Hubble Telescope sees wandering black hole slurping up stellar spaghetti

"I think this discovery will motivate scientists to look for more examples of this type of event."

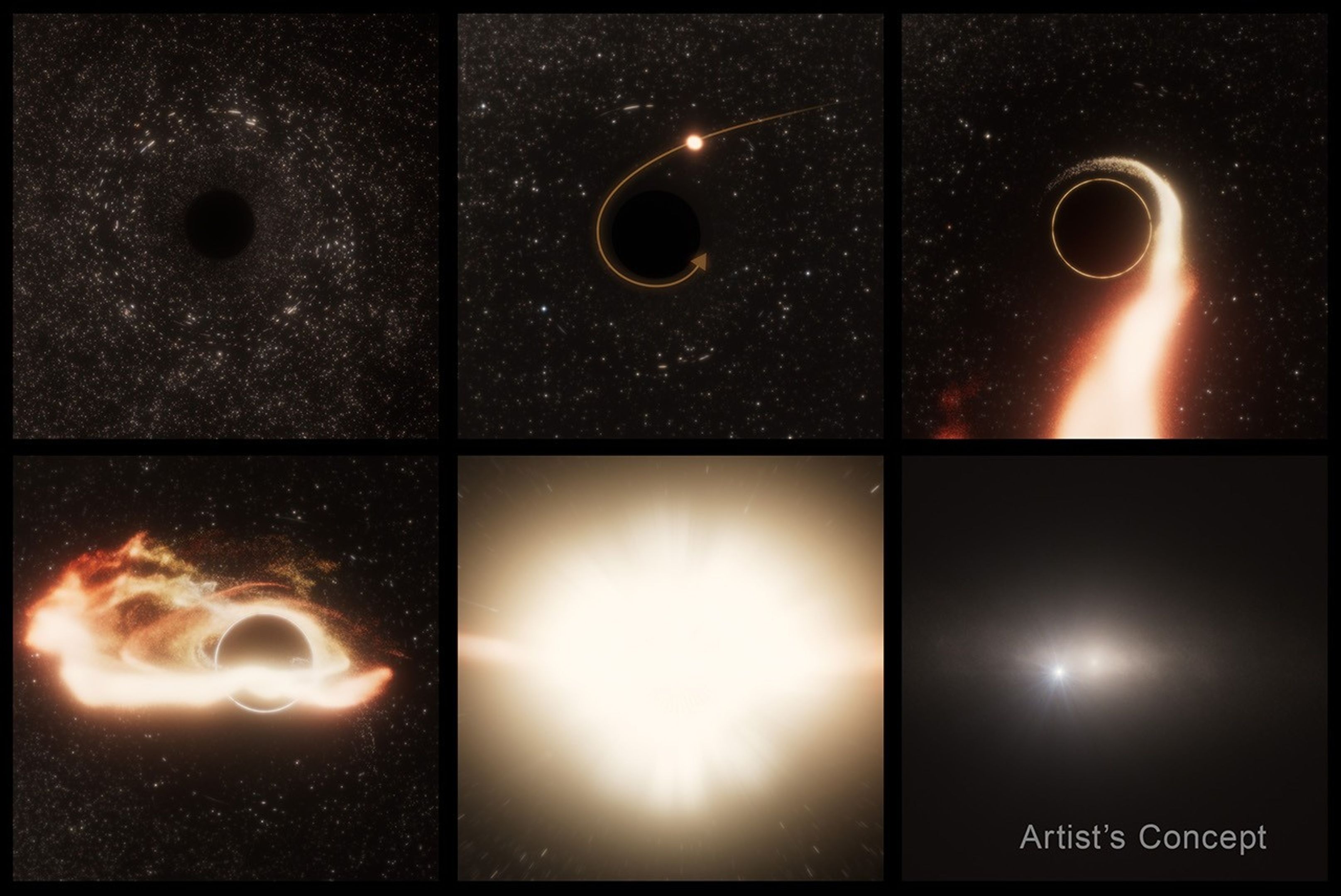

Astronomers have caught a black hole far from the center of its home galaxy ripping a star to shreds — providing, for the first time, direct evidence of a rogue supermassive black hole in action.

The event, named AT2024tvd, took place approximately 600 million light-years from Earth. Despite weighing about a million times the mass of our sun, the black hole wasn't found at the center of its host galaxy, where such giants typically reside. It marks the first known instance of an "off-center" tidal disruption event (TDE), a phenomenon where a star is stretched and torn apart — or spaghettified — by a black hole's immense gravity.

Astronomers say the find opens the door for tracking down other rogue TDEs. "I think this discovery will motivate scientists to look for more examples of this type of event," Yuhan Yao, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, who led the study, said in a NASA statement.

The sudden, bright flare from the event was picked up by the Zwicky Transient Facility, a sky-surveying optical camera mounted on a telescope at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego. Follow-up observations by the Hubble Space Telescope revealed that this black hole lies 2,600 light-years from the galaxy's core, where a much larger black hole resides — a behemoth 100 million times the mass of the sun.

The presence of two massive black holes in a single galaxy isn't unexpected, astronomers say. Most large galaxies contain at least one supermassive black hole at their center. Because galaxies frequently collide and merge over cosmic timescales, astronomers have long speculated that some galaxies might harbor multiple black holes, at least until they eventually collide and merge into an even larger black hole.

These hidden giants typically remain quiet, only revealing themselves when they consume nearby stars or gas clouds, producing a brief burst of light. But catching these black holes in action is incredibly rare. Astronomers estimate that a massive black hole consumes a star approximately once every 30,000 years.

These events "hold great promise for illuminating the presence of massive black holes that we would otherwise not be able to detect," Ryan Chornock, a professor of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, said in the same statement. "Theorists have predicted that a population of massive black holes located away from the centers of galaxies must exist, but now we can use TDEs to find them."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While the presence of two supermassive black holes in a single galaxy isn't surprising, the fact that this one is not gravitationally bound to the galaxy's core raises intriguing questions about its history. For one, astronomers are uncertain how this "rogue" black hole ended up so far from the center. One theory is that it was ejected during a violent cosmic interaction involving multiple black holes. Another possibility is that it came from a smaller galaxy that merged with the larger one over a billion years ago.

If this rogue black hole was indeed a remnant of a past merger, it may eventually drift inward and merge with the larger black hole at the galaxy's center, according to the statement. Such a merger would release powerful gravitational waves, ripples in spacetime that could one day be detected by future space-based observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), scheduled for launch in 2035.

This research is described in a paper accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.