June full moon 2025: The Strawberry Moon hides red star Antares

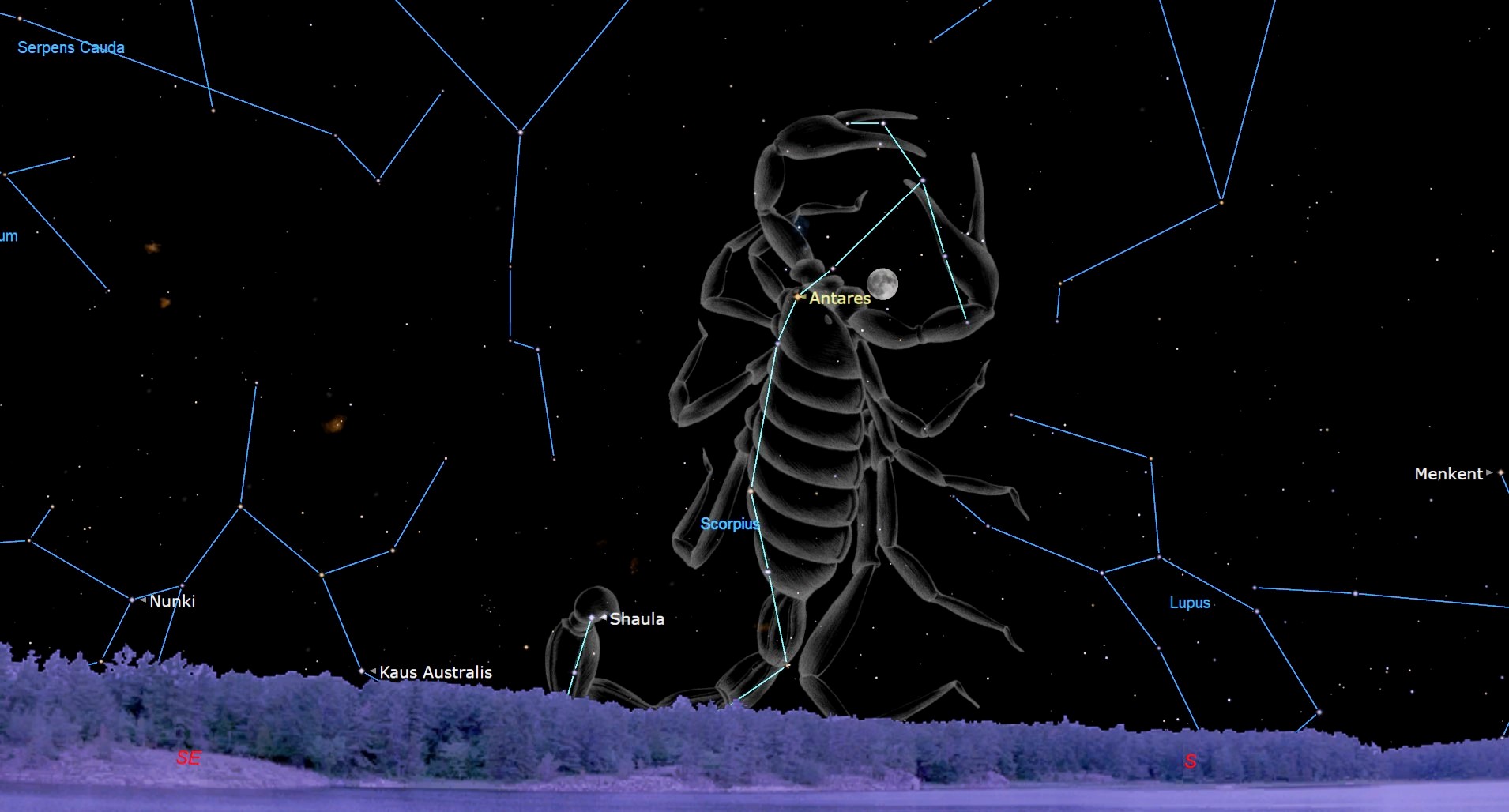

The full moon of June 2025, the Strawberry Moon, will pass in front of the red supergiant star Antares the day before the full moon in an event known as an occultation.

The full moon of June, also called the Strawberry Moon, will occur on June 11. A day prior (June 10) Australians and New Zealanders will see the moon occult Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius, the Scorpion.

The exact moment of full moon occurs at 3:44 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time (0744 UTC), according to the U.S. Naval Observatory. The moon's occultation of Antares won't be visible from New York. North American sky watchers will see a very close pass of the moon just to the south of ("below") Antares.

In New York City, moonrise is at 9:24 p.m. EDT on June 11; sunset is at 8:27 p.m. on that day. Full moons happen when the moon is on the opposite side of the Earth from the sun. On the night side of Earth, we see a fully-illuminated moon; since full moons are reckoned relative to the positions of the moon and Earth the timing of a full moon is the same all over the world, with differences due to one's time zone (longitude). The lineup of sun, moon and Earth is called a syzygy – a Greek-derived word.

Looking for a telescope to see the full moon up close? The Celestron NexStar 4SE is ideal for beginners wanting quality, reliable and quick views of celestial objects. For a more in-depth look at our Celestron NexStar 4SE review.

The time between each syzygy is the lunar month; but it is actually a bit longer than the time it takes the moon to circle the Earth. The time it takes the moon to complete a circuit of the Earth is called the siderial period and is 27.3 days. The time between syzygies is called the synodic period and is 29.5 days – the latter being what we humans use as the lunar month because it is the time between successive phases of the moon. The difference is because in 27 days the Earth itself has moved in its orbit, so the moon has to go a little further in order to be in a straight line with the sun and Earth.

Summertime full moons tend to be lower in the sky for Northern Hemisphere sky watchers, because the part of the moon's orbit opposite the sun is below the celestial equator; the moon is effectively in the same place a wintertime sun would be. For example, in New York City, on the night of June 10-11, the moon's highest altitude in New York City is only 20 degrees (reached at 12:47 a.m. June 11). In a Southern Hemisphere city such as Cape Town, where the seasons are flipped, the moon (which reaches full phase at 9:44 a.m. local time June 11) the moon is 75 degrees high at 12:03 a.m. on June 12.

Occultation of Antares

The lunar occultation of Antares will be visible in Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the South Pacific; the eastern limit is Easter Island and the western limits are the western coast of Australia and western Indonesia. Observers in other regions will see the moon make a close pass to Antares.

On the very western side of the region where the occultation is visible, it occurs in twilight and only the reappearance of Antares will be readily seen. For example, in Perth, Western Australia, Antares disappears at 5:39 p.m. Australian Western Standard Time on June 10, and even though the moon and Antares are both above the horizon (moonrise is at 4:13 p.m.) the sky will still be quite light as sunset is at 5:18 p.m. Antares reappears at 5:49 p.m., just a few minutes after civil twilight ends at 5:45 p.m. Antares will appear to duck behind the upper right quadrant of the moon; it will be hard to make out the star against the background sky with the unaided eye.

Further east the occultation is later in the evening and thus easier to see. In Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, Antares disappears at 7:07 p.m. local time; the moon will be about 27 degrees above the east-southeastern horizon. Reappearance is at 7:35 p.m. Antares will disappear and reappear on the lower left side of the moon.

In Sydney, where the moon will be 40 degrees high in the east, Antares will disappear behind the lower right quadrant of the moon at 7:25 p.m. local time, and reappear at 8:40 p.m. from the upper left quadrant.

New Zealanders will see the occultation much higher in the sky; in Auckland, disappearance is at 10:03 p.m. New Zealand Standard Time, and reappearance is at 11:27 p.m. The moon will be 68 degrees above the northeastern horizon, and Antares will disappear behind the right (eastern) side of the moon and reappear from the left (western) side.

Visible Planets

If you can't observe the Antares occultation, the full moon night still offers other targets; on the evening of June 11, from the latitudes of New York City, Chicago or Sacramento, Mars will be visible in the evening after sunset (which is at 8:27 p.m. local time in New York). By about 9 p.m. the sky will be just dark enough to see it; in New York City the planet sets at 12:23 a.m. on June 12. In the evening Mars will be in the southwest, about 36 degrees above the horizon. One way to spot it is to look to the left of Mars, which is distinctly reddish; there one will see Regulus, the alpha star of Leo the Lion, which is much more yellow-white.

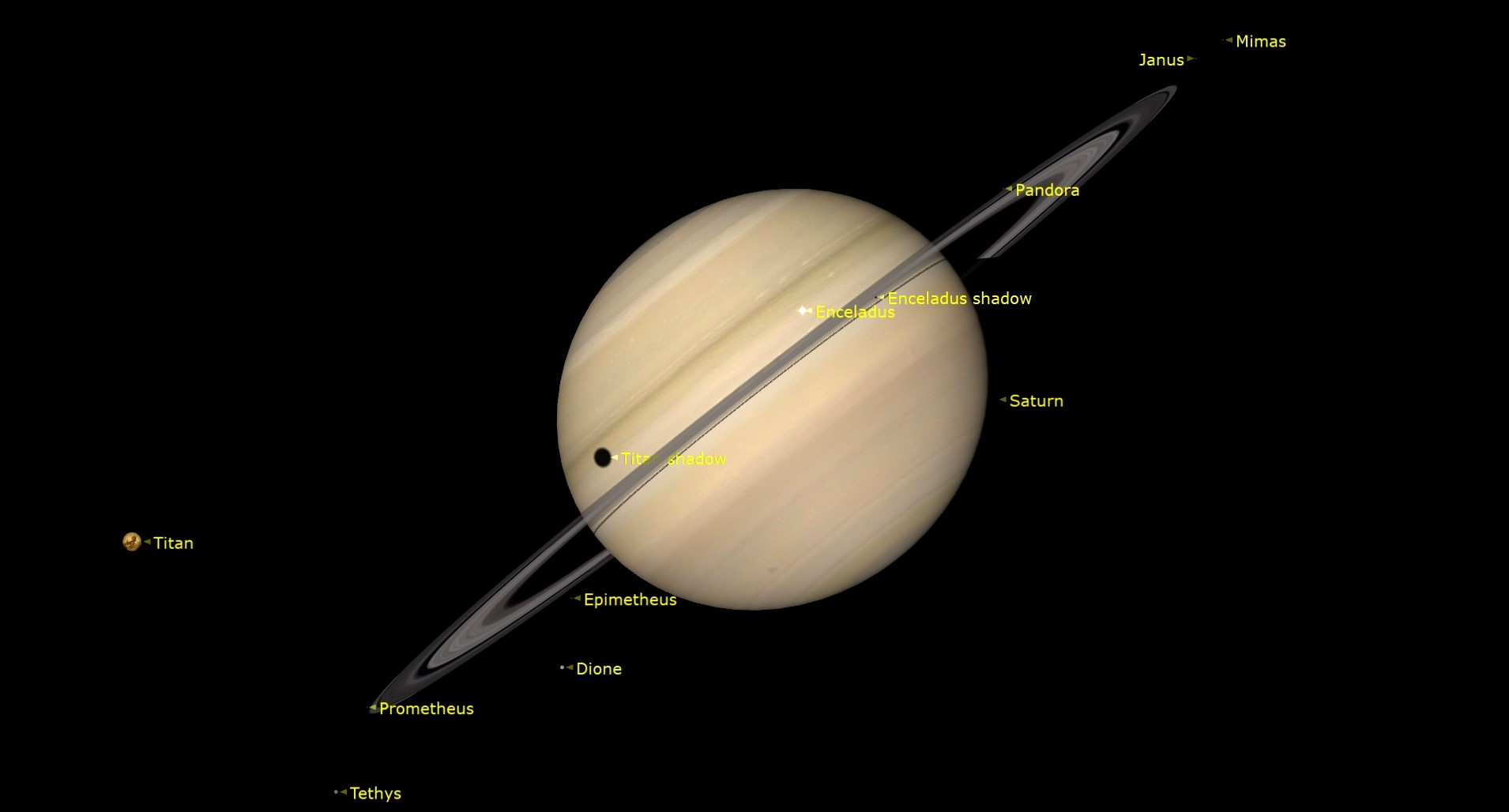

Saturn is the next to come up – the planet rises at 1:42 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time on June 12 in New York City. By sunrise (at 5:24 a.m.) it is 37 degrees high in the southeast. As Saturn climbs one will see Venus, which rises at 3:09 a.m. By 4:30 a.m., as the predawn twilight stars, one will see Saturn, 30 degrees high, to the right of Venus, which is almost due east at 14 degrees; it will be the brightest object besides the moon.

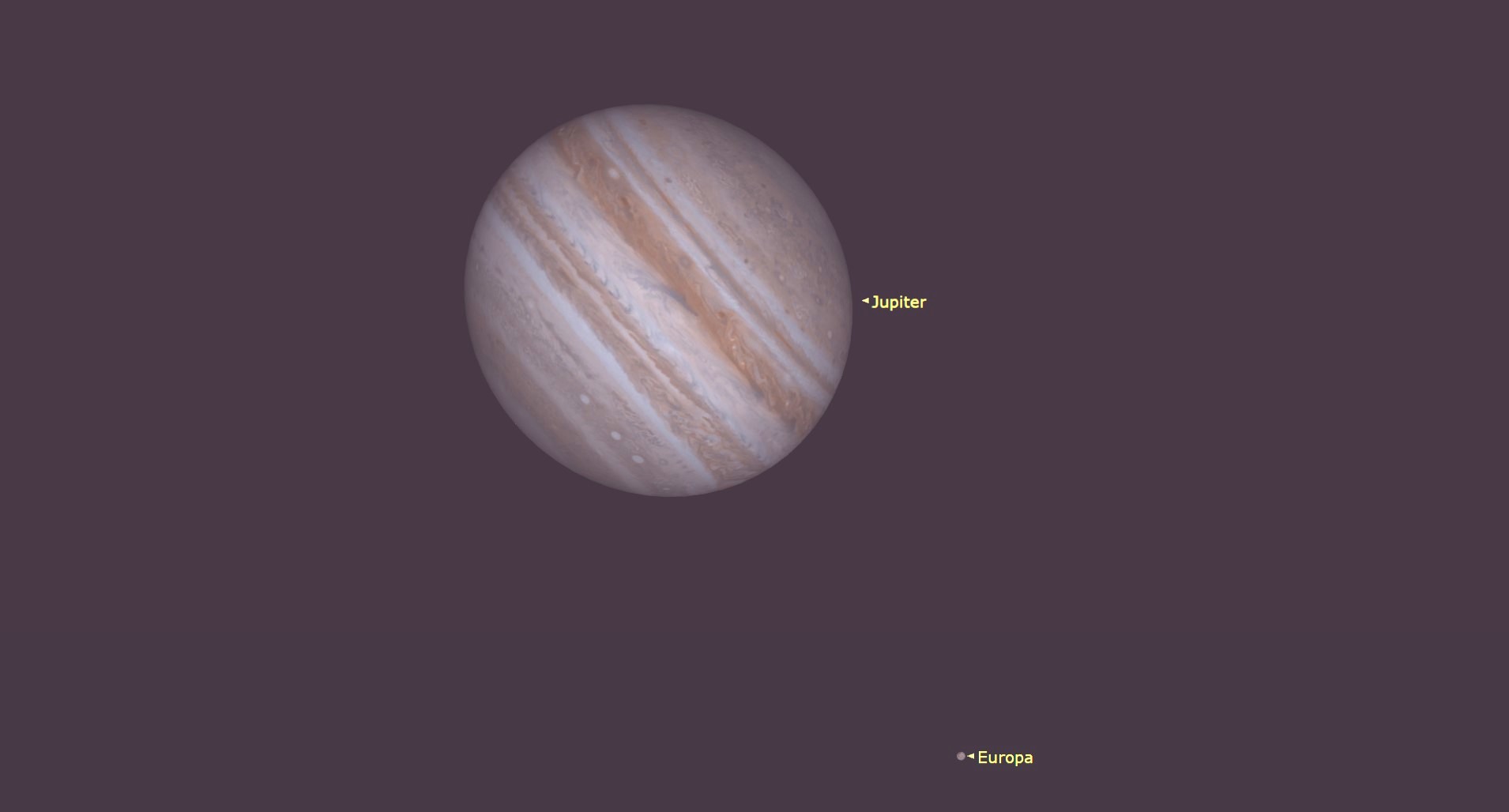

Mercury and Jupiter are both above the horizon at sunset on June 11, but neither is high enough to observe easily in the glare. It is just possible to catch Mercury if one has a flat horizon (as one might have over water) and perfectly clear conditions, but the planet an hour after sunset on June 11 is only 5 degrees high in the west.

For those watching the sky from south of the Equator, Mars will appear as high in the sky as it does in New York after sunset, but since the sun sets earlier the planet is visible longer. In Santiago, Chile, Mars will be about 40 degrees high in the northwest at 6:30 p.m. local time; sunset there is at 5:41 p.m. Mars sets at 10:45 p.m. From the mid-southern latitudes, the sky is "upside down" – so Mars appears to be below Regulus, rather than to the right.

As in the Northern Hemisphere, Saturn rises next, at 1:20 a.m. June 12 in Santiago, and Venus rises at 4:05 a.m. Sunrise is not until 7:44 a.m., meaning that by about 6:30 a.m. Saturn will be 55 degrees high in the northeast, with Venus a full 26 degrees above the northeastern horizon.

Observing prospects for Mercury and Jupiter are no better than in the Northern Hemisphere; both are lost in the glare of the sun as it sets.

Constellations

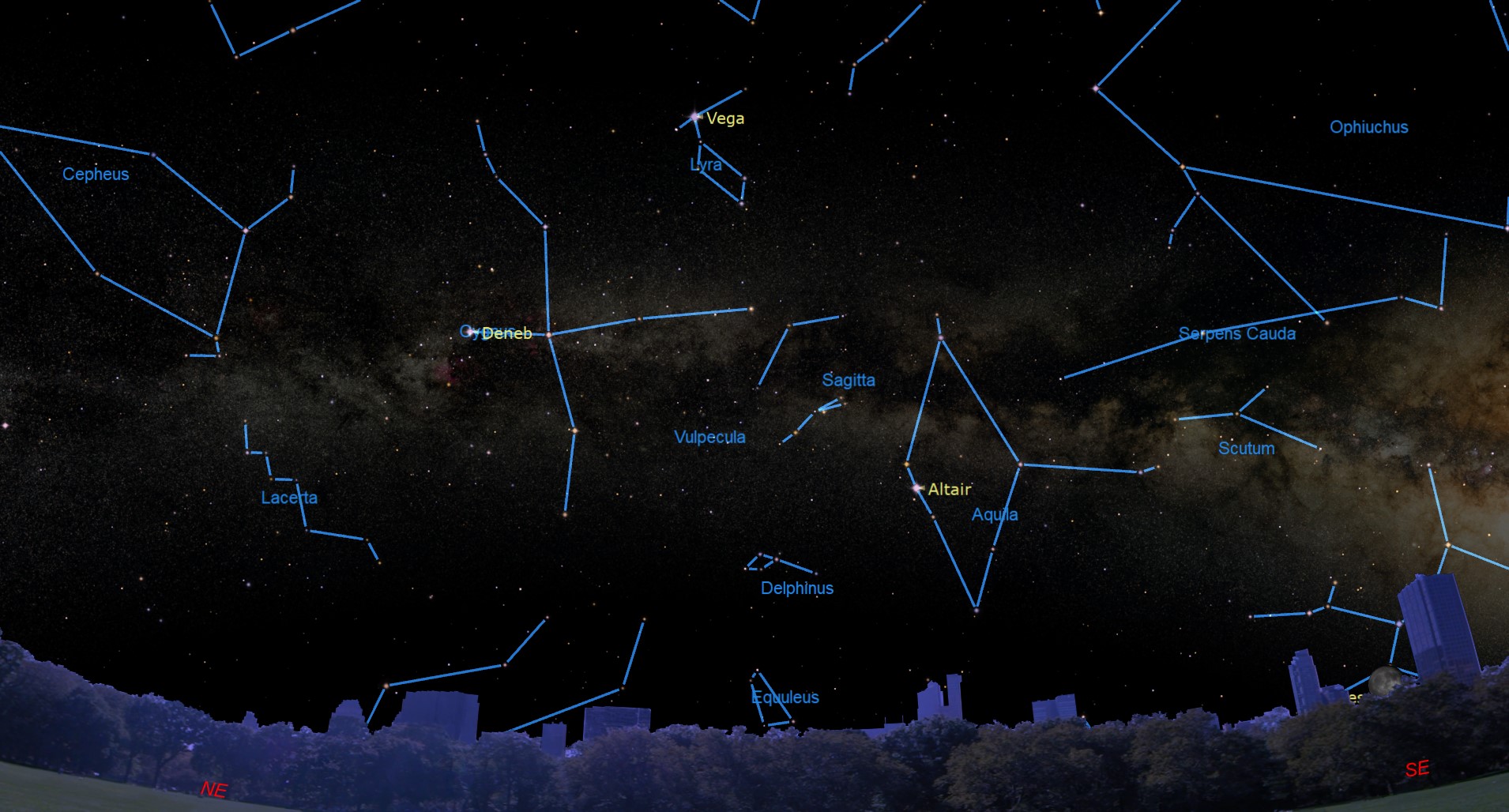

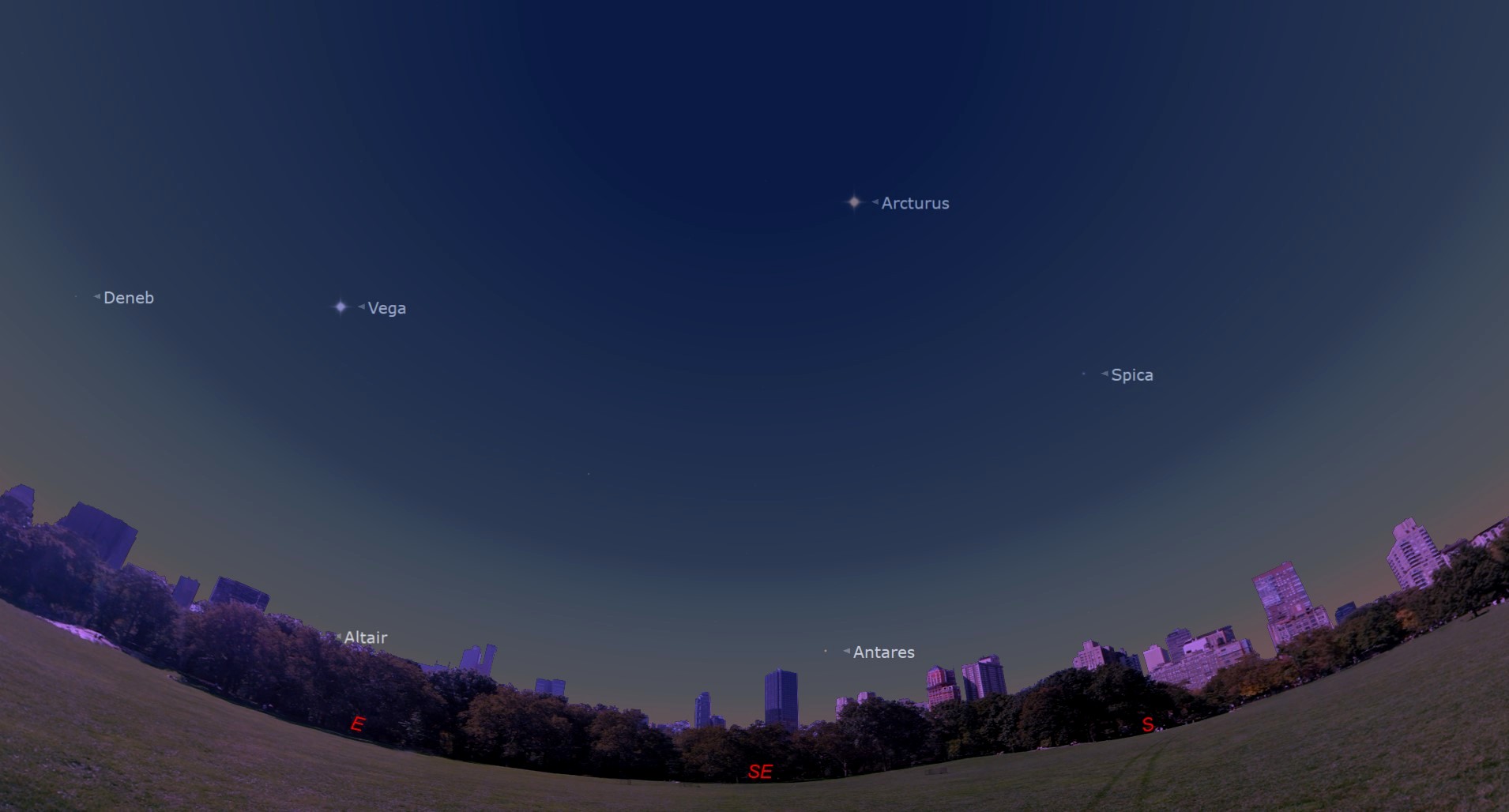

Among stars, by 10 p.m. in the mid-northern latitudes, one will see the summer constellations most prominently; looking to the east, above and to the right of the moon as it rises in the southeast, one can see Antares, the heart of Scorpius the Scorpion. Turning left from the moon due east one can see the Summer Triangle, an asterism consisting of Vega, or Alpha Lyrae, Deneb (Alpha Cygni) and Altair (Alpha Aquilae).

Vega is the highest of the three; at about 10 p.m. it is 43 degrees high in the east (almost halfway to the zenith). Go down and to the left and the next bright star one sees – it will be about half as high as Vega – is Deneb, the tail of Cygnus the Swan. Look to the right (imagine a right triangle with Deneb at the 90 degree corner) and one will see Altair, which will be a few degrees higher than the full moon.

Turn left of Deneb and you are facing north; Deneb is almost exactly northeast. The Big Dipper will be high in the sky – the end of the handle will be almost directly overhead and to the left, with the bowl downwards from there, almost as though one were pouring liquid out to the right. One can use the "pointers" of the Dipper's handle to find Polaris, the Pole star, and if one continues towards the right and downward one touches the "W" shape of Cassiopeia, the Queen, which will be close to the horizon. Cassiopeia is one of the constellations that from mid-northern latitudes is circumpolar; it never actually sets.

One can use the handle of the Big Dipper to "Arc to Arcturus", the brightest star in Boōtes, the Herdsman, which will be some 67 degrees high in the south. Arcturus is recognizable because it looks slightly reddish or orange. Look right of Arcturus (eastwards) and one can see a bright circlet of stars, this is Corona Borealis, the Northern Crown. Keep going right – towards Vega – and one encounters a group of four medium-bright stars in a square, which is the "keystone" – the center of the constellation Hercules.

Continuing the "arc" from Arcturus ends at Spica, the alpha star of Virgo, and turning to the right (towards the south) one sees Leo, the Lion. To the left is Scorpius, the Scorpion and Antares.

In the mid-southern latitudes, the sky will be dark by 7 p.m. and one will see the moon in the east, with Antares (if one isn't in the zone where the occultation is visible) above it and to the left. Looking to the west, one can see Sirius, the brightest star in the sky and a prominent feature of Northern Hemisphere winter skies; from the latitude of Santiago or Cape Town it sets by about 9 p.m. If one turns southwards from Sirius (to the left) one sees Canopus, nearly as bright as Sirius, almost due southwest about 31 degrees high.

Looking almost due south and two thirds of the way to the zenith one can spot the Southern Cross, which points to the southern celestial pole (though there is no equivalent of Polaris to mark it). Below and to the left of the Cross are Hadar and Rigil Kentaurus, or Alpha Centauri; Hadar is the higher of the two.

How the Strawberry Moon got its name

In the Old Farmer's Almanac, the full moon of June is called a Strawberry Moon, as the berries appear in the summer months in the northeastern parts of North America. The term Strawberry Moon is also used by the Ojibwe people, whose traditional lands were in the northern plains and the Great Lakes region. But the Woodland Cree, who live in northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan, call the June lunation the Egg Laying Moon, as that is when waterfowl in the region lay their eggs.

In the Chinese lunar calendar the June full moon is in the fifth month, called Púyuè, the Sweet Sedge Month; it is also the month of the Dragon Boat festival, an important holiday in mainland China.

For some regions of India, the June full moon is the festival of Kabir Jayanti, in the Hindu lunar month of Jyēṣṭha. The holiday celebrates Kabir, a mystic and poet, who was known as a critic of both Hindu and Islamic ritual and social reformer.

In the Southern Hemisphere, the Māori described the lunar month of Hongonui, which occurs from June to July, as "Man is now extremely cold and kindles fires before which he basks" according to the Encyclopedia of New Zealand – June being the middle of the austral winter.

You can prepare for the next full moon with our guide on how to photograph the moon. If you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography to make sure you're ready for the next eclipse.

And if you're looking for binoculars or a telescope to observe the moon, check out our guides for the best binoculars and best telescopes.

Editor's note: If you snap an image of the full Strawberry Moon and would like to share it with Space.com's readers, send your photo(s), comments, and your name and location to spacephotos@space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.