The US isn't prepared for a big solar storm, exercise finds

We need more satellites to keep tabs on incoming clouds of solar particles.

A first-of its-kind space weather "tabletop" exercise has revealed major weaknesses in America's preparedness for severe solar storms.

In May 2024, participants representing local and national government agencies gathered at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, and at a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) site in Denver, Colorado, to learn how ready they were for a major solar storm. Results of the unique exercise they conducted have recently been released in a new report.

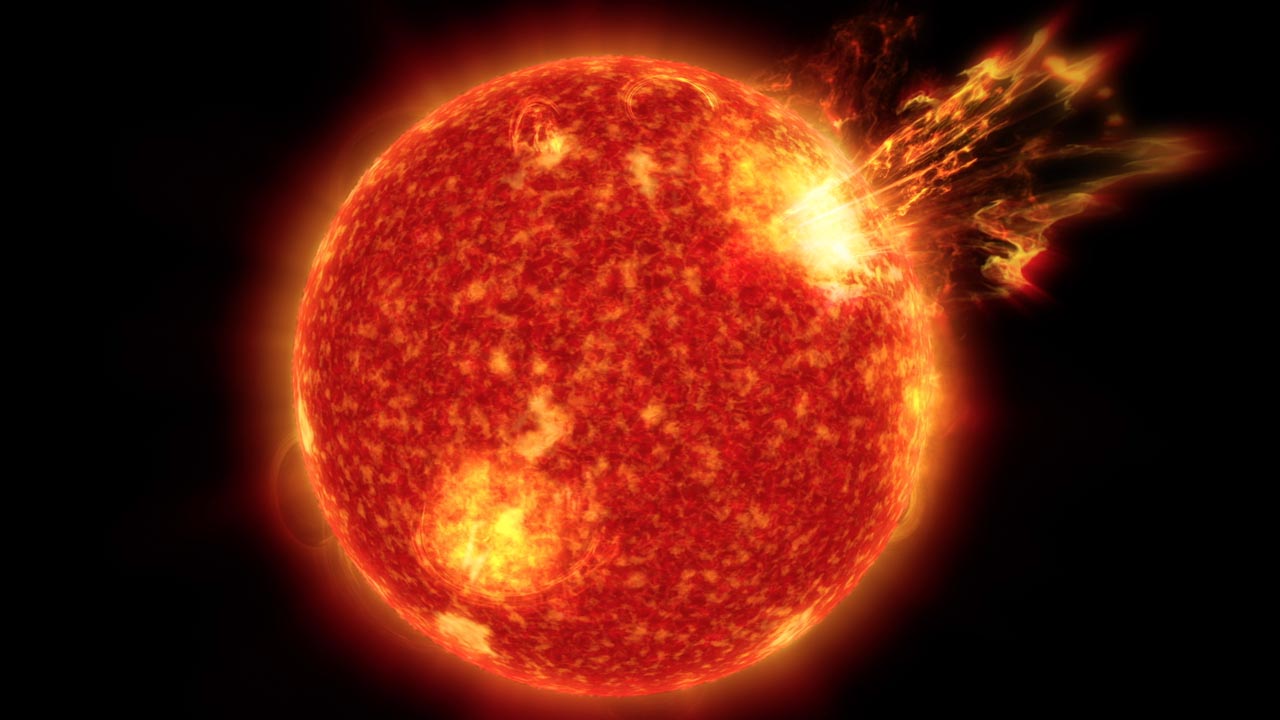

The exercise, which lasted two days, had the participants pretend that the sun expelled several giant coronal mass ejections (CMEs), which were hurtling toward Earth. CMEs are eruptions of strongly magnetized plasma from the sun's upper atmosphere, the corona. These giant clouds of charged particles take several days to reach Earth, but when they do, they can wreak havoc with the planet's magnetic field and the upper atmosphere.

The geomagnetic storms caused by these interactions can trigger power blackouts, disrupt satellite signals and damage satellite electronics. They can also subject astronauts in space to high doses of radiation. Although super-powerful geomagnetic storms only hit once every few decades, the disruption they can cause to our technology-dependent society is significant. Yet, the participants of the exercise, which was organized by the Space Weather Research and Operations Center (SWORM) and the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC), found that a lack of communication protocols and insufficient measurements from space and on the ground hamper effective response to such incidents.

The scenario explored in the exercise asked the participants to time travel to January 2028. NASA's Artemis 4 mission is orbiting the moon with two astronauts aboard, and their two colleagues have just landed on the surface. At the same time, a giant sunspot has emerged on the solar surface and sent several flares and CMEs in Earth's direction.

The exercise made the participants aware of significant limitations of current space weather forecasting capabilities, according to the report, which was published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in mid-April.

As the hypothetical CMEs neared the planet, the participants realized that the lack of measurements prevented accurate modelling and forecast of impacts, which in turn therefore complicated effective decision making.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The biggest problem, the participants realized, was the fact that, although a CME takes up to three days to reach the planet, the scope of its impact is dependent on the orientation of the magnetic field in the plasma it carries.

When the cloud and Earth's magnetic field meet with the same poles, they mostly repel each other. When opposite poles collide, however, an enormous energy exchange follows that can wreak havoc on Earth and in orbit. The magnetic field orientation of the incoming cloud, however, is only known about 30 minutes before the CME hits, when the cloud passes the Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 1, a gravitationally stable spot about 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth where several sun-observing spacecraft are located.

The report highlights the need to deploy more satellites to improve the forecasters' "ability to predict events, enhance real-time data collection, improve forecasting models and provide earlier warnings."

In the hypothetical scenario, the sequence of powerful eruptions led to widespread power blackouts, disruption of satellite and radio communication and degradation of GPS positioning, navigation and timing services. In a real-life situation, the primary impacts would lead to serious disruptions in many sectors, including aviation, emergency response and health care, as hospitals would have to rely on back-up power generators for days.

In space, satellites deviated from their trajectories due to the changes in air density caused by the sudden heating triggered by the energetic processes. As a result, satellite trackers on the ground were unable to ascertain satellite positions and determine collision risk. NASA experts, at the same time, were trying to determine the risk to the astronauts and decide on emergency measures.

As the hypothetical solar storm worsened, the exercise participants quickly became overwhelmed with information. The report recommended that government authorities develop communication and messaging templates like those used in other natural disaster situations such as hurricanes. The participants concluded that government agencies across the board need to cooperate to prepare for significant space weather events.

Coincidentally, the exercise took place at the same time as the Gannon Storm, the most powerful solar storm in 20 years, which meant many of the problems studied could be, on a smaller scale, verified in practice.

The Gannon Storm hit Earth on May 10, 2024, and triggered a mass migration of satellites that rendered Earth's orbit unsafe for days. It also caused local power outages and widespread radio and satellite communication blackouts. Still, the Gannon Storm was nowhere near as potent as the most energetic solar storm to take place in recorded history — the 1859 Carrington Event.

Since the current solar cycle — the 11-year ebb and flow in the number of sunspots and eruptions — has only just reached its peak, scientists worry that more solar drama is on tap in the coming years.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.