'Doomsday Glacier' is teetering even closer to disaster than scientists thought, new seafloor map shows

Researchers say the icy mass is "holding on by its fingernails."

Underwater robots that peered under Antarctica's Thwaites Glacier, nicknamed the "Doomsday Glacier," saw that its doom may come sooner than expected with an extreme spike in ice loss. A detailed map of the seafloor surrounding the icy behemoth has revealed that the glacier underwent periods of rapid retreat within the last few centuries, which could be triggered again through melt driven by climate change.

Thwaites Glacier is a massive chunk of ice — around the same size as the state of Florida in the U.S. or the entirety of the United Kingdom — that is slowly melting into the ocean off West Antarctica. The glacier gets its ominous nickname because of the "spine-chilling" implications of its total liquidation, which could raise global sea levels between 3 and 10 feet (0.9 and 3 meters), researchers said in a statement. Due to climate change, the enormous frozen mass is retreating twice as fast as it was 30 years ago and is losing around 50 billion tons (45 billion metric tons) of ice annually, according to the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration.

The Thwaites Glacier extends well below the ocean's surface and is held in place by jagged points on the seafloor that slow the glacier's slide into the water. Sections of seafloor that grab hold of a glacier's underbelly are known as "grounding points," and play a key role in how quickly a glacier can retreat.

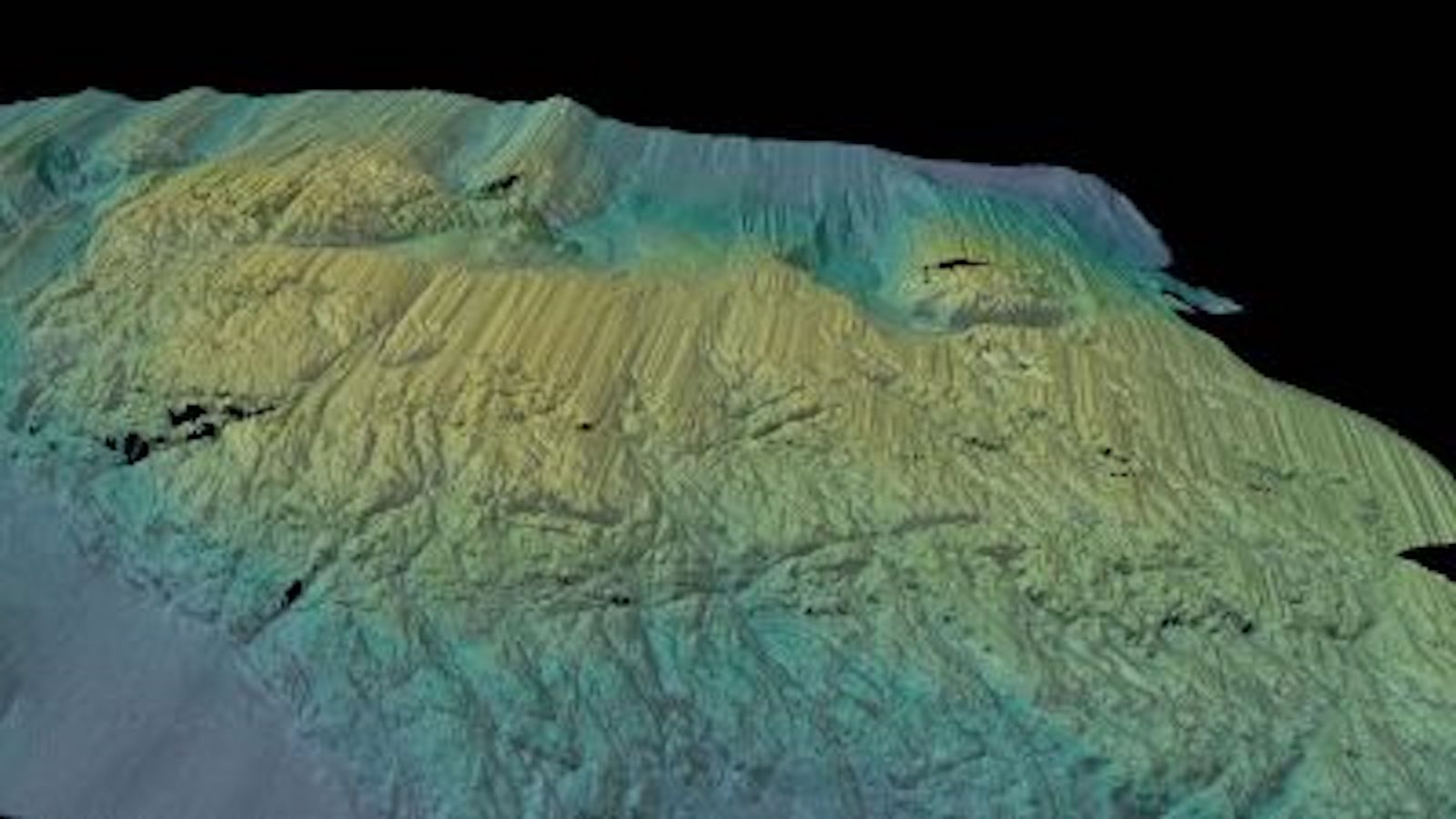

In the new study, an international team of researchers used an underwater robot to map out one of Thwaites' past grounding points: a protruding seafloor ridge known as "the bump," which is around 2,133 feet (650 m) below the surface. The resulting map revealed that at some point during the last two centuries, when the bump was propping up Thwaites Glacier, the glacier's ice mass retreated more than twice as fast as it does now.

Related: Antarctica's 'Doomsday Glacier' could meet its doom within 3 years

Researchers say the new map is like a "crystal ball" showing us what could happen to the glacier in the future if it becomes detached from its current grounding point — which is around 984 feet (300 m) below the surface — and gets anchored to a deeper one like the bump. This scenario could become more likely in the future if increasingly warmer waters melt away the glacier's guts, according to the statement.

"Thwaites is really holding on today by its fingernails," study co-author Robert Larter, a marine geophysicist with the British Antarctic Survey, said in the statement. "We should expect to see big changes over small timescales in the future."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Reading between the lines

Researchers mapped out the bump using the underwater robot Rán (named after the Norse goddess of the sea), which spent around 20 hours scanning a 5-square-mile (13 square kilometers) section of the former grounding point.

The resulting map showed that the bump is covered with around 160 parallel grooved lines that give it a barcode-like appearance. These strange-looking grooves, which are also known as ribs, are between 0.3 and 2.3 feet (0.1 and 0.7 m) deep. The spaces between the ribs range short and wide, between 5.2 and 34.4 feet (1.6 and 10.5 m) apart, but they are most commonly around 23 feet (7 m) apart.

These ribs are actually imprints that were left behind as the high tide briefly lifted the glacier off the seafloor, which slightly nudged the ice mass further inland before the low tide lowered it back down. Each rib represents a single day; collectively, the lines map out the gradual movement of the glacier over a period of around 5.5 months. The varying depths and spaces between the ribs match the cycle of spring and neap tides, with the glacier being moved farther and with greater force during the former. (During spring tides, high tides are higher and low tides are lower. During neap tides, high tides are lower and low tides are higher.)

"It's as if you are looking at a tide gauge on the seafloor," study lead researcher Alastair Graham, a geological oceanographer at the University of South Florida, said in the statement. "It really blows my mind how beautiful the data are." However, the eye-catching grooves on the seafloor are also cause for concern, he added.

Based on the spacing of the ribs, the researchers estimated that when the Thwaites glacier was anchored on the bump, the icy mass retreated at a rate of between 1.3 and 1.4 miles (2.1 and 2.3 km) per year. This means that the glacier was retreating almost three times faster than it was between 2011 and 2019, when it was receding at a rate of around 0.5 miles (0.8 km) per year, according to satellite data.

Related: Alarming heat waves hit Arctic and Antarctica at the same time

Researchers are unsure exactly when the glacier sat on top of the bump, but it was definitely within the last two centuries and was most probably sometime before the 1950s. The team was unable to take the necessary core samples from the seafloor to properly age the bump because increasingly icy conditions around the glacier meant that they, too, had to swiftly retreat from the region, according to the statement. However, the team intends to return soon to properly answer this important question.

The new findings are worrying because they show that the Thwaites glacier experienced "pulses of very rapid retreat" even before the effects of climate change increased the current rate of ice loss, Graham said. It shows that the glacier has the potential to accelerate much faster if it becomes detached from its current grounding point and anchors to a subsequent bump-like grounding point, he added.

Past research using robotic subs has shown that surprisingly warm water beneath the glacier may be melting the underbelly of the icy mass, which could quickly push the glacier toward this tipping point.

"Once the glacier retreats beyond [the current] shallow ridge in its bed," it could take just a few years to accelerate to a similar rate of retreat during the age of the bump, Larter said.

The study was published online Monday (Sept. 5) in the journal Nature Geoscience.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Harry is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. He studied Marine Biology at the University of Exeter (Penryn campus) and after graduating started his own blog site "Marine Madness," which he continues to run with other ocean enthusiasts. He is also interested in evolution, climate change, robots, space exploration, environmental conservation and anything that's been fossilized. When not at work he can be found watching sci-fi films, playing old Pokemon games or running (probably slower than he'd like).