Black holes could work as natural particle colliders to hunt for dark matter, scientists say

"The difference between a supercollider and a black hole is that black holes are far away, but nevertheless, these particles will get to us.”

To unlock the secrets of dark matter, scientists could turn to supermassive black holes and their ability to act as natural superpowered particle colliders. That's according to new research that found conditions around black holes are more violent than previously believed.

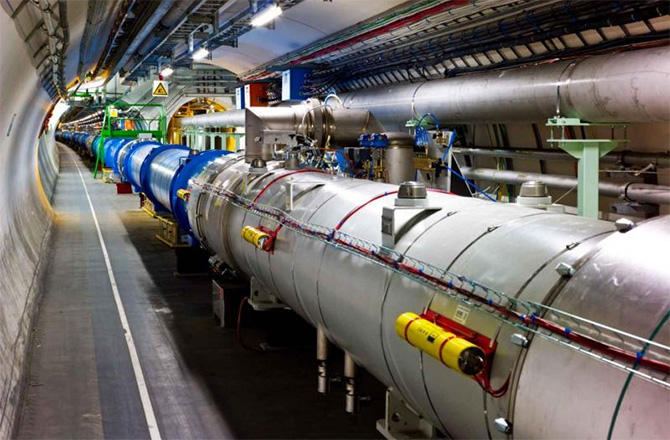

Currently, the most powerful particle accelerator on Earth is the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), but since it was used to discover the Higgs Boson in 2012, it has failed to deliver evidence of physics beyond the so-called "standard model of particle physics," including the particles that comprise dark matter.

That has led scientists to propose and plan even larger and more powerful particle colliders to explore this as-yet undiscovered country of physics. However, these particle accelerators are prohibitively expensive and time-consuming to build. Fortunately, the cosmos offers natural particle accelerators in the form of the extreme environments around supermassive black holes. We just need a little ingenuity to exploit them.

"One of the great hopes for particle colliders like the LHC is that it will generate dark matter particles, but we haven’t seen any evidence yet," Joseph Silk, study team member and a researcher at Johns Hopkins University, said in a statement. "That's why there are discussions underway to build a much more powerful version, a next-generation supercollider. But as we invest $30 billion and wait 40 years to build this supercollider, nature may provide a glimpse of the future in supermassive black holes."

Supermassive supercolliders

Dark matter is the mysterious stuff that seems to account for around 85% of all matter in the cosmos. That means the matter we understand — everything we see around us that's composed of atoms made of electrons, protons and neutrons — accounts for just 15% of stuff in the universe.

Dark matter remains frustratingly elusive because it doesn't interact with light, making it effectively invisible. This is why we know it can't be made of standard atoms because these particles do interact with light. That has spurred the search for new particles that could comprise dark matter, with a great deal of this effort conducted using particle accelerators like the LHC.

Human-made particle accelerators like the LHC allow scientists to probe the fundamental aspects of nature by slamming together particles like protons at near-light speeds. This creates flashes of energy and showers of short-lived particles. Within these showers, scientists hunt for hitherto undiscovered particles.

Test particles like protons are accelerated and guided toward each other within the LHC and other "atom smashers" using incredibly strong magnets, but supermassive black holes could mimic this process using gravity and their own spins.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Supermassive black holes with masses millions, or billions, of times that of the sun sitting at the hearts of galaxies are often surrounded by material in flattened clouds called "accretion disks." As these black holes spin at high speeds, some of this material is channeled to their poles, from where it is blasted out as near-light-speed jets of plasma.

This phenomenon could generate effects similar to those seen in particle accelerators here on Earth.

"If supermassive black holes can generate these particles by high-energy proton collisions, then we might get a signal on Earth, some really high-energy particle passing rapidly through our detectors," Silk said. "That would be the evidence for a novel particle collider within the most mysterious objects in the universe, attaining energies that would be unattainable in any terrestrial accelerator.

"We'd see something with a strange signature that conceivably provides evidence for dark matter, which is a bit more of a leap, but it's possible.”

The key to Silk and colleagues' recipe of supermassive black holes as supercolliders hinges on their discovery that gas flows near black holes can sap energy from the spin of that black hole. This results in the conditions in the gas becoming far more violent than expected.

Thus, around spinning supermassive black holes, there should be a wealth of high-speed collisions between particles similar to those created in the LHC here on Earth.

"Some particles from these collisions go down the throat of the black hole and disappear forever," Silk said. "But because of their energy and momentum, some also come out, and it’s those that come out which are accelerated to unprecedentedly high energies.

"It's very hard to say what the limit is, but they certainly are up to the energy of the newest supercollider that we plan to build, so they could definitely give us complementary results," Silk said.

Of course, catching these high-energy particles from supermassive supercolliders many light-years away will be tricky even if the team's theory is correct. Key to this detection could be observatories already tracking supernovas, black hole eruptions and other high-energy cosmic events.

"The difference between a supercollider and a black hole is that black holes are far away," Silk concluded. "But nevertheless, these particles will get to us."

The team's research was published on Tuesday (June 3) in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.