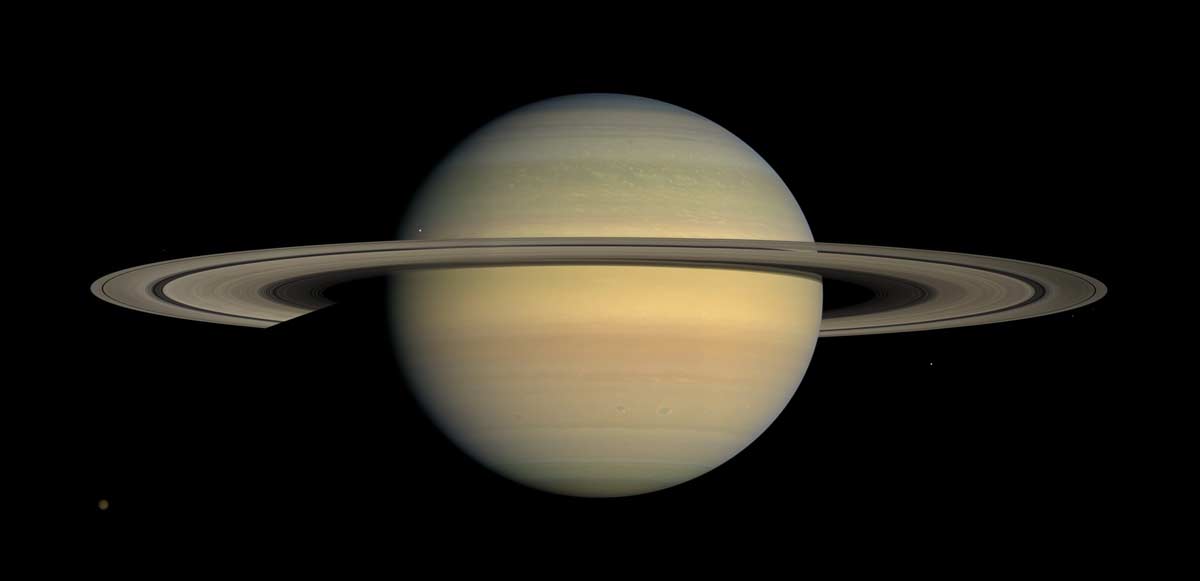

Cassini Probes Last Saturn Mysteries 1 Month from Demise

The end is nigh for NASA's trailblazing Cassini mission to Saturn as the veteran spacecraft enters its final month in orbit. The probe will burn up like an artificial meteor in the gas giant's upper atmosphere on Sept. 15, ending a 13-year odyssey at the ringed planet.

As the concluding phase of its "Grand Finale," the spacecraft has begun a series of daring, ultraclose passes of the planet to end its mission in style. Cassini's current orbit takes the spacecraft high over the planet's poles and through the gap between the planet's innermost ring and upper atmosphere — close passes that will ultimately end with Cassini careening deep into Saturn's upper atmosphere.

"It's very bittersweet," said Jo Pitesky, Cassini project science system engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. "But [Cassini's] doing what she was built for. She's going on to explore and to see the mission acquire great science and not go out with a whimper. … It's tremendously fulfilling." [Cassini's 'Grand Finale' at Saturn: NASA's Plan in Pictures]

On Monday (Aug. 14), Cassini made its closest flyby of Saturn yet, swooping just 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) above the planet's cloud tops. At this distance, the spacecraft's cameras can see atmospheric features just 16 miles (25 km) across, 100 times smaller than it could see at any time before the Grand Finale phase of the mission, NASA officials wrote in a statement. But as Cassini gets closer, it will also be able to take direct measurements of the atmosphere, ultimately becoming an atmospheric probe itself.

"Cassini will become the first Saturn atmospheric probe," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL, said in the same statement. "It's long been a goal in planetary exploration to send a dedicated probe into the atmosphere of Saturn, and we're laying the groundwork for future exploration with this first foray."

"Sniffing" distance

But before Cassini takes its final, Sept. 15 plunge, and with time of the essence, science operations are in overdrive to gather as many measurements as possible during these unprecedented close passes. This will hopefully help explain some perplexing mysteries that continue to puzzle mission scientists.

During Monday's close approach, Cassini made "the first in-situ composition measurement of Saturn's upper atmosphere," Pitesky told Space.com, adding that she hopes that each of the four successive orbits will encounter particles from the planet's atmosphere so that Cassini's Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) can measure direct samples.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Indirect measurements of the constituents of Saturn's atmosphere, rings and magnetosphere have been made in the past. But during close passes like Monday's dive, Cassini can directly study the tenuous gases leaking into space from the upper atmosphere, providing a unique opportunity to build a better picture as to what chemicals the atmosphere contains, Pitesky said.

"To actually get in there and take a good, long 'sniff' and sample the atmosphere directly, that's going to be our first chance to see that when we get the data back," she said.

Depending on how much of Saturn's atmosphere Cassini encounters, Pitesky added, mission managers may decide to carry out "pop-up" or "pop-down" maneuvers — using the spacecraft's thrusters to slightly adjust its orbital speed depending on how much drag the spacecraft experiences on each pass. This is done to optimize the probe's position to measure samples. [Latest Saturn Photos from NASA's Cassini Orbiter]

Grand Finale mysteries remain

Cassini's Grand Finale began on April 22 as the spacecraft began its first dive toward the gap between Saturn and the planet's innermost ring. While planning this exciting phase of the mission — a phase that would see the spacecraft fly where no spacecraft had flown before — scientists were concerned that the probe might encounter a cloud of dust particles, or maybe even larger debris. Hitting any debris at high speed could have caused serious damage to the spacecraft. So, as a precaution, mission planners positioned Cassini's large, high-gain antenna in the direction of travel to act as a "high-tech umbrella" and shield against direct hits, said Pitesky.

"One of the biggest surprises was what we saw [during the first dive], when project managers were concerned that the environment in the upper levels of the atmosphere and the inner edges of the rings were going to be far more dusty than expected," Pitesky added. Instead, as the planned 22 orbits commenced, each taking approximately 6.5 days to complete, there was surprise at how few dust particles the mission encountered during each dash through the ring gap, she said.

"It is a mystery why that area is so clear," Pitesky said.

It was hoped that flying Cassini so close to Saturn might help solve another mystery: whether Saturn's magnetic pole has what scientists call an offset.

The planets in the solar system that possess global magnetic fields, including Earth, tend to exhibit an offset between the axis of rotation and the axis of magnetic pole. According to theory, to keep the metallic hydrogen layer inside Saturn churning, there needs to be an offset to generate the magnetic field in the first place. But with only four orbits to go, and after multiple close approaches to the planet, Cassini's instruments have not been able to detect an offset.

That's a problem if scientists want to learn exactly how long a day is on Saturn, because when trying to precisely gauge the rotation rate of a gas giant, you need to measure the magnetic offset. But in the case of Saturn, the magnetic axis seems to be parallel with the axis of rotation, so there's no accurate way to measure the precise length of a Saturn day.

"We still don't know the length of a day on Saturn, and we don't know why Saturn is being so coy about it," said Pitesky. "There's something very interesting going on in the interior of Saturn to keep us from … seeing a tilt to the magnetic field's pole" when the probe is so close to the planet.

A Titanic kiss goodbye

On Sept. 11, Cassini will use the gravity of Saturn's huge moon Titan to slow its orbital speed — like a large "pop-down" maneuver — thereby slightly bending its orbit closer to Saturn, NASA officials said in a statement. During its mission, Cassini has become intimately familiar with this moon, discovering vast seas of liquid methane and ethane under its thick atmosphere. This final gravitational "kiss" with Titan will send the spacecraft on a trajectory to burn up in Saturn's atmosphere four days later.

Whether Saturn shares any more of its secrets before Cassini's mission ends remains to be seen, but the spacecraft's fate is sealed: It's going to crash into Saturn with a little help from Titan in only four weeks' time.

Follow Ian O'Neill @astroengine. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.