Is This the Loneliest Galaxy In the Universe?

The universe has structure: long filaments of dark matter threaded with galaxies and clusters of galaxies punctuated by vast voids. These voids are just that; devoid of the rich concoction of stars that are beaded along the universal 3-dimensional web of matter. But, as this Hubble Space Telescope observation shows, not all voids are completely empty.

ANALYSIS: Mysterious 'Cold Spot': Fingerprint of Largest Structure in the Universe?

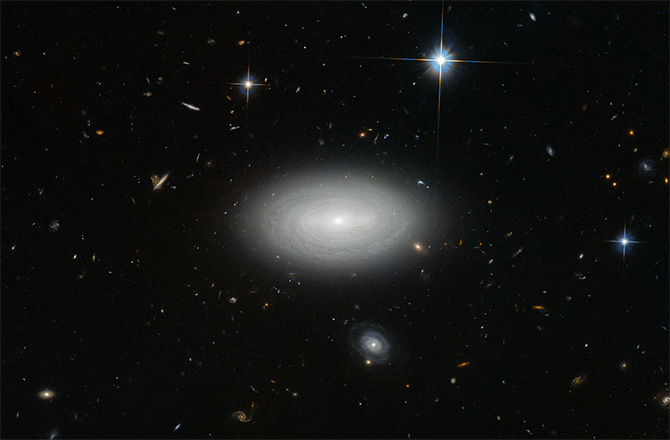

This spiral beauty, as seen by Hubble's Advanced Camera for Surveys, has the unromantic designation of "MCG+01-02-015," but it's situation inspired the European Space Agency to describe it as "the loneliest of galaxies" — a galaxy that is stuck inside the famous Boötes void.

How the galaxy got there, it is not known. Perhaps it was it born there? Did an island of gas find itself in the middle of a sparsely populated volume of the cosmos, only to spark its galactic evolution in solitary confinement? Or did some gravitational turmoil, billions of years in the galaxy's past, hurl MCG+01-02-015 into the void?

PHOTOS: Hubble's Sexiest Spiral Galaxies

As lonely as it is, MCG+01-02-015 isn't alone inside the 250 million light-year-wide Boötes void, a small handful of other isolated galaxies live there too. Some theories suggest these "void galaxies" may be some of the most pristine examples of galactic evolution, having been formed in near-isolation away from the turmoil of other galactic encounters, forming from the soup of primordial intergalactic gases. And looking at MCG+01-02-015, it does look like a picture-perfect spiral galaxy.

Included in this observation are 3 foreground stars, all from our own galaxy — those 3 points of bright light with obvious diffraction spikes. But these are the only individual stars in Hubble's field of view, all other points of light are background galaxies, each containing billions of stars, some also with elegant spiral structures. Even that spiral galaxy just below of MCG+01-02-015 is far behind and likely out of the void.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

ANALYSIS: Giant Mystery Ring of Galaxies Should Not Exist

Interestingly, according to ESA, "the galaxy is so isolated that if our galaxy, the Milky Way, were to be situated in the same way, we would not have known of the existence of other galaxies until the 1960s." It's hard to imagine how isolated MCG+01-02-015 is, our Milky Way galaxy is living in a thriving galactic metropolis in comparison! For any hypothetical aliens living in the void, lacking advanced telescopes and astronomical imaging techniques, the universe would look like a far different place than what we are accustomed to. They would have very dark skies, save for the stars in their own galaxy.

With the help of powerful space telescopes like Hubble, humankind hasn't only become accustomed to the countless billions of galaxies, we've built a 3-D picture of the "cosmic web" of galaxies, all held together by a gravitational force that can only be there if the majority of the cosmos is composed of an invisible mass called dark matter. But where there are giant filaments of matter, there's monstrous voids separating them and, occasionally, we find inextricable galaxies that have somehow become trapped inside, the undisputed galactic loners of the universe.

This article was provided by Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.