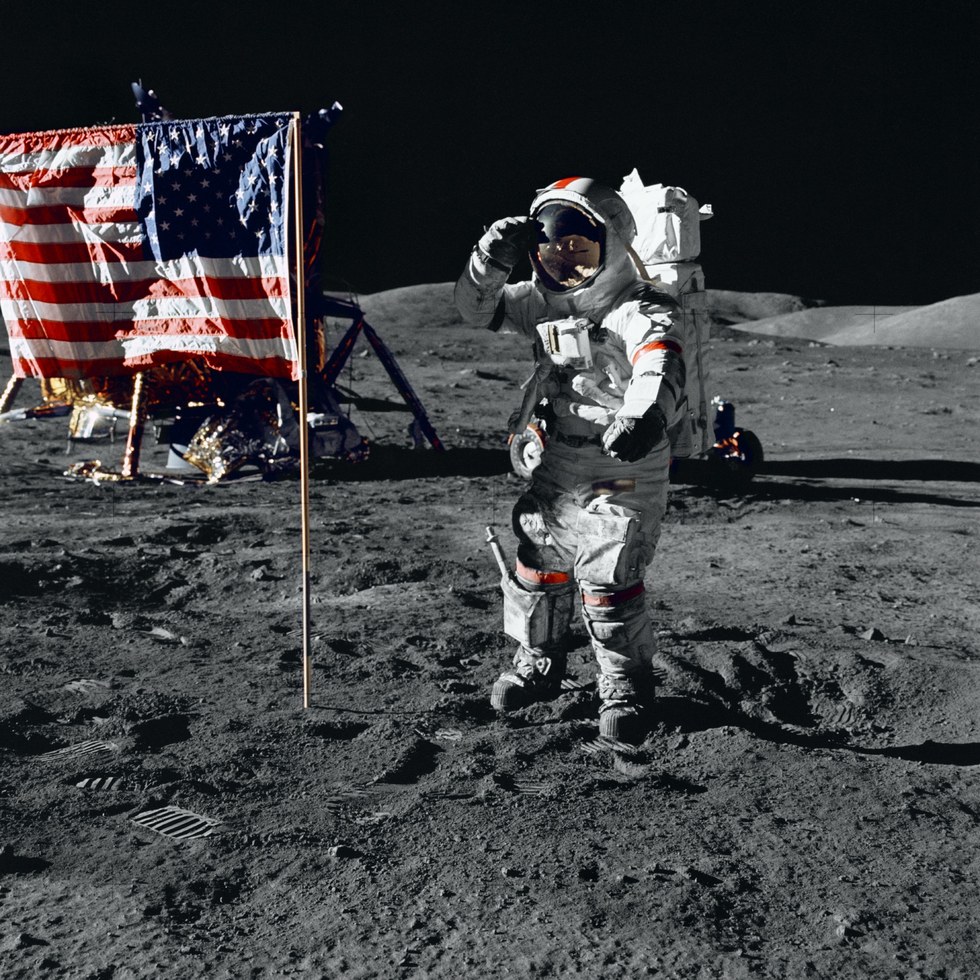

Remembering Apollo 17's Gene Cernan — the Last Man to Walk on the Moon

Gene Cernan, the last human to walk on the moon, died last week at age 82. The naval aviator joined NASA in 1963 and remained with the agency for over a decade, flying three times in space. He is one of only three people to travel to the moon twice and one of only 12 people to walk upon its surface. Here are some of the most memorable photographs from his last mission, Apollo 17, in 1972.

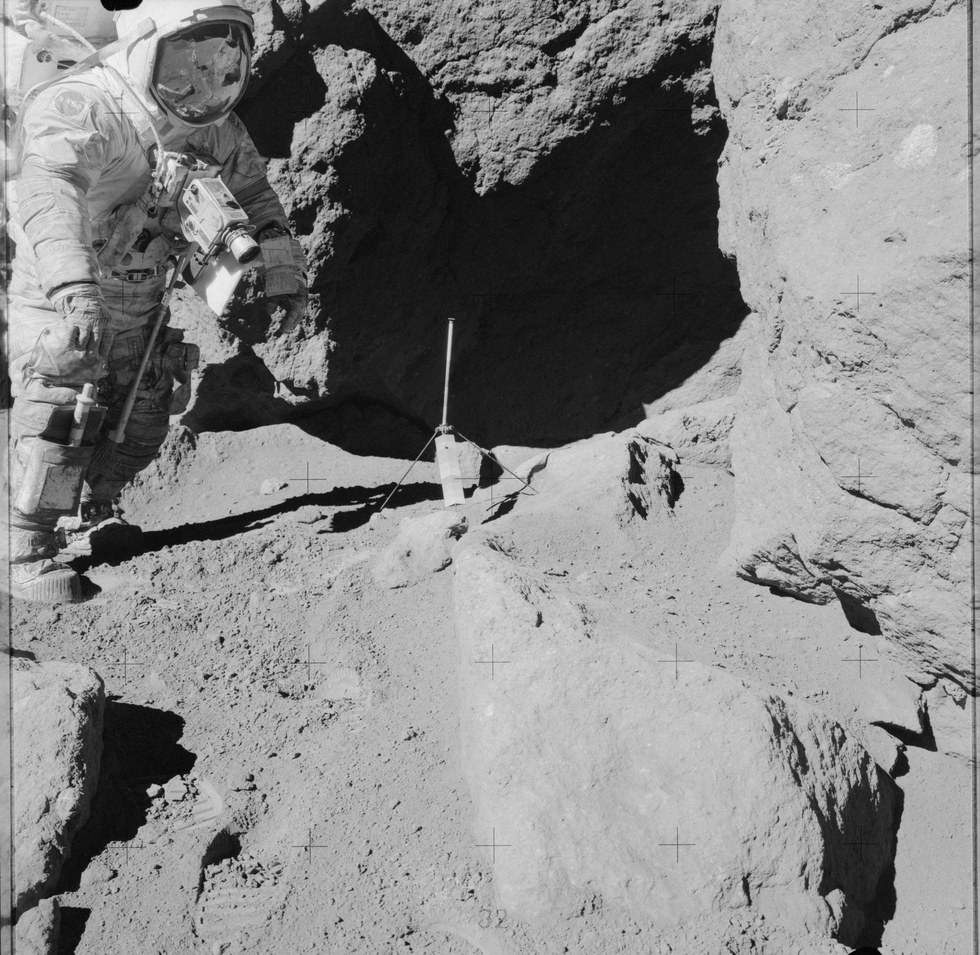

Liftoff of the Apollo 17 mission, aboard a powerful Saturn V rocket, took place early in the morning on Dec. 7, 1972. On board were commander Gene Cernan — a veteran of the Gemini program and moon-orbiting mission Apollo 10 — as well as two rookies, lunar module pilot Harrison (Jack) Schmitt and Ron Evans. Apollo 17 targeted a landing in the lunar Taurus-Littrow valley and had two main geological objectives, according to the Lunar and Planetary Institute: to sample material in the highlands that were older than rocks created from an impact in nearby Mare Imbrium, and to see if volcanism had happened in the valley.

Apollo 17 was the sixth Apollo mission to land on the moon, and the last to see humans walk on the surface. Though there are no firm plans from any space agency to return humans to the moon in the near future, robotic exploration of the moon (mostly in orbit) has continued, particularly as scientists discovered evidence of water ice on its surface. NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has also taken high-resolution imagery of all the Apollo landing sites, including Apollo 17.

Cernan and Schmitt, the first scientist-astronaut to fly in space, landed on the surface in the lunar module Challenger. Evans stayed in lunar orbit in the command module America. (America is on display at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston, while Challenger's ascent stage impacted the moon as planned after the mission was finished.)

RELATED: Eugene Cernan, Last Man to Walk on the Moon, Has Died at 82

"There's no way I'm going to go all the way to the moon, particularly for a second time, and let a computer land me on the moon," Cernan, who landed Challenger, said in a 2007 oral interview with NASA. "The arrogance of a pilot, particularly naval aviators, is too great to allow that to happen. Nobody ever landed on the Moon other than with their own two hands and brain and eyeballs and whatever. Computer-assisted, yes. Got a lot of information. We got help from a lot of sources."

While the first lunar missions relied on the astronauts' feet, the lunar rover allowed missions to range further from the lunar module, although NASA was careful to watch astronauts' oxygen supplies so they could still walk back even if the rover stopped operating.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On Apollo 17, Cernan accidentally ripped off one of the lunar rover fenders after inadvertently catching a rock hammer on it. "We had to fix it," Cernan said in a NASA interview in 2008. "Because otherwise a rooster tail of dust would really, really be bad. And the bottom line, we came up with a fix where we took some geology maps and taped them together in the spacecraft with, of all things, duct tape. And then took a couple clamps from lights we had in the lunar module and clamped them to what was left of the fender. And it stopped the dust."

In his 1999 autobiography "Last Man On The Moon", Cernan wrote about the strange nature of the Apollo program's timing. "President Kennedy reached far into the twenty-first century, grabbed a decade of time, and slipped it neatly into the 1960s and 1970s," he wrote. "Logic dictates that after Mercury and Gemini, we should have proceeded to build the shuttle, then an orbiting space station, and only then sought the Moon. It was as if our young nation had chosen to never again cross the Mississippi River after Lewis and Clark discovered the Northwest Passage."

A dirty and tired Cernan is photographed here after the second of his three extravehicular activities (moonwalks) on the moon. Behind the camera was Schmitt, who used a 70 mm Hasselblad camera to capture this image. The three moonwalks comprised more than 22 hours all told, and yielded nearly 250 pounds of moon rocks that are still being analyzed by scientists today.

RELATED: After Cernan, Only Six Apollo Moonwalkers Remain

"Science and technology got me there, but when I got there and I looked back home at the Earth, science and technology could not explain what I was seeing nor what I was feeling," Cernan said in a 2007 interview with NASA. "You look at the Earth, and it very majestically yet mysteriously rotates on an axis you can't see, but must be there."

The ascent stage of Apollo 17's Challenger spacecraft leaves the moon forever, as captured by a remotely operated camera on a nearby lunar rover. Below it is the descent stage, which remained behind. Cernan and Schmitt left the moon on Dec. 14, 1972 to rejoin their crewmate Evans in the command module orbiting the moon.

A plaque left behind on the moon reads: "Here Man completed his first explorations of the Moon, December 1972 AD. May the spirit of peace in which we came be reflected in the lives of all mankind." It is signed by Cernan, Evans, Schmitt and then-U.S. president Richard Nixon.

WATCH VIDEO: Why Are There No Stars In The Apollo Photographs?

Originally published on Seeker.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.