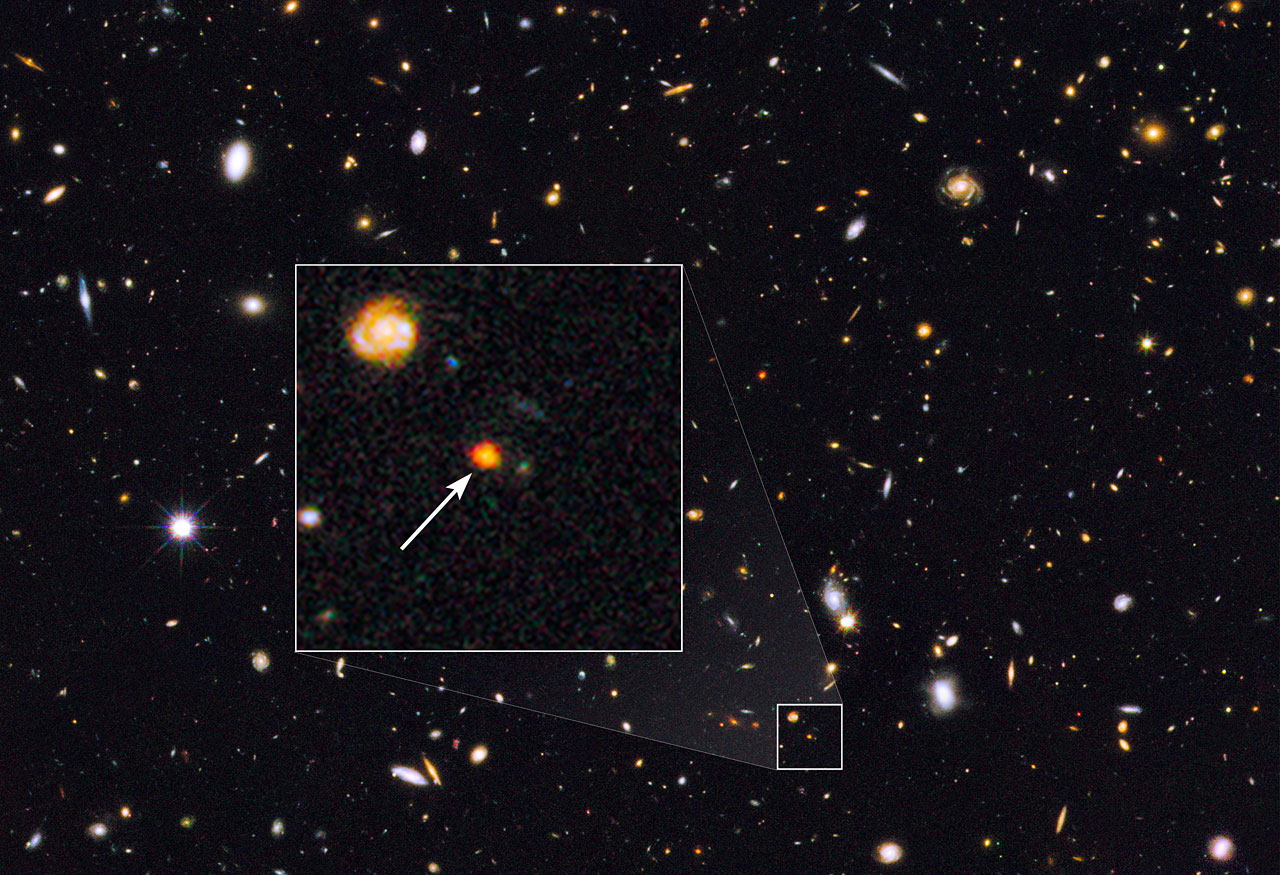

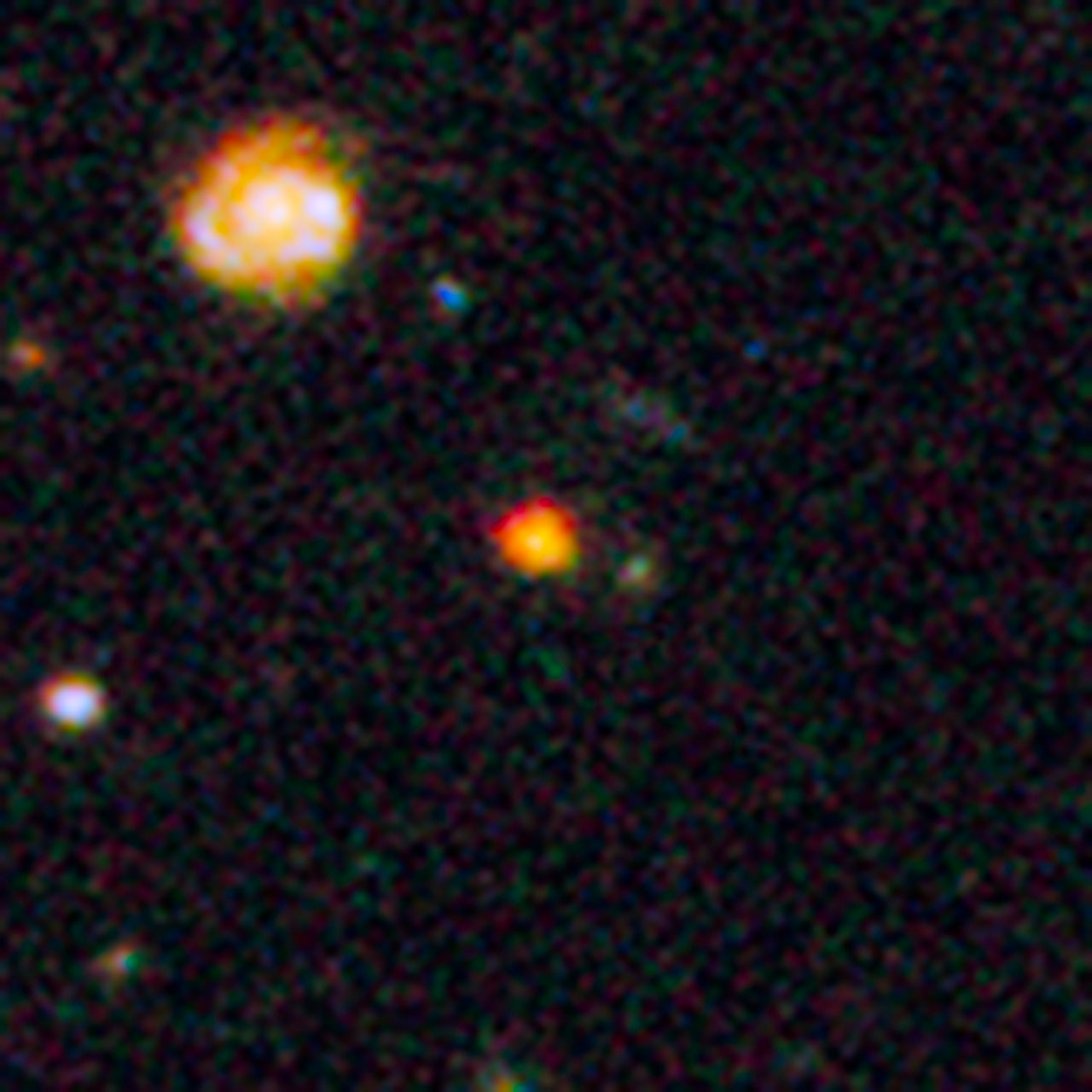

A burgeoning galactic core nicknamed "Sparky" is showing scientists how galaxies grew and evolved early in the universe's history.

Multiple telescopes on the ground and in space gathered information on Sparky, which is more formally known as GOODS-N-774. The half-built galaxy lies 11 billion light-years from Earth, so viewing it gives astronomers a glimpse into processes that occurred less than 3 billion years after the Big Bang that created the universe.

"It's a formation process that can't happen anymore," study lead author Erica Nelson, a graduate student at Yale University in Connecticut, said in a statement. "The early universe could make these galaxies, but the modern universe can't. It was this hotter, more turbulent place." [Galactic Core 'Sparky' Churning Out Stars (Video)]

The dramatic starscape confirms a longstanding theory that huge elliptical galaxies form core-first, researchers said. Elliptical galaxies — the most numerous type in the universe — are primarily composed of older stars and generally have little gas left in them.

Astronomers first looked at Sparky with an infrared camera on NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, then examined the galaxy by looking at archival images from the agency's Spitzer Space Telescope and Europe's Herschel Space Observatory, which ceased operations in 2013.

The various observations revealed that Sparky is creating about 300 stars per year, more than 30 times the rate in Earth's own Milky Way galaxy. Sparky's prolific nature is even more impressive considering its diminutive size; the galaxy is only about 6,000 light-years across, compared to the Milky Way's 100,000 light-years.

Astronomers got more details about Sparky's formation using a near-infrared spectrograph on the Keck Observatory in Hawaii. Keck revealed gas clouds quickly orbiting around the galaxy's center, providing the material needed to create young stars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Further, a thick layer of dust covers the galaxy, so even more stars could be forming while remaining unseen, researchers said.

"It's like a medieval cauldron forging stars. There's a lot of turbulence, and it's bubbling," Nelson said. "If you were in there, the night sky would be bright with young stars, and there would be a lot of dust, gas and remnants of exploding stars. To actually see this happening is fascinating."

The stellar baby boom was likely fueled by a huge stream of gas flowing into the galactic core, which houses a substantial amount of dark matter, a mysterious substance believed to form the backbone of galaxies.

The next goal is to find out how often this sort of situation occurred in the early universe. Astronomers said learning such details will likely require more-sensitive infrared telescopes, such as NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope, which is scheduled to launch in 2018.

A paper on the research was published in the Aug. 27 edition of the journal Nature.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or Space.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.