Tiny galaxies may have helped our universe out of its dark ages, JWST finds

"These small galaxies punch well above their weight."

Evidence continues to assemble that dwarf galaxies played a larger role in shaping the early universe than previously thought.

Astronomers analyzing data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have uncovered a population of tiny, energetic galaxies that may have been key players in clearing the cosmic fog that shrouded the universe after the Big Bang.

"You don't necessarily need to look for more exotic features," Isak Wold, an assistant research scientist at the Catholic University of America in Washington D.C., told reporters during the 246th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Alaska. "These tiny but numerous galaxies could produce all the light needed for reionization."

About 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe cooled enough for charged particles to combine into neutral hydrogen atoms, creating a thick, light-absorbing fog, an era known as the cosmic dark ages. It wasn't until several hundred million years later, with the birth of the first stars and galaxies, that intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation began reionizing this primordial hydrogen. That process gradually cleared the dense fog, allowing starlight to travel freely through space and illuminating the cosmos for the first time.

For decades, astronomers have debated what triggered this dramatic transformation. The leading candidates included massive galaxies, quasars powered by black holes, and small, low-mass galaxies. New data from the JWST now points strongly to the smallest contenders, suggesting these tiny galaxies acted like cosmic flashlights lighting up the early universe.

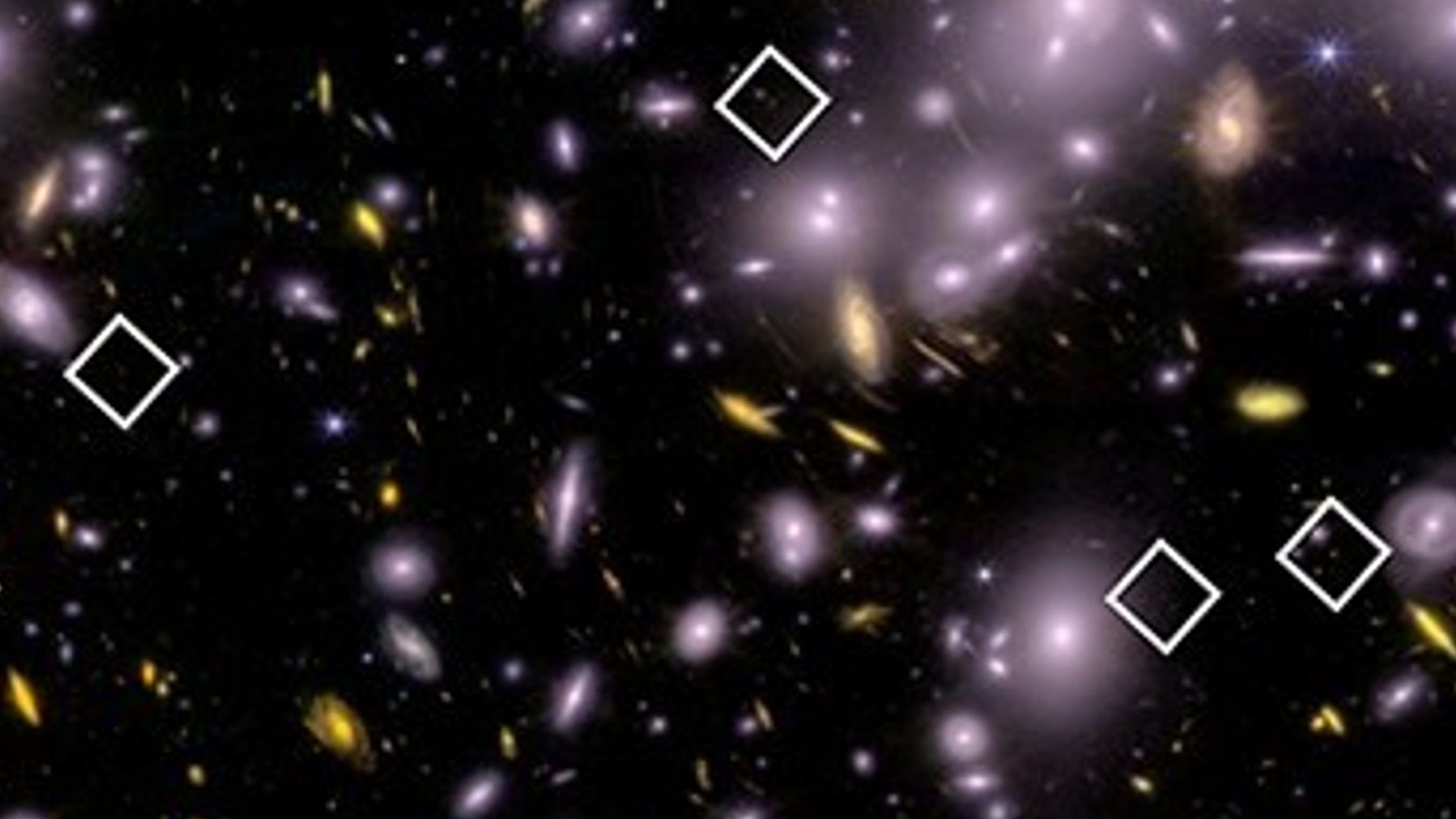

To identify these early galaxies, Wold and his colleagues focused on a massive galaxy cluster called Abell 2744, or Pandora's Cluster, located about 4 billion light-years away in the constellation Sculptor. The immense gravity of this cluster acts as a natural magnifying glass, bending and amplifying light coming from much more distant, ancient galaxies behind it. Tapping into this quirk of nature, combined with the JWST's powerful instruments, the researchers peered nearly 13 billion years back in time.

Using the JWST's Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), the team searched for a specific green emission line from doubly ionized oxygen, a hallmark of intense star formation. This light was originally emitted in the visible range but was stretched into the infrared as it traveled through the expanding universe, according to a NASA statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The search yielded 83 tiny, starburst galaxies, all vigorously forming stars when the universe was just 800 million years old, around 6% of its current age.

"Our analysis [...] shows they existed in sufficient numbers and packed enough ultraviolet power to drive this cosmic renovation," Wold said in the statement.

Today, similar primitive galaxies, such as so-called "green pea" galaxies, are rare but known to release roughly 25% of their ionizing UV radiation into surrounding space. If early galaxies functioned in the same way, Wold said, they would have generated enough light to reionize the hydrogen fog and make the universe transparent.

"When it comes to producing ultraviolet light, these small galaxies punch well above their weight," he said in the statement.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.