Astronomers may have solved the mystery of Betelgeuse's bizarre brightness drop.

In the fall of 2019, Betelgeuse — one of the brightest and best-known stars in the sky — began dimming dramatically. By February 2020, it had lost about two-thirds of its normal luminosity.

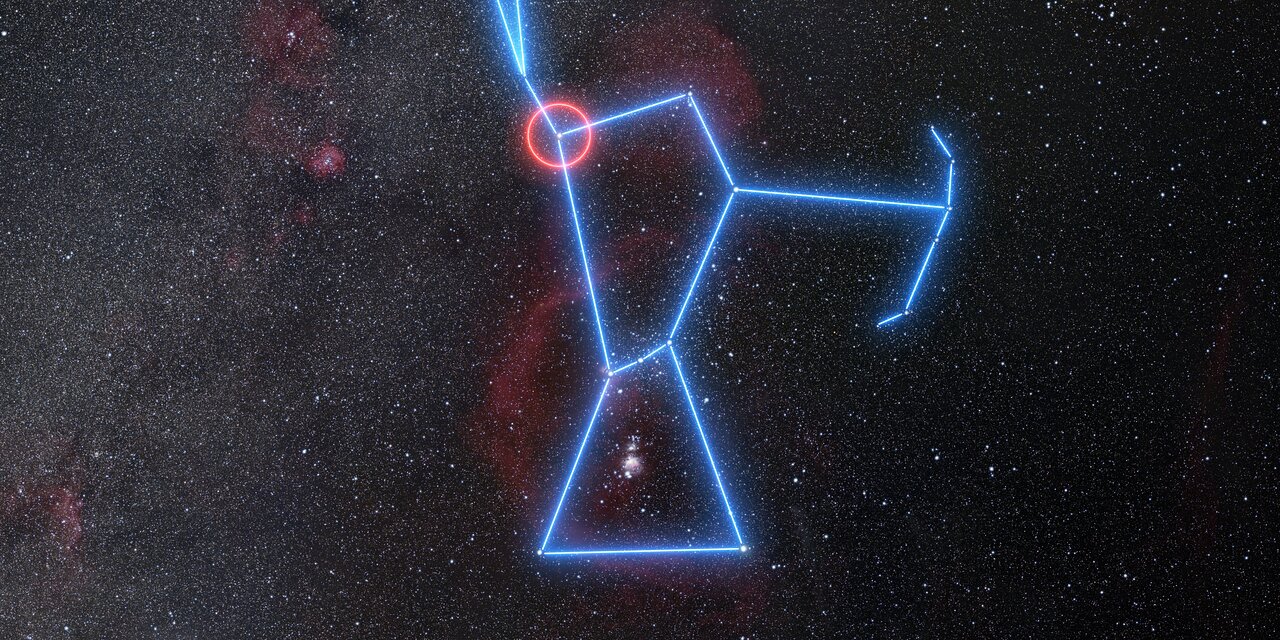

Betelgeuse, which forms the shoulder of the constellation Orion (The Hunter), is a bloated red supergiant, a massive star that will die in a violent supernova explosion in the relatively near future. So some astronomers speculated that this "Great Dimming" might be the beginning of Betelgeuse's death throes, and that the star could soon go boom.

Related: The brightest stars in the sky: A starry countdown

But that didn't happen. Betelgeuse bounced back to its expected brightness levels by April 2020, bolstering the more prosaic explanations for the Great Dimming. Perhaps Betelgeuse simply experienced a transient cooling episode, for example. Or maybe its light was temporarily blocked by a cloud of dust.

A new study supports the dust idea but suggests that stellar cooling played a role as well.

Researchers led by Miguel Montargès, an astrophysicist at the Paris Observatory and Université PSL, studied Betelgeuse before and during the Great Dimming, using multiple instruments installed at the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team combined these observations with detailed modeling of Betelgeuse, which is about 11 times more massive than Earth's sun but 900 times more voluminous. (If you plunked Betelgeuse down where our sun sits, the supergiant would engulf Mercury, Venus, Mars and Earth.)

Together, the data sets suggest a likely Great Dimming scenario, which comports with previous research based on Hubble Space Telescope observations. Sometime before astronomers started noticing the dimming, Betelgeuse ejected a huge cloud of gas. Then, in the fall of 2019, convective cooling in the star's atmosphere and its regular pulsations — Betelgeuse expands and contracts on a roughly 400-day cycle — dropped the temperature in the cloud's surroundings, allowing much of the gas to condense quickly into dust. And this dust blocked much of Betelgeuse's light as seen from Earth.

"Our results confirm that the Great Dimming is not an indication of Betelgeuse’s imminent explosion as a supernova," Montargès and his colleagues wrote in the new study, which was published online today (June 16) in the journal Nature.

However, "some red supergiants may show little or no sign of their impending core collapse, years to weeks before it happens," they added. "Therefore, although the current mass-loss behavior of Betelgeuse does not appear to forebode its demise, it remains possible that it may explode without warning."

The new research could have applications beyond merely understanding Betelgeuse, which lies about 720 light-years from Earth (though calculations of its distance vary a bit), astronomer Emily Levesque wrote in an accompanying "News and Views" piece in the same issue of Nature.

"This exquisitely detailed study of Betelgeuse’s unexpected behavior lays the groundwork for unravelling the properties of an entire population of stars," wrote Levesque, who's based at the University of Washington. "Next-generation facilities focused on monitoring stellar brightness over time, or on studying the signatures of dust in the infrared spectra of stars, could prove invaluable for expanding the lessons learnt here."

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.