Black Hole Photos Could Get Even Clearer with Space-Based Telescopes

The first-ever photo of a black hole amazed people across the world. Now, astronomers are aiming to take even sharper pictures of these enigmatic structures by sending radio telescopes into space.

The historic photo became public on April 10, when the worldwide research collaboration known as Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) unveiled the hazy but nevertheless incredible photo of the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87.

Astronomers at Radboud University in the Netherlands have recently shared their plans to work with the European Space Agency (ESA) and others to get a better look at black holes by placing two to three satellites in a circular orbit around Earth. The concept is called the Event Horizon Imager (EHI).

Related: The Future of Black Hole Photography: What's Next for the Event Horizon Telescope

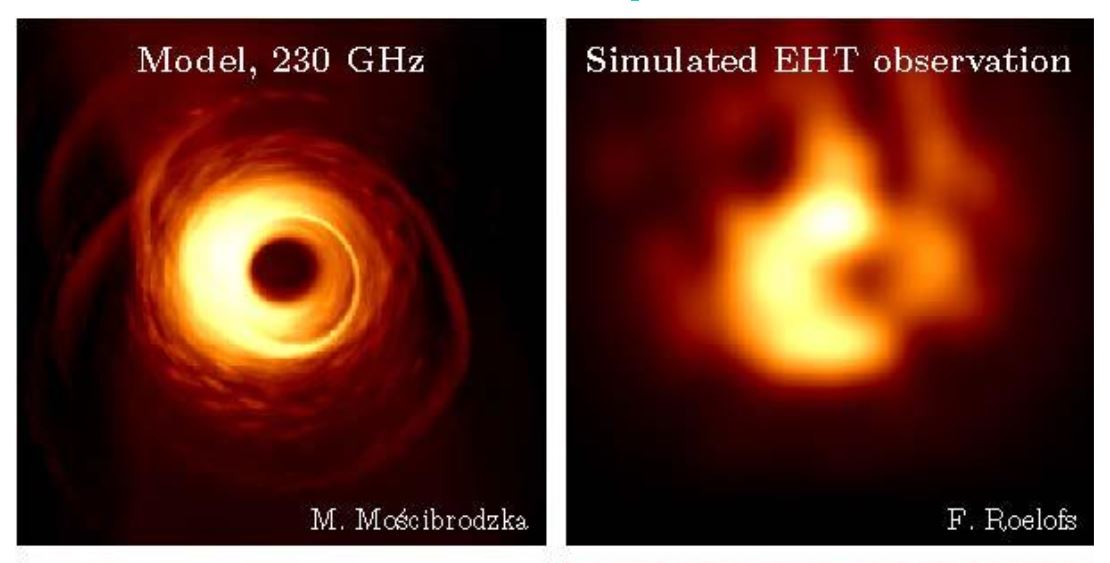

The resolution of a radio image is limited by the size of the telescope that receives the signal, and that's why EHT used a network of dish telescopes around the world to essentially turn Earth into a planet-size virtual telescope. By expanding the distances between the radio observations, astronomers could someday present the public with a clearer, more detailed view of a black hole, researchers said in a statement from Radboud University.

"There are lots of advantages to using satellites instead of permanent radio telescopes on Earth, as with the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT)," Freek Roelofs, a researcher at Radboud University and lead author of an article describing this potential project, said in the statement.

"In space, you can make observations at higher radio frequencies, because the frequencies from Earth are filtered out by the atmosphere," Roelofs added. "The distances between the telescopes in space are also larger. This allows us to take a big step forward. We would be able to take images with a resolution more than five times what is possible with the EHT."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A crisper look would offer more than just aesthetics. According to the statement, imagery by EHI could be used to test Einstein's Theory of General Relativity in greater detail, because ''you can take near perfect images to see the real details of black holes,'' Heino Falcke, radio astronomer at Radboud University and co-author on the new work, said in the statement. ''If small deviations from Einstein's theory occur, we should be able to see them."

EHI would initially function apart from EHT, but a hybrid system to combine space observations with those taken from the ground could be a possibility.

The plans are detailed in a forthcoming article in the scientific journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

- Google Doodle Celebrates the 1st Black Hole Image by the Event Horizon Telescope

- What Exactly Is a Black Hole Event Horizon (and What Happens There)?

- The Best Hubble Space Telescope Images of All Time!

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.