Meet the First Man Who Imaged the Moon

Five decades after helping to land America's first probes on the moon, Justin Rennilson still keeps up with the latest space news. Rennilson, now 89, eagerly watched the Chinese rover Yutu toddling around the moon after it landed in 2013. And he's especially eager to see Americans go back, perhaps through the private company Moon Express.

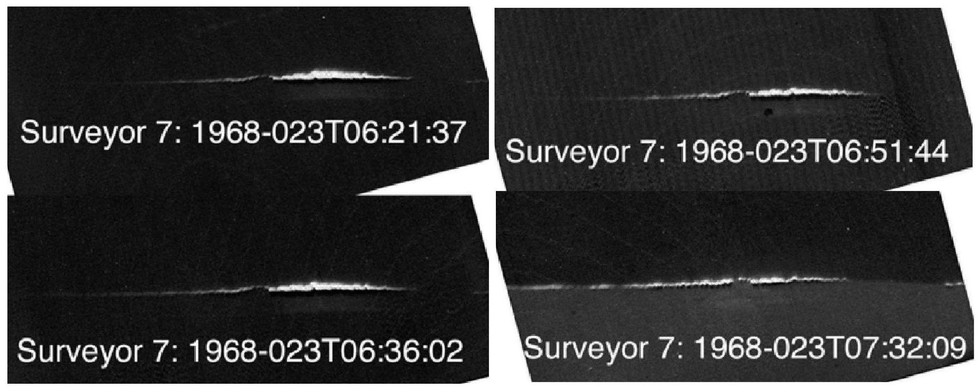

Rennilson assisted with the first camera to take pictures of the moon — Ranger 7 — as well as the camera that flew on Surveyor 1 (which landed 50 years ago last week). There's still science to follow up on from those missions, he says. Among them is a yet-to-be substantianted claim that there could be lunar dust blowing around on the surface every sunrise and sunset. His team spotted a bright line on the horizon on several occasions during Surveyor's program; they suspect the line is showing levitating dust.

RELATED: NASA's First Lunar Landing Happened 50 Years Ago

"If particles go up with (the moon's) electrostatic field, they may not go down at the same place they started from," Rennilson told Discovery News. He is currently helping the University of Arizona digitize 93,000 images from the program -- a project that should be ready for public viewing around late 2016 or early 2017.

Rennilson's journey to the moon began 55 years ago in 1961, when he had a fresh degree focusing on optical physics, and was working at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. A friend told him NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. needed people who knew optics. While Rennilson's wife was reluctant to leave San Diego, the couple moved and Rennilson found himself at the front line of the space race.

RELATED: Moon's Amino Acids Likely Earth Contamination

That year was important in human spaceflight; Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first human in space on April 12, with the United States' Al Shepard following just weeks later, on May 5. Then NASA's mandate got a push from President John F. Kennedy on May 25. He addressed Congress with a speech on "urgent national needs" that in part, ordered his country to "commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It was a tall order for the United States, which had 15 minutes of human spaceflight experience. This is where the Surveyor program and its predecessor, Ranger, became supremely important; they took pictures of the moon and also taught scientists what the surface was like, ahead of the Apollo program that did land humans on the moon on time, in 1969.

RELATED: Moon Landing: Rarely Seen Photos Inside Apollo 11

Rennilson joined JPL's photoscience group that was responsible for all of the imaging characteristics of missions with cameras. Ranger carried "slow-scan" television cameras (meaning the images were read out at a slower rate than standard television at the time). The program endured six failures before successfully impacting Rangers 7, 8 and 9 on the moon as planned between 1964 and 1965. Those missions showed the first American close-up images of the moon.

By this time, Rennilson was working closely with Eugene Shoemaker, one of the founders of planetary science at NASA, and Gerard Kuiper, one of the principal investigators on Ranger and the person who first proposed the existence of the Kuiper Belt at the edge of the solar system. Of the entire Ranger team, only three people are still alive today including Rennilson, he added.

RELATED: Carbon Monoxide 'Fire Fountains' Erupted on the Moon

For Surveyor -- whose goal was to soft-land a probe on the moon -- Rennilson worked on a Bell and Howell camera (Howell is unrelated to the author of this piece) with a zoom system. The team decided, based on the camera's design, to take pictures at the end position for narrow angle shots, and at the opposite position for wide angle shots.

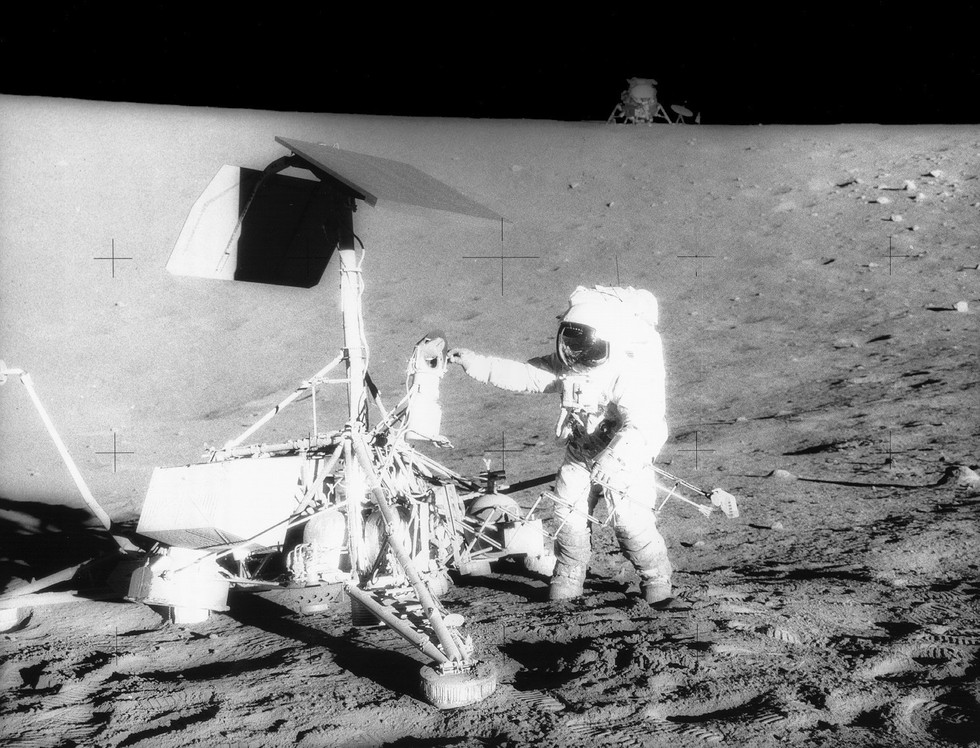

The Surveyor landings helped with Apollo in several ways, Rennilson said: they showed that a heavy spacecraft could sit on the lunar surface and they practiced the controlled landings (using retrorockets) needed for lunar exploration. Surveyor's pictures from orbit also targeted potential Apollo lunar landing sites, giving the mission planners crucial information to help the astronauts land safely.

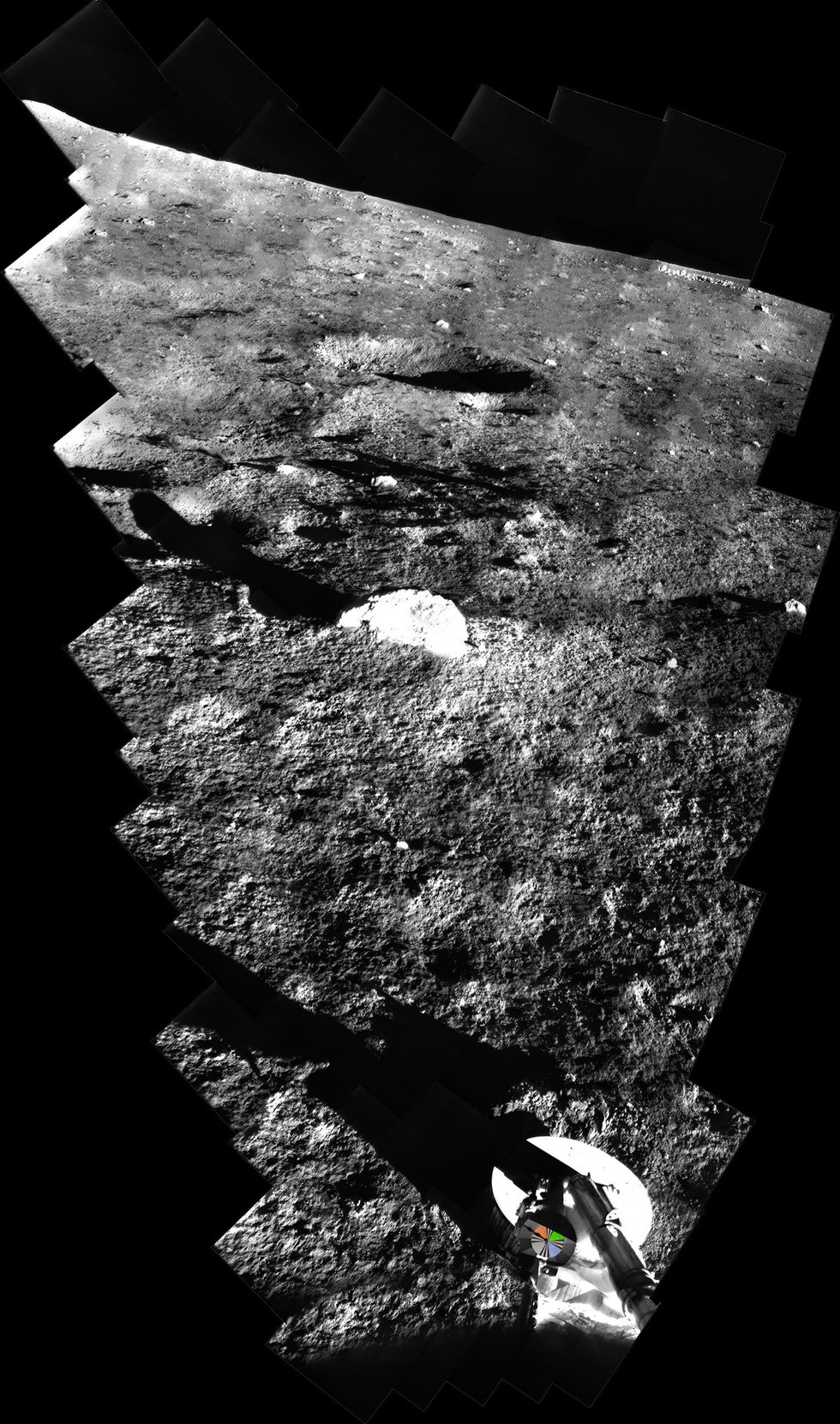

Besides the first landing of Surveyor, Rennilson says the Surveyor 7 mission was another highlight because it targeted the rugged lunar highlands instead of the safer seas (maria) where other missions landed. That mission landed on the rim of the immense Tycho crater that pops out even in binocular views of the moon.

"We went a little bit north of that center of that crater on to the rim, and when we landed of course we looked around and there were a lot of rocks," Rennilson said, adding that they used the fragments to help them calculate distance on the featureless surface.

Rennilson's later work included helping plan the moonwalks (extra-vehicular activities) of Apollo astronauts between 1969 and 1972, then moving back to San Diego to work for Gamma Scientific. He also created his own company that he ran for 13 years before it was sold. Rennilson continues consulting work to this day, and remains active in watching new lunar exploration programs. He hopes that the levitating dust will be proven by another mission soon.

"It's a wonderful thing to talk with people (and say) here is something we see on the moon. Our hypothesis can only be proven by somebody landing again and taking some pictures," Rennilson said.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.