Here's how NASA's Artemis 1 Orion spacecraft will splash down to end its moon mission in 8 not-so-easy steps

A skip, a re-entry and a series of parachute deployments will send Orion into the Pacific Ocean on Sunday (Dec. 11.)

In its last few minutes in space, the Orion spacecraft has a big job to do.

The Artemis 1 mission launched the NASA Orion capsule safely into deep space on Nov. 16, and after a nearly month that saw it fly around the moon, it's time for the vehicle to come home.

Returning on Sunday (Dec. 11) won't be easy. Orion will do an unprecedented "skip" off the atmosphere of Earth before returning to our planet in earnest. Then it must deploy a series of parachutes to make a safe ocean splashdown within reach of U.S. Navy recovery ships.

Artemis 1's final moments need to go exceedingly well for NASA to approve future missions of the Artemis program, which are slated to continue with Artemis 2 bringing astronauts around the moon in 2024 and Artemis 3 landing upon the surface in 2025 or so.

The eight main steps of Orion's epic landing sequence are below.

1. Orion capsule separates from service module

The first major event in Orion's return to Earth is the crew capsule's separation from its service module, which was built by the European Space Agency and contains the thrusters, engine and solar arrays for the spacecraft.

The Orion capsule will separate from its service module at about 12 p.m. EST (1700 GMT), about 40 minutes before splashdown, NASA has said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

2. Orion briefly skips off Earth's atmosphere

After discarding its unneeded service module, which supplied electricity and power for nearly a month, Orion will do a daring skip maneuver off the edge of Earth's atmosphere. The capsule will use a bit of our protective envelope, along with associated lift, to skip just like a rock across the surface of a lake. This maneuver wasn't possible during the Apollo program, but advances in spacecraft navigation make that possible today.

"The skip entry will help Orion land closer to the coast of the United States, where recovery crews will be waiting to bring the spacecraft back to land," Chris Madsen, Orion guidance, navigation and control subsystem manager, said in a NASA statement.

"When we fly crew in Orion beginning with Artemis 2, landing accuracy will really help make sure we can retrieve the crew quickly and reduces the number of resources we will need to have stationed in the Pacific Ocean to assist in recovery."

The maneuver will also reduce the g-forces future Artemis program astronauts will experience once the Orion capsule is crewed. "Instead of a single event of high acceleration, there will be two events of a lower acceleration of about four g's each," NASA wrote in the same statement. "The skip entry will reduce the acceleration load for the astronauts so they have a safer, smoother ride."

3. Orion enters Earth's atmosphere

After the skipping maneuver, Orion will enter Earth's atmosphere at a blazing speed of 25,000 mph (40,000 km/h). At peak, its temperatures will soar to half of the sun's temperature, at 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,800 degrees Celsius), and really test out the Orion heat shield's ability to protect the spacecraft and any future passengers.

The heat shield is the largest of its type for astronaut missions, spanning 16.5 feet (5 meters) in diameter, according to NASA. The heat shield includes a strong titanium truss with a composite "skin" made of flexible carbon fiber, along with an ablative material to deliberately shed some of the shield off into the atmosphere to take stress off the rest of the system and carry heat away from the spacecraft.

4. Orion opens protective bay cover for parachutes

The capsule's parachutes must stay protected as Orion rides through the worst of re-entry, but as it gets closer to the ground they must pop out efficiently.

To do so, the spacecraft deploys a forward bay cover made out of titanium, which is both lightweight and extremely strong. Three 8-pound (4-kg) forward bay cover parachutes will ensure the cover's separation from the spacecraft.

"It's perfect for spaceflight, where every additional pound is more costly," Orion spacecraft maker Lockheed Martin notes of the cover technology.

"Parachutes aren't built to withstand the 5,000-degree Fahrenheit [2,600 degree-Celsius] temperatures upon re-entry — they would be too heavy and unable to generate enough drag to slow the spacecraft down — so the forward bay cover protects them until just the right moment."

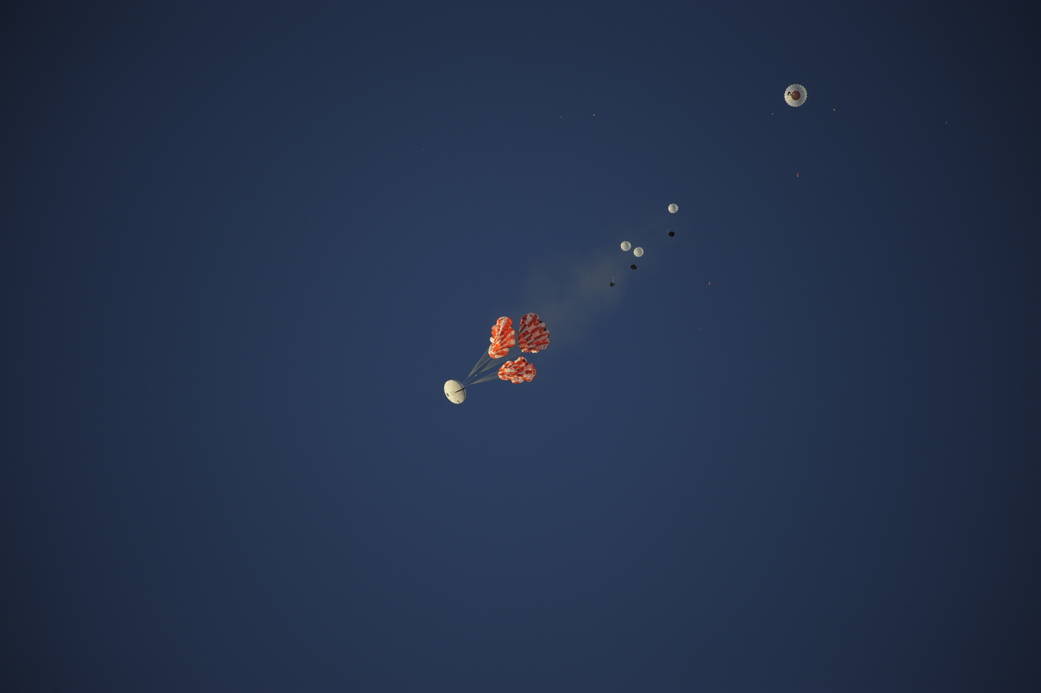

5. Orion opens drogue parachutes

Orion has several stages of parachutes to slow the spacecraft down. Following the three forward bay cover parachutes, at 25,000 feet (7,600 meters) will be the two drogue parachutes, which aim to slow Orion's speed to roughly 100 mph (160 km/h).

"Drogue parachutes are used to slow and stabilize the crew module during descent and establish proper conditions for main parachute deployment to follow," NASA writes of the technology.

The drogues are made of Kevlar/Nylon hybrid material and have a mass of about 80 pounds (36 kg) each. When inflated, each of the parachutes will be 100 feet (30 meters) long, between their attachment to the crew module and the top or crown.

6. Orion deploys pilot parachutes

Orion's drogue parachutes will then cut away, allowing for the three pilot parachutes to deploy. These parachutes are roughly 11 pounds (5 kg) in mass each and are also made of Kevlar/Nylon hybrid material.

The pilot parachutes will deploy when the Orion is roughly 9,500 feet (2,900 m) above the ground and traveling at 190 feet (130 m) per second.

This complicated parachute deployment illustrates a lot of technology, NASA says, including the fabric of the chutes, "cannon-like mortars" to fire the various rounds of parachutes at the right time, and fuses to unfurl the parachutes carefully and swiftly.

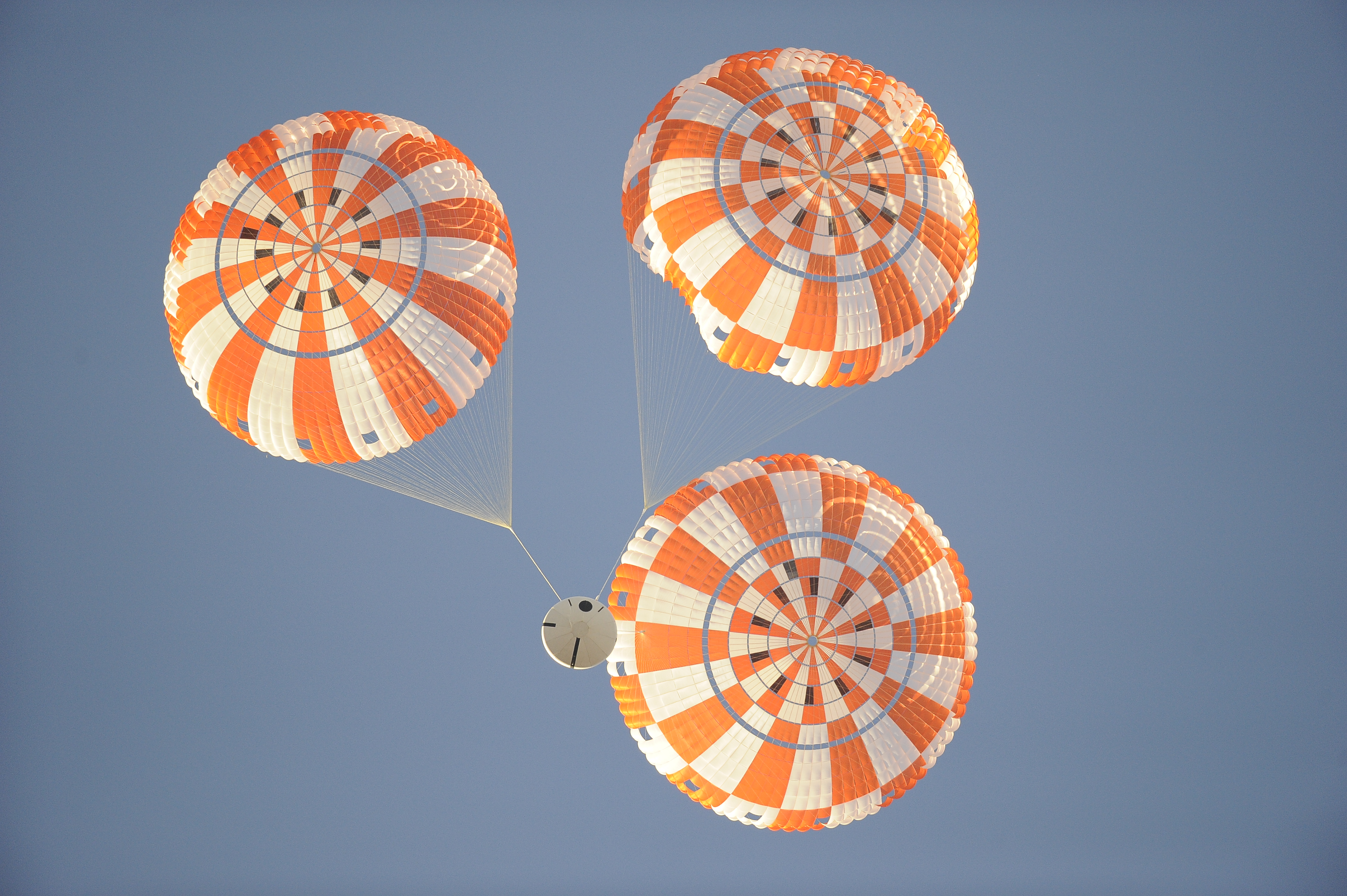

7. Orion opens main parachutes

The last set of Orion's 11 parachutes are the three main parachutes. The pilot parachutes will pull the mains out, which should deploy and slow Orion down to only 20 mph (32 km/h). Each main parachute is roughly 265 feet long (80 meters) from top to attachment.

"Orion's parachute system was designed with crew safety in mind: it can withstand the failure of either one drogue or one main parachute, and it can ensure a secure landing in an emergency," NASA says of the technology, noting the more than decade of ground and air tests to validate the system.

8. Orion splashes down in the Pacific Ocean

7. Orion splashes down

Assuming all the parachutes work according to plan, Orion will then splash down off the coast of San Diego at 12:40 p.m. EST (1740 GMT). The U.S. Navy and an exploration ground systems recovery team from NASA's Kennedy Space Center will work together to retrieve the spacecraft. The prime ship assigned to recovery operations is the USS Portland.

"Before splashdown, the team will head out to sea in a Navy ship. At the direction of the NASA recovery director, Navy divers and other team members in several inflatable boats will be cleared to approach Orion," NASA says of the recovery operations.

"Divers will then attach a cable to the spacecraft and pull it by winch into a specially designed cradle inside the ship's well deck ... open water personnel will also work to recover Orion's forward bay cover and three main parachutes."

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

-

newtons_laws Quote from article " The pilot parachutes will deploy when the Orion is roughly 9,500 feet (2,900 m) above the ground and traveling at 190 feet (130 m) per second. "Reply

There's something wrong with those quoted speeds 190 feet (130m) per second. 190 feet does not correspond to 130 m. At least one of those figures must be incorrect. -

glelder Reply

190 FPS equates to 130 MPH not 130 meters per second.newtons_laws said:Quote from article " The pilot parachutes will deploy when the Orion is roughly 9,500 feet (2,900 m) above the ground and traveling at 190 feet (130 m) per second. "

There's something wrong with those quoted speeds 190 feet (130m) per second. 190 feet does not correspond to 130 m. At least one of those figures must be incorrect. -

craig964 The article states that a "skip" reentry wasn't possible during Apollo. But apparently they did employ a skip entry. https://www.aulis.com/re-entrymatters.htmReply