The Sun's Got Waves — Like Earth's Atmosphere

Most of the time, the sun and the Earth couldn't be more different: One is a star, the other a planet; the sun is made of plasma and fuses hydrogen to helium, while the Earth is a solid body heated by radioactive decay (and the sun's rays). But the two bodies' atmospheres share something in common: A type of wave that undulates through Earth's skies may have an analogue in the body of the sun, according to a new study.

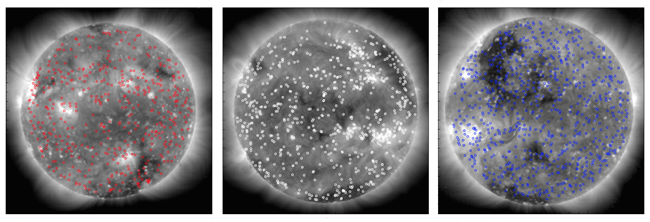

NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) and Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory (STEREO) mission, which included two spacecraft orbiting the sun, spotted a type of wave called a Rossby wave on the sun's surface. This type of wave occurs in rotating fluids, such as atmospheres and oceans. The findings could help link several phenomena tied to the sun's magnetic field, such as the source of sunspots, the length of time those spots last and the origin of the 11-year solar-activity cycle.

Rossby waves also occur in Earth's atmosphere and oceans, and they help to dictate the planet's weather, researchers said in a statement. [Anatomy of Sun Storms & Solar Flares (Infographic)]

"The discovery of Rossby-like waves on the sun could be important for the prediction of solar storms, the main drivers of space weather effects on Earth," Ilia Roussev, program director in NSF's Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences, said in the statement. "Bad weather in space can hinder or damage satellite operations and communication and navigation systems, as well as cause power-grid outages leading to tremendous socioeconomic losses. Estimates put the cost of space weather hazards at $10 billion per year."

In the air on Earth, Rossby waves cause meandering paths in the jet stream, a narrow but powerful stream of wind that forms high in the atmosphere. Sometimes, the result is a cold snap in one area while the temperatures are relatively balmy nearby, because the jet stream separates the warmer, temperate-zone air from the cold, Arctic atmosphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

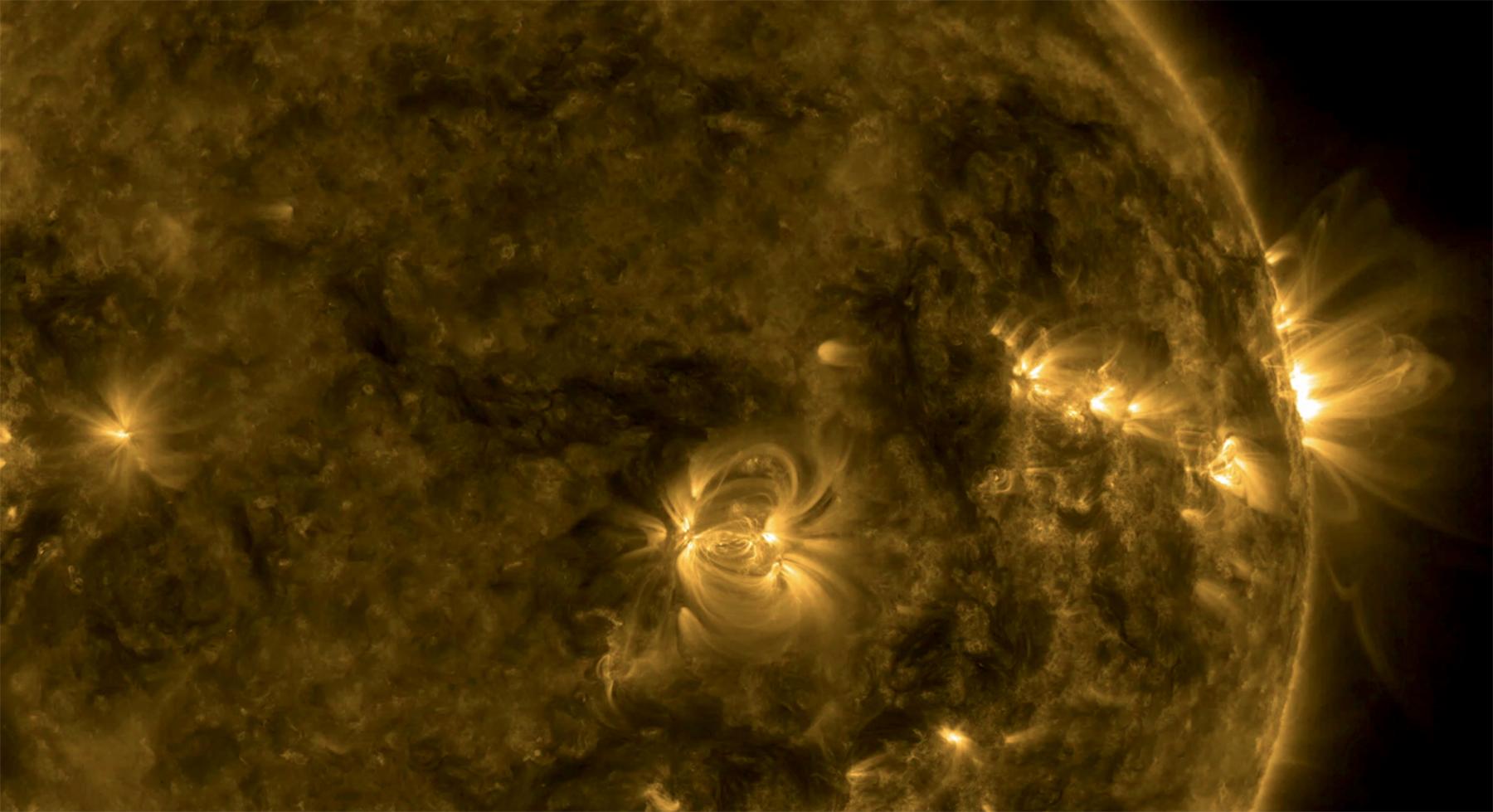

Unlike the Earth, the sun doesn't have a solid surface. Instead the star's surface is a strongly magnetized ocean of hot plasma, so it can behave like a fluid. The sun rotates as well, about once every 28 days. Therefore, Rossby waves should appear as areas of magnetic activity that move across the face of the sun — but until recently nobody had found hard evidence for them, researchers said in the statement.

NASA's solar observatories were finally able to provide the clues. From 2011 to 2014, the SDO and STEREO missions got a full, 360-degree picture of the surface of the sun, called the photosphere. Ground control lost contact with the STEREO spacecraft in 2014, but the two missions together managed to get enough data that researchers could get a picture of the large-scale movement of magnetized plasma across the surface — and see the telltale Rossby wave pattern, the study said.

In a statement NCAR said the observations advanced human knowledge, but more studies will be needed before scientists can predict solar weather in the way they do its Earthly counterpart.

"To connect the local scale with the global scale, we need to expand our view," NCAR scientist Scott McIntosh, lead author of the paper, said in the statement. "We need a constellation of spacecraft that circle the sun and monitor the evolution of its global magnetic field."

The study appeared in the journal Nature Astronomy on March 27.

You can follow Space.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.