TESS: NASA's Search for Earth-Like Planets

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is a NASA mission that's searching for planets orbiting the brightest stars in Earth's sky. Over its planned lifetime, the mission will monitor at least 200,000 stars for signs of exoplanets, ranging from Earth-size rocky worlds to huge gas giants. Scientists are hoping to find 10,000 alien worlds in the first two years of TESS operations. TESS was originally scheduled to last just two years, but in July 2019 NASA announced the mission would be extended until 2022. As of early 2019, TESS has confirmed a handful of planets and has hundreds of other possibilities to probe in its database.

Prime mission: Searching for close-by "Earths" heading here

TESS was first proposed in 2006 as a privately funded mission with financial backing from several institutions, including the Kavli Foundation, Google and donors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, according to NASA. It was eventually selected in 2013 as a mission in the Explorer program, which features large craft that do not exceed $200 million in launch costs.

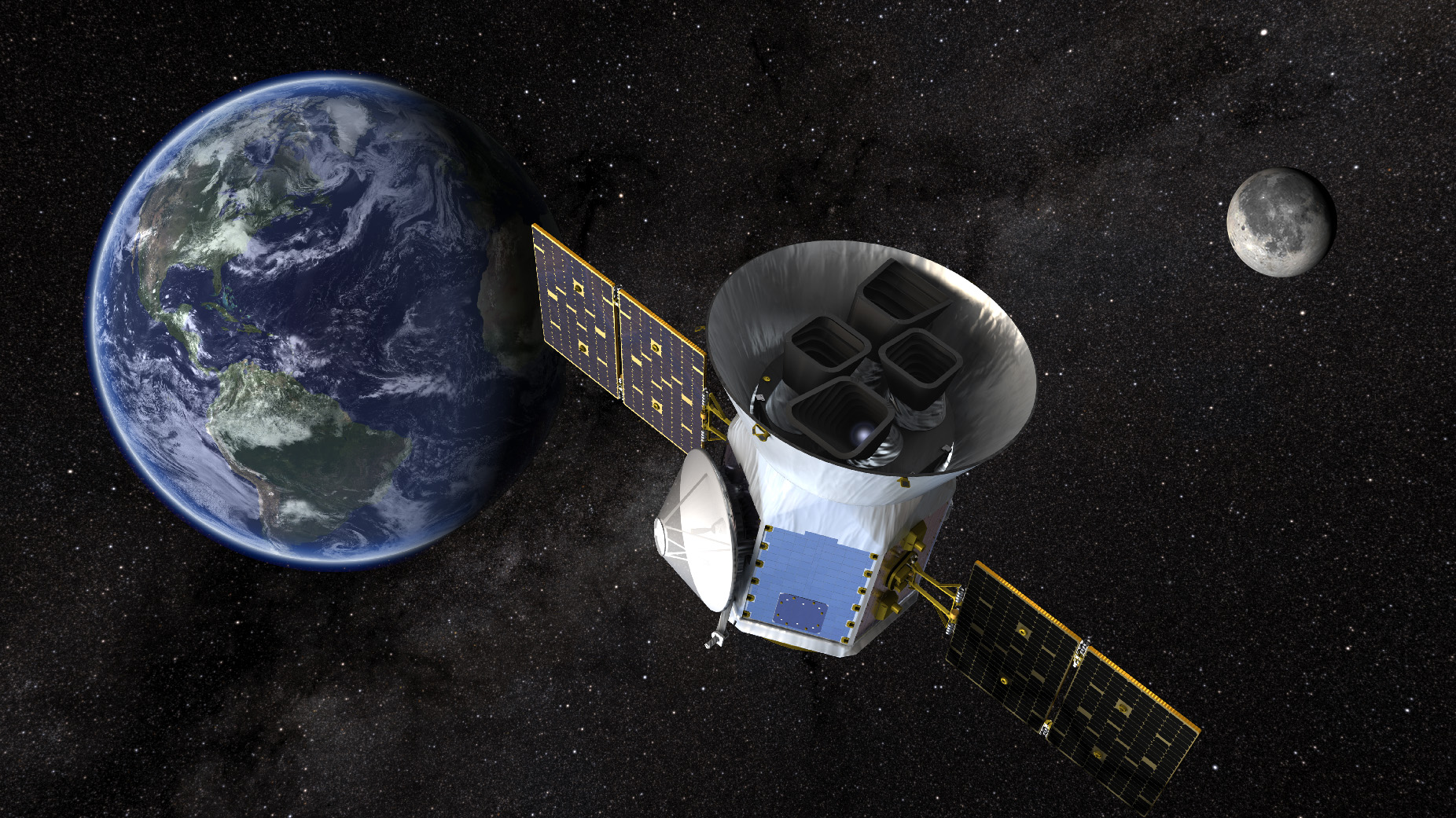

The mission launched on April 18, 2018, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida aboard a Falcon 9 rocket from SpaceX. From Earth, TESS made its way to a special orbit high above the planet, where it performs observations with minimal interference from Earth's atmosphere. Weeks after its launch, it made a close pass by the moon and sent back its first test image. After three months of commissioning, TESS began searching for planets in July. The mission's stated goal is to find at least 50 planets that are close to Earth's size (no more than four times Earth's diameter).

The first planet candidate find by TESS in September 2018 was a spectacular evaporating "super-Earth" that may be made of water, or it may have a rocky core and a hydrogen and helium atmosphere. Just days later, investigators found a candidate planet slightly larger than Earth that orbits a dim red dwarf star that's only 49 light-years away from our own planet — a relatively close neighbor.

Both of these finds came from examining TESS' first month of data, which was collected between July and August 2018. By early January 2019, TESS bagged its eighth confirmed planet (one that is a little smaller than Neptune) and its database of finds had hundreds of potential planetary candidates to investigate.

Astrophysicists involved with the TESS mission expect the planet hunter to find more than a thousand planets smaller than Neptune and dozens of Earth-size planets, according to a 2015 paper published in the Journal of Astronomical Telescopes, Instruments and Systems. The research team stated that public data releases will happen every four months.

Planet-hunting tools

TESS occupies a never-before-used orbit high above Earth, according to NASA. The elliptical orbit, called P/2, is exactly half the moon's orbital period, which means that TESS orbits Earth every 13.7 days. Its closest point to Earth (67,000 miles, or 108,000 kilometers) is about triple the distance of geosynchronous orbit, where most communications satellites operate. When TESS reaches this point in its orbit, it transmits data to ground stations in a process that takes about 3 hours. Then TESS passes through the Van Allen radiation belts to the highest point of its orbit, at 232,000 miles (373,000 km).

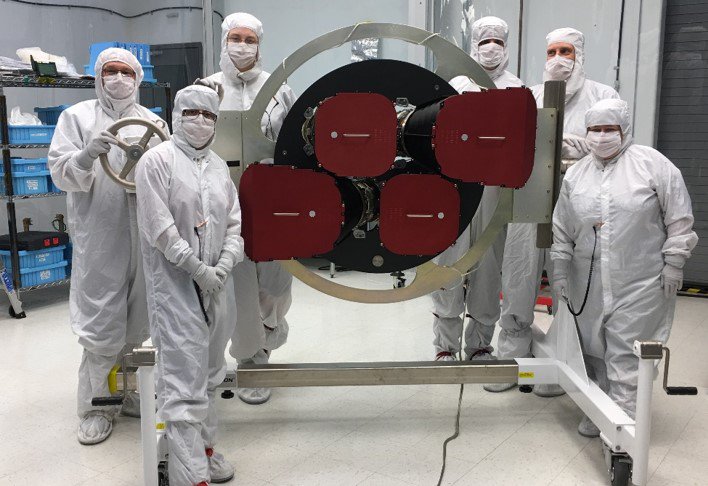

The solar-powered spacecraft carries four 100-millimeter-wide cameras that provide wide fields of view, according to NASA. The cameras stare at a particular region of the sky for between 27 and 351 days each, before moving on to another area. (The length of time will be decided according to where the region is in the sky, MIT said.) The spacecraft is expected to map the Southern Hemisphere in its first year, and the Northern Hemisphere in its second year.

The satellite is a follow-up of NASA's highly successful Kepler space telescope, which found thousands of exoplanets during a decade of work after its launch in 2009. (Kepler ran out of fuel in 2018, but its data archive continues to be analyzed and could yield more planets).

TESS, however, focuses on stars that are 30 to 100 times brighter than those Kepler examined, NASA said. It's much easier for ground telescopes to follow up on observations if the stars are bright, and easy to spot. The exoplanets TESS discovers will also be useful for the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, which can examine the planets for more information on their atmosphere and composition, after it launches no earlier than 2021.

Like Kepler, TESS examines variations in the brightness of stars. If an exoplanet passes in front of a star (called a planetary transit), it blocks a portion of the light and causes the brightness to dip. The mission is expected to collect thousands of candidate exoplanets, including Earth-sized and "super-Earth-size" planets. This will help astronomers better understand the structure of solar systems outside of our Earth, and provide insights into how our own solar system formed.

Additional resources:

- Stay up to date on NASA's latest news about TESS.

- The TESS website at MIT.

- Watch TESS catch a comet in this video from NASA.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.