The seven stars from which we derive the Little Bear, or Ursa Minor in the night sky are also known as the Little Dipper.

Polaris, the North Star lies at the end of the handle of the Little Dipper, whose stars are rather faint. Its four faintest stars can be blotted out with very little moonlight or street lighting.

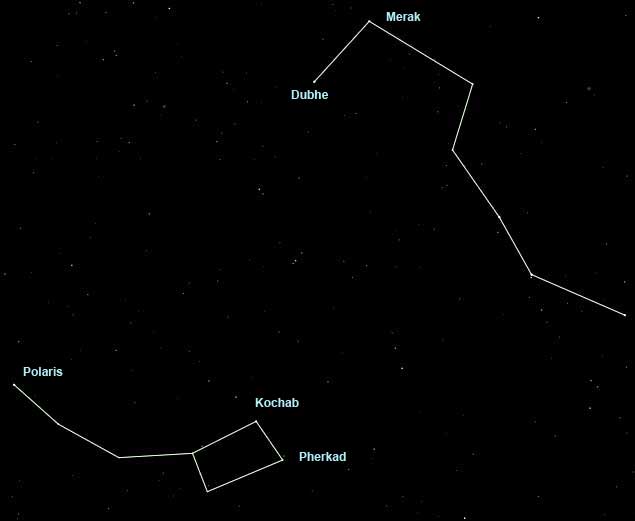

The best way to find your way to Polaris is to use the so-called pointer stars in the bowl of the Big Dipper, Dubhe and Merak. Just draw a line, between these two stars and prolong it about 5 times, and you eventually will arrive in the vicinity of Polaris.

Exactly where you see Polaris in your northern sky depends on your latitude. From New York City it's almost halfway from the horizon to the overhead point (called the zenith). At the North Pole, you would find it directly overhead. At the equator, Polaris would appear to sit right on the horizon. So if you travel to the north, the North Star climbs progressively higher the farther north you go. When you head south, the star drops lower and ultimately disappears once you cross the equator and head into the Southern Hemisphere.

What to look for

Aside from the North Star the two stars at the front of the Little Dipper's bowl are the only ones readily seen. These two are often referred to as the "Guardians of the Pole" because they appear to march around Polaris like sentries; the nearest of the bright stars to the celestial pole except for Polaris itself. Columbus mentioned these stars in the log of his famous journey across the ocean and many other navigators have found them useful in measuring the hour of the night and their place upon the sea.

The brightest Guardian is Kochab, a second magnitude star with an orange hue. The other Guardian goes by an old Arabian name, Pherkad – the "Dim One of the Two Calves." Pherkad is indeed dimmer than Kochab, shining at third magnitude.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The two other stars that complete the pattern of the bowl of the Little Dipper are of fourth and fifth magnitude, which means you may struggle to see them from a city or suburban setting.

Thus, the bowl of the Little Dipper, which is visible at any hour on any night of the year from most localities in the Northern Hemisphere, can serve as an indicator for rating just how dark and clear your night sky really is. If, for example, you can readily see all four stars in the bowl, you've got yourself a good-to-excellent sky. Unfortunately, thanks to the spread of light pollution in recent years, only the Guardians are usually visible from most city and suburban sites, meaning the quality of the sky would rank fair-to-poor.

Interestingly, the Big and Little Dippers are arranged so that when one is upright, the other is upside down. In addition, their handles appear to extend in opposite directions. Of course, the Big Dipper is by far the brighter of the two, appearing as a long-handled pan, while the Little Dipper resembles a dim ladle.

North Star myth

Finally, there is a popular misconception in that many believe that the North Star is the brightest star in the sky.

I still remember when I was a very young boy how an uncle of mine pointed to a brilliant bluish star high in the midsummer sky and told me that it was the North Star (it was actually Vega, in the constellation Lyra). Yet Polaris actually ranks only 49th in brightness. It remains in very nearly the same spot in the sky year-round while the other stars circle around it. Only the apparent width of about one and a half full Moons separates Polaris from the pivot point directly in the north around which the stars go daily.

However, on account of the wobble of the Earth's axis (called precession), the celestial pole shifts as the centuries go by.

Polaris is actually still drawing closer to the pole and on March 24, 2100, it will be as close to it as it ever will come, just 27.15 arc-minutes or slightly less than the Moon's apparent diameter. Since it takes just under 26,000-years for the Earth's axis to complete a single wobble, different stars have become the North Star at different times. In fact, the brightest Guardian, Kochab, was the North Star at the time of Plato, around 400 BC.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.