Mars InSight Stuck the Landing. Here's the First Thing It Did.

Mars has a new robotic inhabitant on its surface. At 2:54 p.m. ET Nov. 26, NASA mission control confirmed that the InSight lander had safely reached the surface of the Red Planet, following a harrowing descent that had engineers tensely perched on the edges of their seats.

InSight reached Mars' atmosphere traveling at 12,300 mph (19,795 km/h). During the minutes that followed, the rapidly dropping lander deployed a parachute, ejected its heat shield and fired 12 descent engines to slow the last part of its fall, finally touching down on Mars.

After this remarkable landing, InSight immediately got to work. Within 10 seconds after touchdown, InSight's instruments were already engaged in the mission's first tasks — establishing a direct-to-Earth signal and taking photos of the landing site, Jim Green, NASA Chief Scientist, told Live Science. [NASA's InSight Mars Lander: Full Coverage]

By 3:03 p.m. ET, NASA reported the first "beep" from InSight, confirming that the lander was OK. According to the readings, InSight was "in normal mode" and "is not complaining," NASA systems engineer Rob Manning said during a live stream of the event.

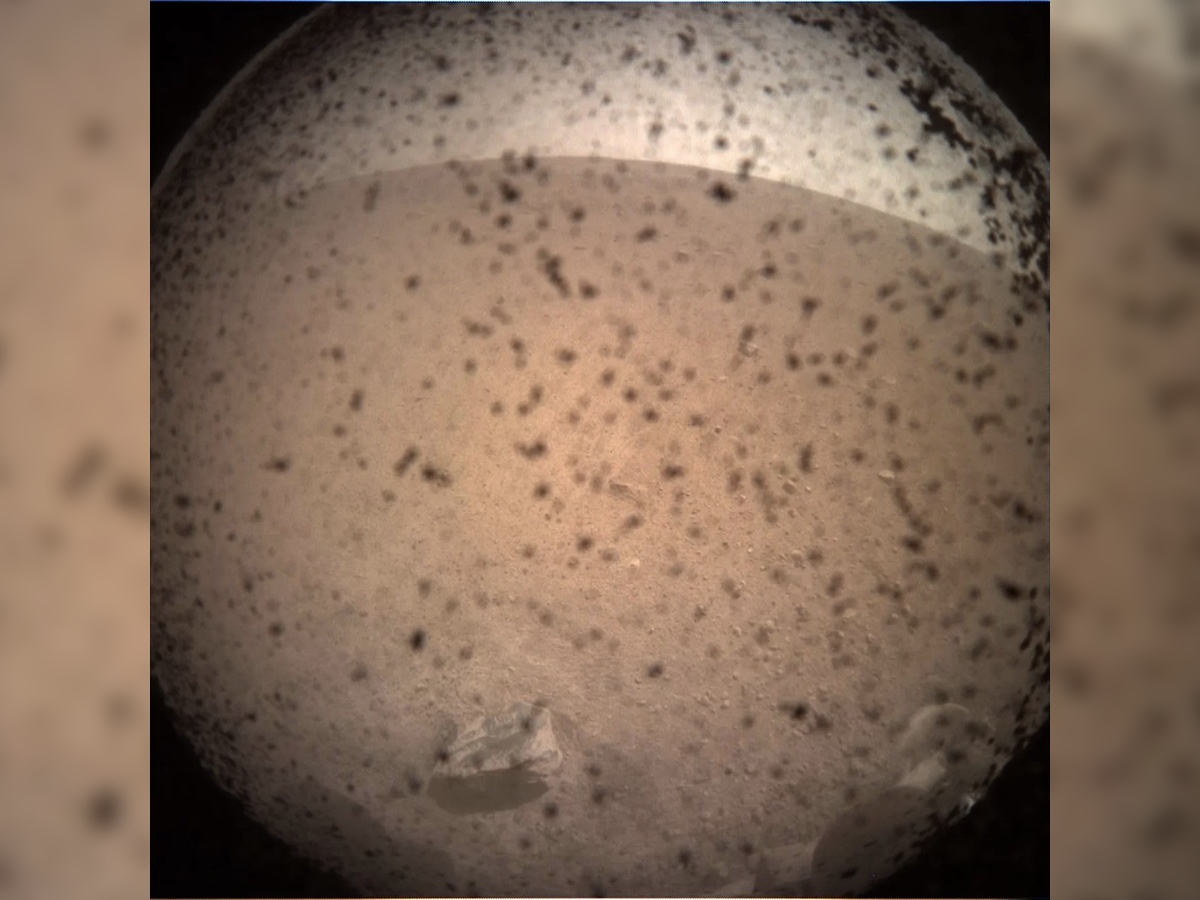

And minutes after the landing, NASA already had its first glimpse of Mars through one of InSight's "eyes," as the wide-angle camera captured a reddish patch of ground in front of the lander; the terrain appeared to be rock-free. Black spots on the image were dust grains sticking to the lens's cover, NASA representatives explained during the live stream.

One of InSight's first tasks on Mars was to set up its power source; its first minutes on Mars were powered entirely by battery, as the solar panels attached to the carrier spacecraft were ditched prior to InSight's descent, Green said.

InSight's battery can power the lander for up to 16 hours on a single charge, but, even so, InSight needed to get its own solar array up and running — or its life on Mars would be very, very short, Green said. About 16 minutes after the landing, enough time will have passed for the dust to settle. Then, the solar panels were expected to deploy without additional instruction from Earth, Green explained.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"When I see the battery voltage back up and the engineering data at 100 percent, then I will know we have a mission," he said.

After the solar panels are activated, InSight will take more photos and begin setting up the rest of the instruments. The lander carries two cameras: a wide-angle camera positioned underneath its body points in the direction where InSight will place its instruments, and another camera mounted on InSight's arm, which NASA engineers will use to examine what's happening on the lander, Green explained.

Once they've confirmed that the lander is in good shape, they can begin to deploy the seismometer (SEIS), which will measure "marsquakes." As soon as the SEIS instrument is in place, InSight will set up the HP3 heat probe, which will take Mars' temperature.

"It's like a cake," Green said. "You bake a cake, and when you take it from the oven, it's still hot inside while it's cooling off. All the planets are still cooling off from when they were made 4.5 billion years ago. And so, the interior of Mars is hot, and that heat is still filtering through the mantle and the crust — and HP3 is designed to make that measurement."

Updates from InSight will be beamed via an ultra high-frequency radio signal (UHF) to orbiting satellites, which will store the data onboard and relay them to Earth.

However, there are still many weeks of setup work ahead for InSight — a process that will be "slow and methodical" — and it will likely be at least a few months into 2019 before the mission's real Mars science begins, he added.

"By March, I would say, we'll be in the mode of this platform doing its job — listening for quakes and also measuring the heat leaving the planet," Green said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.