Asteroid Bennu: The squishy space rock that almost swallowed a spacecraft

Bennu has a 1 in nearly 1,800 chance to hit Earth in the next 300 years.

- Why was Bennu chosen for the OSIRIS-REx sampling mission?

- Risky sample collection

- When was Bennu discovered?

- Bennu's size and orbit

- How did Bennu end up in our cosmic neighborhood?

- Bennu's strange surface

- Will Bennu hit Earth?

- What damage would Bennu cause if it were to hit Earth?

- Other asteroids visited by space probes

- Additional resources

- Bibliography:

Asteroid Bennu is a potentially hazardous near-Earth asteroid that was studied by NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission from 2018 to 2021.

The exploration, which involved a dramatic sample collection, made Bennu one of three best-explored asteroids in the entire universe. The OSIRIS-REx mission revealed multiple surprising facts about Bennu, including that its surface is so soft that it nearly swallowed up the probe during the sampling touchdown.

Despite the relatively high chances of Bennu's orbit intersecting with that of Earth in the next couple of centuries, most experts think the asteroid is rather harmless.

Related: 8 ways to stop an asteroid: Nuclear weapons, paint and Bruce Willis

Why was Bennu chosen for the OSIRIS-REx sampling mission?

Officially designated 101955 Bennu, the space rock was selected as a destination of NASA's first ever asteroid sample collection mission, the Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security-Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission, in 2008. Bennu stood out among 7,000 near-Earth asteroids known at that time, according to the University of Arizona, which manages the mission for NASA.

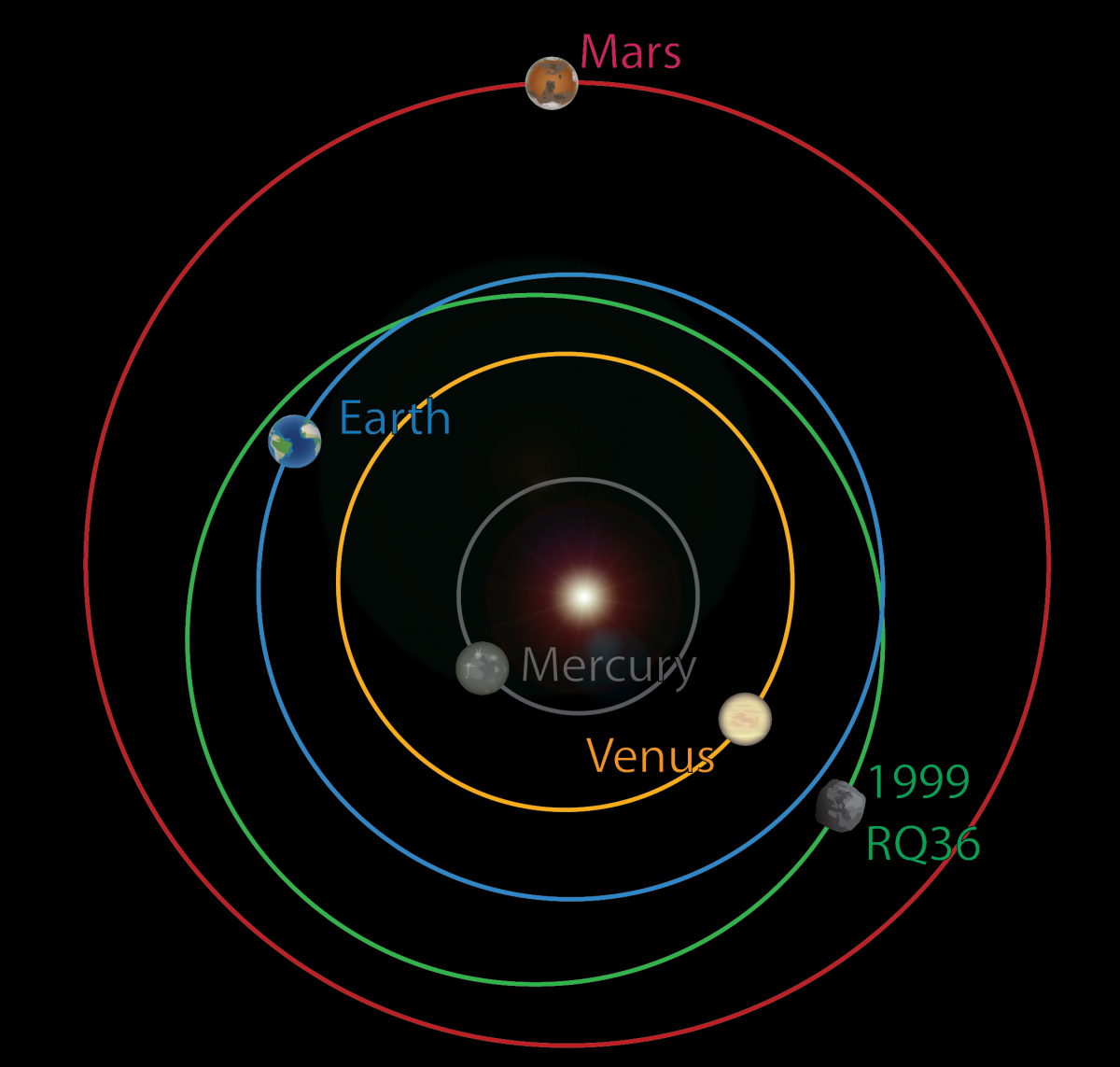

Near-Earth asteroids are space rocks that orbit the sun at distances similar to that of Earth. When designing the OSIRIS-REx mission, engineers were looking specifically for a rock traveling between 0.8 and 1.6 Astronomical Units (AU), or sun-Earth distances, from the sun. In addition to the right orbit, scientists also needed a rock that wouldn't spin too fast in order to allow for safe sample collection. That meant the asteroid needed to be wider than 656 feet (200 meters). Moreover, scientists were interested in visiting a special type of asteroid, a carbon-rich type that hasn't changed much since the early days of the solar system. Bennu was one of only five asteroids known at that time that ticked all the boxes.

Risky sample collection

The OSIRIS-REx mission set out for a two-year cruise to Bennu in September 2016 and entered into orbit around the spinning-top-shaped rock, in December 2018.

The spacecraft spent nearly two years remotely studying Bennu before making a successful, although rather dramatic, sample collection attempt in October 2020. During the sampling operation, OSIRIS-REx managed to collect 2 ounces (60 grams) of regolith from Bennu's surface, but the asteroid's response to the touchdown took the mission team by surprise. Bennu, a conglomeration of dirt, gravel and pebbles held together by only very weak gravitational forces nearly swallowed up OSIRIS-REx like a swamp, ejecting a wall of debris into space that threatened the spacecraft's safety.

OSIRIS-Rex left Bennu in May 2021 and is expected to drop off the precious sample at Earth in September 2023, before heading off for its extended mission to asteroid Apophis.

When was Bennu discovered?

Bennu was discovered in 1999 by the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR) telescope at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

Known under alternative designations as 1999 RQ36 or Asteroid 101955, Bennu received its name from a "Name That Asteroid" competition held by the University of Arizona in 2013.

Nine-year-old schoolboy Mike Puzio proposed the winning name, saying that the shape of the spacecraft designed to visit the asteroid, sporting an outstretched sample arm, looked like the heron god Bennu known from ancient Egyption mythology. The mythical bird is frequently associated with Osiris, the god of rebirth, fertility, but also death, which the scientists found symbolic of the double role of asteroids in the universe: sometimes they act as life destructors (such as in the case of the Chicxulub asteroid that caused the extinction of dinosaurs) but some of these rocks are also believed to have brought the building blocks of life to Earth billions of years ago.

Bennu's size and orbit

Bennu is 1,614 feet (492 m) wide and has a fairly regular shape that looks a bit like a spinning top.

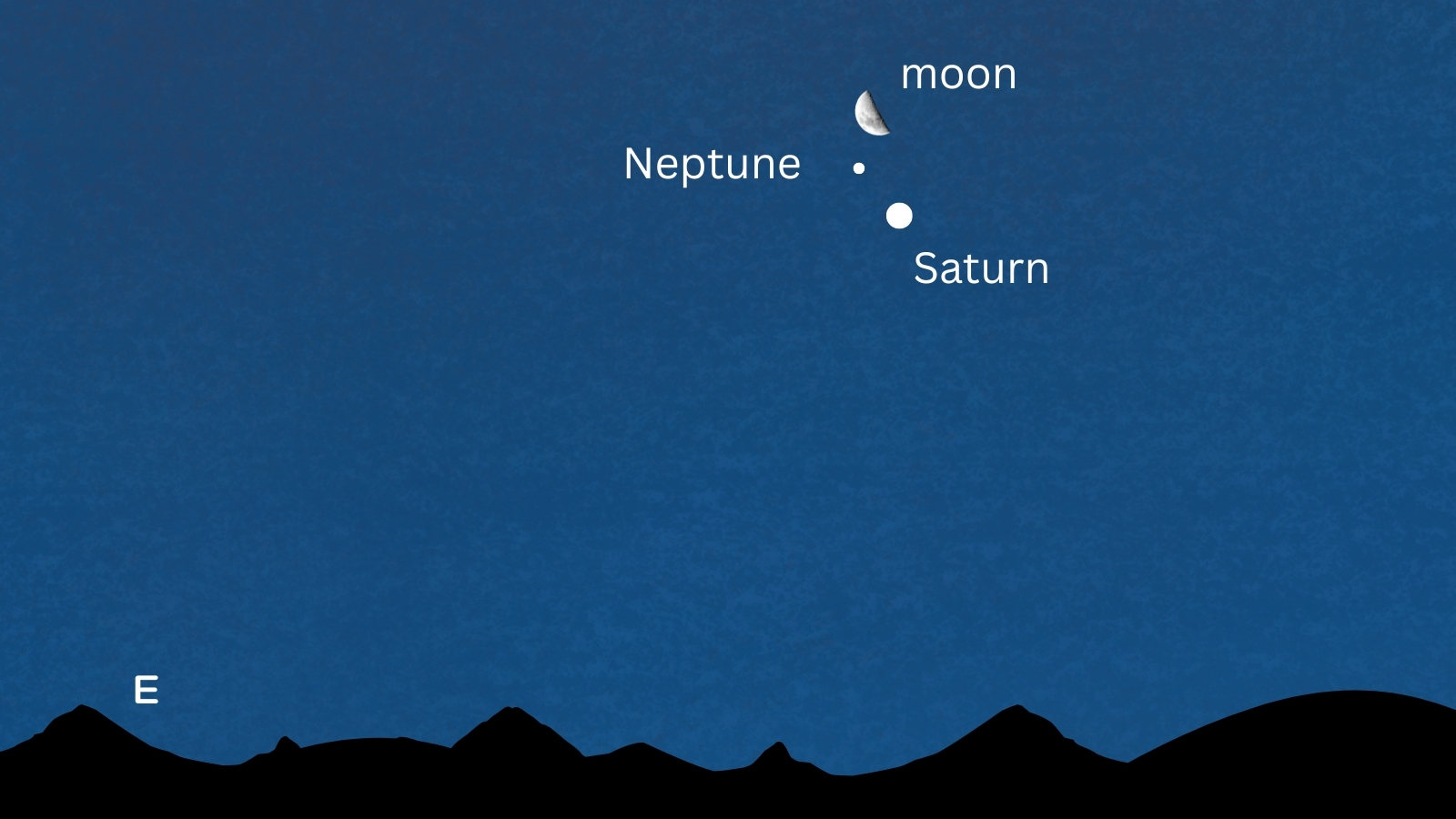

The asteroid completes one orbit around the sun every 435 Earth days and every six years makes a close approach to Earth, passing about 186,000 miles (300,000 km) from the planet's surface, which is closer than the orbit of the moon. One day on Bennu lasts 4.3 Earth hours, meaning the asteroid spins on its axis, completing one rotation in that period of time.

Related: Zoom! Asteroid Bennu Slips Past in OSIRIS-REx Flyby View

How did Bennu end up in our cosmic neighborhood?

A special kind of carbon-rich asteroid, Bennu is believed to contain organic compounds as old as the solar system itself, which, scientists hope, will help shed some light on the origins of life on our planet. Such asteroids usually live in the outer reaches of the asteroid belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, but sometimes migrate closer to the sun, which is exactly what happened to Bennu in the past.

The reason for Bennu's migration into Earth's neighborhood was the so-called Yarkovsky effect, a push generated by sunlight when the unusually dark carbon-rich asteroid absorbs its energy. Scientists think Bennu left the main asteroid belt after it broke off from a much larger body, up to 130 miles (200 km) wide, in a collision with another space rock. This collision may have happened between 700 million and 2 billion years ago. The parent body, as old as the solar system itself, was until then rather unchanged, featuring chemistry and mineralogy typical for the earliest stages of the solar system's evolution. Bennu inherited this unique time-capsule quality and brought it within scientists' reach.

Bennu's strange surface

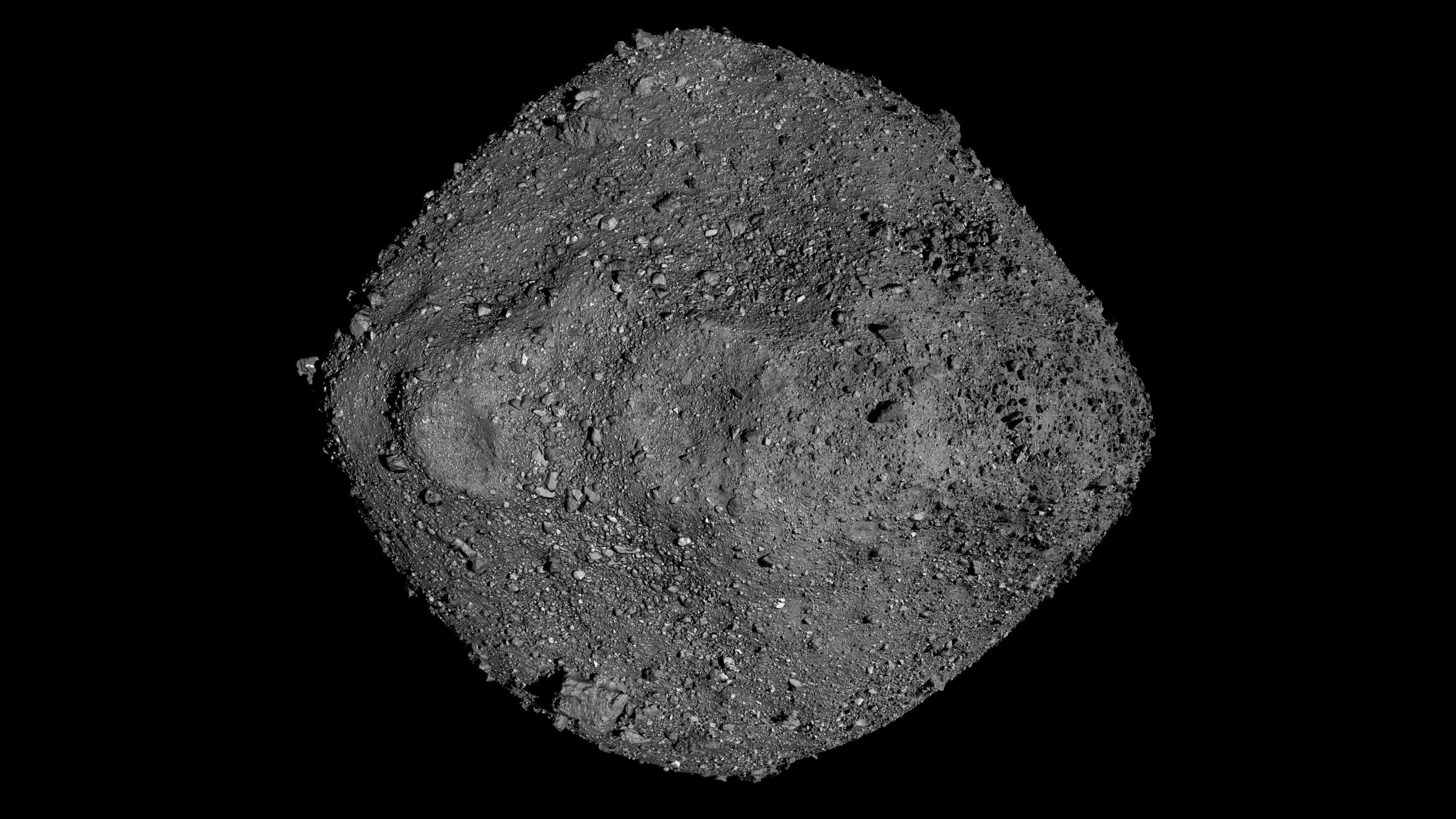

Having been born in a collision, Bennu is not a single piece of rock. Instead, it is what scientists call a rubble pile, a loose conglomeration of dirt, rocks and pebbles held together only by the body's weak gravitational forces.

When OSIRIS-REx first arrived at Bennu, it quickly revealed that the asteroid's surface looked quite different from what scientists had expected. Instead of being a neat ball of small pebbles and gravel, Bennu's surface was peppered with large boulders that made selecting a safe landing site difficult.

When OSIRIS-REx finally made its sample-collecting touch-down in October 2020 in a carefully selected site called Nightingale Crater, the surface gave nearly no resistance, and the probe only escaped from being swallowed up by the squishy sphere thanks to its powerful thrusters. The asteroid's response was a complete surprise to the scientists, showing that Bennu behaves almost like a sphere of liquid rather than a clump of solid material.

This liquid-like quality is likely responsible for the fact that OSIRIS-REx found much fewer craters on Bennu than scientists expected based on the statistical frequency of meteorite impacts. Since asteroids like Bennu are devoid of weather-producing atmospheres and geological processes such as volcanism and erosion, scientists expected to find a long track record of past encounters with other space rocks dating back hundreds of millions of years. The observations, however, suggested that Bennu's soft surface acts almost like a crumple zone of a car, absorbing a large portion of the impacts nearly without a trace.

While the asteroid is believed to be a time capsule of ancient solar system geology, its surface, on the contrary, appears to be constantly changing, with traces of past impacts wiped out every few million years.

Traces of impacts may not last long (in cosmic terms), these impacts can, however, initially create massive scars. The touch-down of OSIRIS-Rex, for example, produced a 26-foot-wide (8 m) hole inside Nightingale Crater.

OSIRIS-REx's observations also revealed that Bennu's surface is full of strange cracks, which, scientists think, are caused by the intense sunlight that Bennu is exposed to. These cracks appear quite young, only tens of thousands of years old, suggesting that asteroids such as Bennu age much faster than planets protected by atmospheres such as our Earth.

Will Bennu hit Earth?

While Bennu is officially one of the most likely bodies to collide with Earth in the next thousand years, the odds of this collision actually happening are still extremely low. A NASA study from August 2021 concluded that the probability of the two bodies meeting in space through 2300 is about 1 in 1,750. The study took into account OSIRIS-REx measurements of Bennu, which means it included the most accurate data on all sorts of parameters that could affect Bennu's trajectory, including the specifics of its shape and orbital motions during OSIRIS-REx's time in the asteroid's orbit.

What damage would Bennu cause if it were to hit Earth?

At 1,614 feet (492 m) wide, Bennu would certainly cause quite some destruction if it were to hit our planet. This rock's impact wouldn't trigger a mass extinction event, but the reverberations would be felt across several U.S. states (if the rock were to land in the United States). The crater after Bennu's impact would be nearly 4 miles wide (6.4 km) with the airblast knocking down buildings tens of miles away from the epicenter and shattering windows hundreds of miles away, according to this impact calculator tool by Imperial College London.

The good news is that if Bennu were to stray too close to our planet, NASA may have a tool to prevent the collision thanks to the recent Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, which successfully changed the orbit of an asteroid moonlet Dimorphos around a parent space rock Didymos on September 2022.

Other asteroids visited by space probes

Only three other asteroids were studied in detail by visiting spacecraft. The first probe ever to collect a sample from an asteroid was Japan's Hayabusa 1, which visited a space rock called Itokawa in 2005. The mission's success prompted a follow-up, the Hayabusa 2 mission, which studied asteroid Ryugu in 2018 and 2019. Both Hayabusas successfully delivered asteroid samples back home. Even before the Hayabusa missions, NASA's NEAR Shoemaker probe orbited and extensively photographed the surface of asteroid EROS in 2000. That probe ended its life by landing on EROS' surface in 2001.

Additional resources

There are plenty of resources about this fascinating space rock on the internet. You can start by exploring the mission's page run jointly by NASA, the University of Arizona and Lockheed Martin.

Here is a short video about what would happen if Bennu were to hit Earth and NASA's video tour of the asteroid composed of OSIRIS-REx images.

Bibliography:

NASA, Bennu — Overview https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/asteroids-comets-and-meteors/asteroids/101955-bennu/overview/

NASA, Ten things to know about Bennu, October, 2020 https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2020/bennu-top-ten

Asteroidmission.org, Why Bennu https://www.asteroidmission.org/why-bennu/

Canadian Space Agency, Destination Bennu https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/satellites/osiris-rex/destination-bennu.asp

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.