Flyby Comet Was WAY Bigger Than Thought

Comets can be tricky. These interplanetary vagabonds often appear from the furthest-most reaches of the solar system, popping-up unexpectedly in surveys for near-Earth objects (NEOs). Also, they may not even resemble a comet as they're still in deep freeze, not producing their trademark fuzzy coma and tail produced by sublimating ices.

Oh, and often it can be hard to measure their size until they make a close pass of our planet. And sometimes they can give us a fright.

ANALYSIS: Discovery Channel Telescope Helps Identify Incoming Comet

Enter P/2016 BA14, a comet that was first detected as an asteroid by the University of Hawaii's PanSTARRS telescope in January and then re-identified as a comet by the Discovery Channel Telescope at Lowell Observatory in Arizona.

BA14 is notable for a few reasons, but it is now most famous for being the third closest comet flyby in recorded history. On March 22, BA14 came within 2.2 million miles of Earth, that's only 9 times the Earth-moon distance. Interestingly, it flew past Earth only a day later than another comet, 252P/LINEAR, which is a well-known comet having been discovered way back in 2000. Estimates of 252P's nucleus size put it at around 250 meters (820 feet) wide and BA14 was presumed to be around half that size. Due to their similar orbits, astronomers believe both objects were once likely part of the same object that broke up some time in the past.

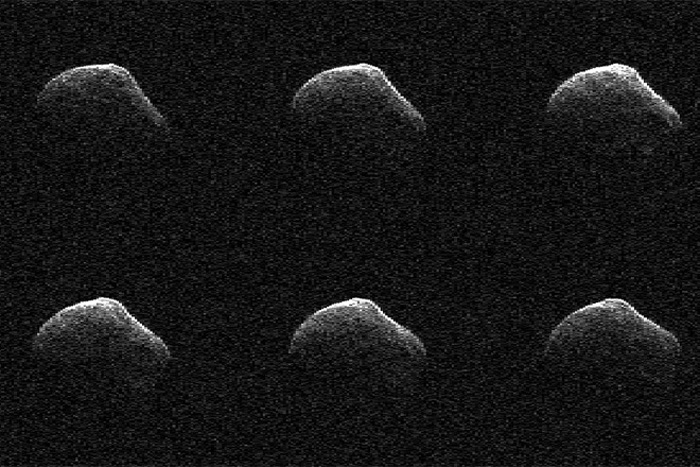

However, as BA14 made its Earthly close encounter last week, NASA's Goldstone Solar System Radar in California's Mojave Desert was able to spend 3 nights observing the object, revealing its spin and true size. This hunk of ancient icy space rock spins once on its axis every 35 to 40 hours is 1 kilometer (3,000 feet) wide! This is a lot bigger than previously estimated, but why the huge discrepancy?

PHOTOS: Discovery Channel Telescope's Epic Cosmic View

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The radar imagery was able to observe important features on the comet's surface that may help scientists better understand the come's origins.

"The radar images show that the comet has an irregular shape: looks like a brick on one side and a pear on the other," said Shantanu Naidu, postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., who led the radar observations. "We can see quite a few signatures related to topographic features such as large flat regions, small concavities and ridges on the surface of the nucleus."

Despite how bright the vapor tails become when lit by sunlight, comet nuclei themselves are often very dark — a contributing factor to the huge uncertainties when estimating cometary dimensions. With the help of NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, astronomers realized that BA14 is only reflecting 3 percent of the sunlight that falls on it, making its comet nucleus "as dark as fresh asphalt," according to a NASA news release.

Its extremely low albedo (reflectivity) is the most likely reason its dimensions were significantly underestimated when the object was first discovered. Astronomical detection of comets and asteroids rely on how much light is reflected off their surface. If they are darker than thought, less light is reflected and size estimates will be underestimated.

ANALYSIS: Comet Double-Whammy: A Lesson in Planetary Defense?

And it seems that's exactly what happened with BA14 — its extremely dark surface hid its true size and only when it got come enough (i.e. flyby) were we able to bounce radar off its surface to see its real bulk.

Now astronomers will be hard at work trying to better understand where this comet came from and how it formed. Scientifically, in-depth studies of comets are important as these objects were formed direct from the protoplanetary disk that condensed around our sun before our Earth formed over 4 billion years ago. Comets are the pristine "time capsules" of our solar system that hide their ice under a dark sooty layer of dust.

But in regards to planetary defense, the discovery of such a significant comet only months before such a close approach with Earth is a troubling reminder of the large NEOs that have still to be discovered. We were never in any danger from this object — its orbit was always giving Earth a wide enough berth — but still, I'm thankful BA14 didn't come any closer.

Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Originally published on Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.