A Sleepy Science: Will Humans Hibernate Their Way Through Space?

In the future, bedtime for astronauts may be more than a few evening hours of regular shuteye. It may help them reach other planets, though admittedly they would have to sleep for quite a long time.

European researchers, however, are on the case, conducting hibernation experiments that will hopefully help them understand whether humans could ever sleep through the multiple years it would take for a spaceflight to the outer planets or beyond.

"At the moment, the level of inquiry really is just speculative," said Mark Ayre, of the European Space Agency (ESA), in an e-mail interview. "[Our] interest in this topic is borne out of the realization that, if it were an effective technology, it could be an enabler for deep-space manned missions."

What seems like science fiction is not completely far-fetched. Researchers have been able to chemically induce a stasis-like state in living cells and have moved on to small, non-hibernating mammals like rats.

"We're providing some state-of-the-art, basic research on the field of hibernation," said Marco Biggiogera, a hibernation researcher at Italy's University of Pavia, adding that he and two colleagues, each from different Italian universities, are studying hibernation mechanisms for ESA.

Ayre, a researcher with ESA's Advanced Concepts Team in Noordwijk, The Netherlands, said a theoretical human hibernation system could one day save massive amounts of space on long-duration human spaceflights.

"A major mass-saver for this would be a reduction in the pressurized volume required psychologically by the astronauts," Ayre said, adding that a sleeping crew could also drastically reduce the amount of consumable supplies required for a multi-year journey.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The science of sleep

Hibernating animals such as bears or woodchucks can either go into a full hibernate, in which they effectively sleep through a long stretch of time, or go into a torpor, a sort of periodic sleep from which they awake several times during winter.

"All of them belong to a hypermetabolic stasis, where you lower your metabolism, your energy consumption and your energy needs," Biggiogera told SPACE.com. "It's an adaptive mechanism."

The key seems to be genetic, where special genes allow animals to sleep for long periods, while protecting them from harsh temperatures or a lack of food, Biggiogera said.

Biggiogera and his colleagues were able to create a hibernation-like state in cell cultures using a substance called DADLE, which has opium-like properties and is similar to a family of molecules produced in the human brain.

In cells, DADLE reduced proliferation and the transcription of genetic material, effectively putting the cells to sleep.

"The most interesting thing is that you can reverse everything by taking the molecule away," Biggiogera said. "At least in cell cultures, you reduce the risk of side effects."

Short missions need not apply

Medical research, however, is just half of a potential spaceflight hibernation system. There is also the engineering side as well.

"There would be a problem in that the crew would not be able to respond to contingency events, such as fires and so forth," Ayre said, of a hibernating crew. "This would require that the degree of automation on board the ship was sufficient to deal with these risks."

Then there is the challenge of designing a suitable hibernaculum, the protective shelter or nest animals build to sleep in, for humans.

As envisioned by ESA researchers, such a shelter would provide the proper environment for hibernation - such as the proper temperature - and also serve as a bed in the waking part of the mission. It would also have to protect crewmembers from solar flares, monitor life functions and serve the physiological needs of the hibernator, Ayre said.

While a sleeping crew consumes less fuel, water and other cargo and would require less room to move about, a hibernation system is still a substantial amount of hardware.

"The associated mass and volume penalties are still likely to be considerable for a long-duration missions," Ayre said.

With those challenges in mind, ESA researchers said a manned spaceflight would have to be a lofty endeavor to warrant the use of crew hibernation. Even the two-year trip to Mars would not be long enough such an effort, they said.

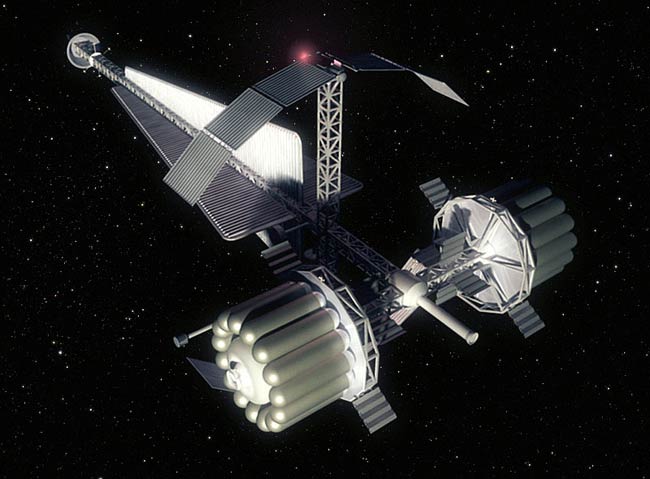

However, a far-flung manned mission to the outer planets, such as the six-person Human Outer Planets Exploration (HOPE) mission to the Jovian moon Callisto studied by NASA, could be a potential candidate, Ayre said.

A 2002 conceptual study by NASA's Revolutionary Aerospace Systems Concepts (RASC) group, the HOPE Callisto mission proposes sending six humans on a 5-year flight to Callisto, where they would spend 30 days on the Jupiter moon's surface, by the year 2045 or later.

NASA spokeswoman Dolores Beasley said the space agency's Office of Biological and Physical Research's Bioastronautics Research Division is not currently pursuing hibernation research for future human space missions.

Rats first, humans MUCH later

With the cell culture study behind them, Biggiogera and his colleagues are now studying the effects of DADLE in laboratory rats, with results anticipated by the end of 2004.

But the research still has a long way to go.

A major challenge, Biggiogera said, is the fact that cell cultures can be very simplified systems, whereas the organs -- then the organs working together as a living body -- are complex.

"It's like moving from a simple Apple computer to a supercomputer," Biggiogera said. "We are not on the way to make humans hibernate. We are still very, very far from that."

But despite the challenge still ahead, Biggiogera can see the potential benefits of an effective human hibernation system.

Injecting human hearts or lungs with a hibernation-inducing agent could preserve them for transplants much longer than current methods, he said, adding that a severely wounded person, soldier or police officer could be put into a hibernation state until hospital treatment was available.

"Obviously for science fiction or for ESA, you want to think of space exploration," he said. "But this can be of help in many cases."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.