Astronaut John Young, Who Walked on the Moon and Led 1st Shuttle Mission, Dies at 87

John Young, NASA's longest-serving astronaut, who walked on the moon and flew on the first Gemini and space shuttle missions, has died.

The first person to fly six times into space — seven, if you count his launch off of the moon in 1972 — and the only astronaut to command four different types of spacecraft, Young died on Friday (Jan. 5) following complications from pneumonia.. He was 87.

"NASA and the world have lost a pioneer," said NASA acting administrator Robert Lightfoot in a statement on Saturday (Jan. 6). "John Young's storied career spanned three generations of spaceflight; we will stand on his shoulders as we look toward the next human frontier."

"Young was at the forefront of human space exploration with his poise, talent, and tenacity. He was in every way the 'astronaut’s astronaut,'" Lightfoot said. [Astronaut John Young Remembered in Photos]

Selected alongside Neil Armstrong and Jim Lovell with NASA's second group of astronauts in 1962, Young flew two Gemini missions, two Apollo missions and two space shuttle missions. He was one of only three astronauts to launch to the moon twice and was the ninth person to step foot on the lunar surface.

In total, Young logged 34 days, 19 hours and 39 minutes flying in space, including 20 hours and 14 minutes walking on the moon.

"I've been very lucky, I think," Young said in a NASA interview in 2004, when he retired from the space agency after 42 years.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Young made the first of his six missions as the pilot on the maiden flight of Gemini, NASA's two-seater spacecraft. Flying with original Mercury astronaut Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Young launched on the nearly five-hour Gemini 3 mission on March 23, 1965, putting the new vehicle through its paces while also taking a bite or two from a later infamous corned beef sandwich that he smuggled aboard the flight.

Gemini 3 "was a truly excellent engineering test flight of the vehicle," Young wrote in his 2012 memoirs, "Forever Young."

Young commanded his second spaceflight, Gemini 10, in July 1966. The three-day mission climbed to more than 400 miles (760 kilometers) above Earth to measure the risk posed by radiation, conducted the program's first double rendezvous with two Agena target vehicles and included two spacewalks by pilot Michael Collins.

On the Apollo 10 mission in May 1969, Young became the first person to orbit the moon alone. During the flight, which was a full-up dress rehearsal for the first lunar landing two months later, Young remained on board the command module "Charlie Brown" while his crewmates, Thomas Stafford and Eugene Cernan, flew "Snoopy," the Apollo 10 lunar module, to within 47,000 feet (14 km) of the moon's surface.

On their return to Earth, Young, Stafford and Cernan set a record for the highest speed achieved by astronauts aboard a spacecraft: 24,791 mph (39,897 km/h) on May 26, 1969.

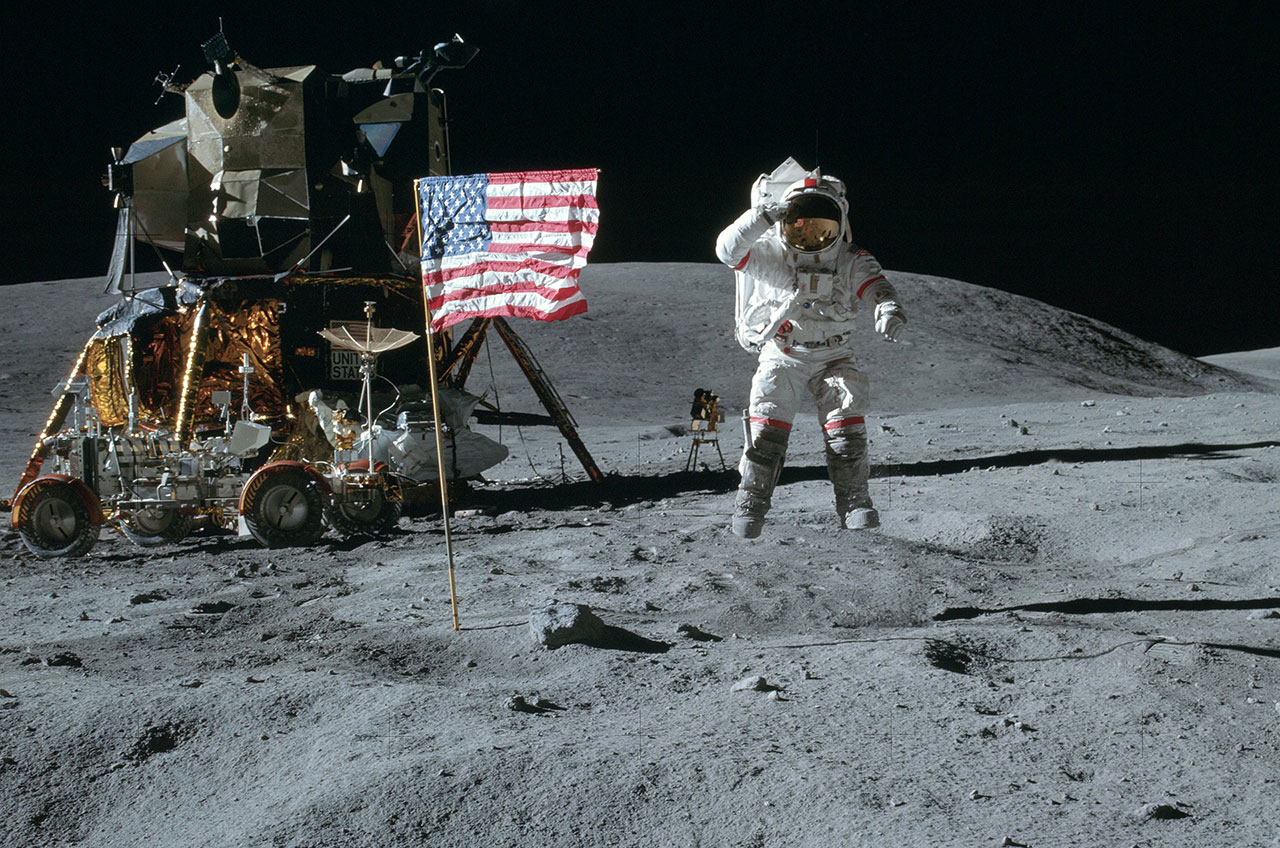

Young got his chance to walk on the moon in April 1972, as commander of Apollo 16, the fifth and penultimate Apollo lunar landing. Young and Charles Duke landed the "Orion" lunar module in the Descartes highlands for a nearly three-day stay.

"There you are, mysterious and unknown Descartes – Highland plains," described Young, as he took his first steps on the moon.

Exhibiting his dry wit, Young then compared his situation to a Joel Chandler Harris story, adapted for the Disney movie "Song of the South," to express how fortunate he felt to be on the moon.

"I'm sure glad they got ol' Br'er Rabbit here," he remarked, "back in the briar patch where he belongs."

Over the course of three excursions across the boulder-strewn surface, Young and Duke explored more than 16 miles (26 km), becoming the second crew to drive a lunar rover. As they went, they collected 211 pounds (96 kilograms) of moon rocks and lunar soil, which they brought back to Earth with Apollo 16 command module pilot Thomas "Ken" Mattingly.

During their first moonwalk, Young and Duke received word from Mission Control that the U.S. Congress had approved the funding to develop the space shuttle.

"The country needs that shuttle mighty bad," Young said in response. "You'll see."

Although he had no way of knowing it at the time, Young would next make history commanding the first flight of the space shuttle nine years later, almost to the day.

Young and Robert Crippen launched on space shuttle Columbia on April 12, 1981. Because of the way the orbiter had been designed, it could not be tested in space without a crew. [STS-1: The First Space Shuttle Flight in Pictures]

"I think if you look at all the things we had to do, flying a winged launch vehicle into space without any previous unmanned test, it probably was very bold," Young told collectSPACE.com in 2006, on the 25th anniversary of the STS-1 mission.

For two days and six hours, Young and Crippen tested Columbia's systems before returning to Earth like no other orbital spacecraft had done before — with wings, gliding to a touchdown on the dry lake bed at Edwards Air Force Base in southern California.

"This is the world's greatest flying machine, I'll tell you that," stated Young, as the orbiter came to a wheels stop under his control.

Young's then-record sixth space mission returned him to the commander's seat on board Columbia for the orbiter's sixth mission in November 1983. This time, Young led a crew of five, including the first international astronaut to fly on the shuttle, Ulf Merbold of the European Space Agency (ESA).

STS-9 also marked the the first flight of the European-built Spacelab laboratory, a pressurized module that was mounted inside the orbiter's payload bay. The 10-day mission carried out 72 experiments in astronomy, astrobiology, material sciences and Earth observation.

On Dec. 8, 1983, Columbia made a pre-dawn landing at Edwards, returning Young to Earth for the last time.

John Watts Young was born on Sept. 24, 1930, in San Francisco, California. When he was 18 months old, Young's parents moved, first to Georgia and then Orlando, Florida, where he attended elementary and high school.

Young earned his bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1952.

After graduation, he entered the U.S. Navy, serving on the destroyer USS Laws in the Korean War and then entering flight training before being assigned to a fighter squadron for four years.

Young graduated from the U.S. Navy Test Pilot School in 1959 and served at the Naval Air Test Center at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland, where he evaluated Crusader and Phantom fighter weapons systems. In 1962, he set world time-to-climb records to 3,000 and 25,000-meter (82,021 and 9,843-feet) altitudes in the F-4 Phantom.

Young retired from the U.S. Navy with the rank of captain in 1976. Over the course of his flying career, he logged more than 15,275 hours in props, jets, helicopters and rocket jets, including more than 9,200 hours in NASA's T-38 astronaut training jets.

In addition to his own six spaceflights, Young also served on five backup crews, including backup pilot for Gemini 6; backup command module pilot for the second Apollo mission (as slated before the Apollo 1 fire) and Apollo 7, the first crewed Apollo launch; and backup commander for Apollo 13 and Apollo 17.

In 1974, Young was named the fifth chief of the Astronaut Office, after serving for a year as the office's space shuttle branch chief. For 13 years, Young led NASA's astronaut corps, overseeing the crews assigned to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the approach and landing tests with the prototype orbiter Enterprise, and the first 25 space shuttle missions.

After the loss of space shuttle Challenger and its seven-person crew in January 1986, Young penned internal memos critical of NASA's attention to safety, a topic he had championed since his days flying Gemini. Young expressed concern over schedule pressure and wrote that other astronauts who had launched on missions preceding the ill-fated STS-51L mission were "very lucky" to be alive.

Young was subsequently reassigned to be special assistant to the director of the Johnson Space Center for engineering, operations and safety until 1996, when he was named the associate director for technical affairs, a position he held until his retirement from NASA on Dec. 31, 2004.

Young was the recipient of many honors for his contributions to space exploration, including the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, NASA Distinguished Service Medal, Rotary National Space Achievement Award, and six honorary doctorates. Young was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1988 and Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1993.

He was awarded the NASA Ambassador of Exploration in 2005, including a moon rock he assigned for display at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and was bestowed the General James E. Hill Lifetime Space Achievement Award from the Space Foundation in 2010. A stretch of Florida State Road 423 that runs through Orlando is named John Young Parkway in his honor.

Young is survived by his wife Susy, two children, Sandra and John, who he had with his first wife, Barbara White, and three grandchildren.

Follow collectSPACE.comon Facebookand on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2018 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.