Fluffy Mystery at Edge of Solar System Solved

Our solar system is passing through a cloud of interstellar material that shouldn't be there, astronomers say. And now the decades-old Voyager spacecraft have helped solved the mystery.

The cloud is called the "Local Fluff." It's about 30 light-years wide and holds a wispy mix of hydrogen and helium atoms, according to a NASA statement released today. Stars that exploded nearby, about 10 million years ago, should have crushed the Fluff or blown it away.

So what's holding the Fluff in place?

"Using data from Voyager, we have discovered a strong magnetic field just outside the solar system," explained Merav Opher, a NASA Heliophysics Guest Investigator from George Mason University. "This magnetic field holds the interstellar cloud together ["The Fluff"] and solves the long-standing puzzle of how it can exist at all."

The Fluff is much more strongly magnetized than anyone had previously suspected," Opher said. "This magnetic field can provide the extra pressure required to resist destruction."

Opher and colleagues detail the discovery in the Dec. 24 issue of the journal Nature.

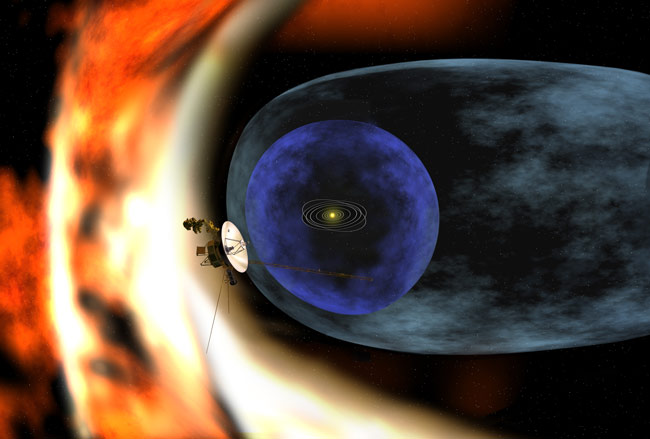

NASA's two Voyager probes have been racing out of the solar system for more than 30 years. They are now beyond the orbit of Pluto and on the verge of entering interstellar space. During the 1990s, Voyager 1 became the farthest manmade object in space.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Voyager craft, racing in opposite directions, have revealed among other things that the bubble around our solar system is squashed.

"The Voyagers are not actually inside the Local Fluff," Opher said. "But they are getting close and can sense what the cloud is like as they approach it."

The Fluff is held at bay just beyond the edge of the solar system by the sun's magnetic field, which is inflated by solar wind into a magnetic bubble more than 6.2 billion miles wide (10 billion km). Called the "heliosphere," this bubble protect the inner solar system from galactic cosmic rays and interstellar clouds. The two Voyagers are located in the outermost layer of the heliosphere, or "heliosheath," where the solar wind is slowed by the pressure of interstellar gas.

Voyager 1 entered the heliosheath in December 2004. Voyager 2 followed in August 2007. These crossings provided key data for the new study.

Other interstellar clouds might also be magnetized, Opher and colleagues figure. And we could eventually run into some of them.

"Their strong magnetic fields could compress the heliosphere even more than it is compressed now," according to NASA. "Additional compression could allow more cosmic rays to reach the inner solar system, possibly affecting terrestrial climate and the ability of astronauts to travel safely through space."

- Top 10 Voyager Facts

- Gallery: Voyager's Photo Legacy

- The Strangest Things in Space

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Space.com is the premier source of space exploration, innovation and astronomy news, chronicling (and celebrating) humanity's ongoing expansion across the final frontier. Originally founded in 1999, Space.com is, and always has been, the passion of writers and editors who are space fans and also trained journalists. Our current news team consists of Editor-in-Chief Tariq Malik; Editor Hanneke Weitering, Senior Space Writer Mike Wall; Senior Writer Meghan Bartels; Senior Writer Chelsea Gohd, Senior Writer Tereza Pultarova and Staff Writer Alexander Cox, focusing on e-commerce. Senior Producer Steve Spaleta oversees our space videos, with Diana Whitcroft as our Social Media Editor.