Sometimes looking up at a starlit sky can almost be like playing a game of "connect the dots." Distinctive groupings of stars forming part of a recognized constellation outline, or lying within their boundaries, are known as asterisms, or star patterns.

Ranging in apparent size from sprawling, naked-eye figures to minute stellar settings requiring a telescope to be seen, these celestial figures are found in every quarter of the sky and at all seasons of the year.

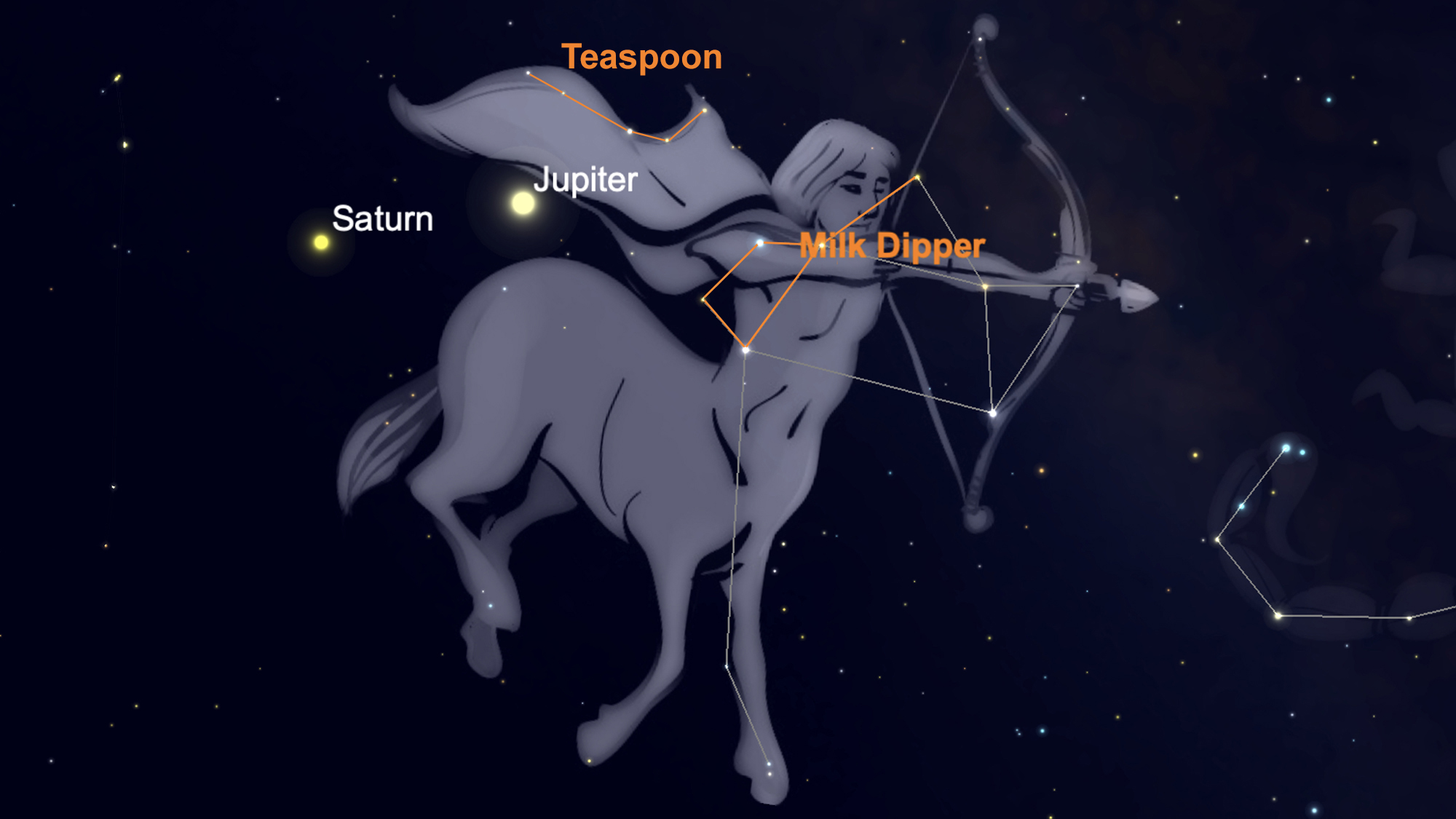

The larger asterisms — ones like the Big Dipper in Ursa Major and the Great Square of Pegasus — are ironically often better known than their host constellations. Sagittarius can actually be considered to be three different star patterns in one: the "traditional" archer — a constellation, but also an asterism portraying an upside-down milk dipper, complete with a teapot, teaspoon and a lemon slice!.

Related: Constellations of the night sky: famous star patterns explained

An excellent guide to the naked-eye asterisms is provided by William Tyler Olcott, R. Newton and Margaret Mayall's "Field Book of the Skies" (G.P. Putnam's Son, 1954), which points out many such objects on a constellation-by-constellation basis.

Another useful reference is the "Field Guide to the Stars and Planets" by Donald Howard Menzel (Houghton Mifflin, 1964). This contains a roster of more than two dozen asterisms (including the Pleiades, Hyades and Beehive star clusters), together with wide-angled sky photos showing many of them.

Size matters ... the smaller, the better

With asterisms, it seems the smaller they are the more stunning their visual impact upon the observer. This is especially true of those encountered while sweeping the sky with large-aperture binoculars and wide-field telescopes, many of which have surprising (and in some cases downright unbelievable) shapes. Among these are chains, loops, and arcs of stars, triangles, circles, squares and arrows, and even some that look like letters, numbers and other familiar terrestrial objects.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Despite their endless charm and variety, these small asterisms are totally overlooked by nearly all observing guidebooks and are little-known to most stargazers. The sky is literally studded with uncatalogued specimens, particularly in and near the Milky Way itself.

There is perhaps no more striking example of this type of asterism than one now well placed for evening viewing in the otherwise faint constellation of Vulpecula, the little fox, a constellation resembling not a fox, but a cowboy boot, another asterism. The Vulpecula constellation contains a small asterism called Collinder 399, or "Brocchi's cluster," but more popularly known as the "Coat Hanger."

To find it, locate the famous "Summer Triangle" — an asterism in its own right — formed by the brightest stars of three constellations: Vega in Lyra, the lyre; Altair in Aquila, the eagle; and Deneb in Cygnus, the swan. Of the three, Altair is the easiest to identify because it is flanked by a fainter star on either side of it. The star to the upper right of Altair is Tarazed, while the star to the lower left is Alshain. Use these three stars to point your way toward the Coat Hanger; they measure just shy of 5 degrees apart.

Now, an imaginary line directed upward through these three stars, for approximately twice the distance (10 degrees) between them will point directly at the Coat Hanger, projected against the glittering backdrop of the summer Milky Way.

Using just your eyes, this unusual asterism appears as nothing more than a blur of light involving the stars 4, 5 and 7 Vulpeculae arranged in the shape of a tight triangle. Binoculars, however, dramatically transform this group into an amazing sight: a chain composed of four sixth-magnitude and two seventh-magnitude stars strung out in a line and joined at its center by a conspicuous loop of four stars, together forming an inverted coat hanger in the sky!

Celestial tribute to my aunt

I can still remember when I was a sophomore in high school, spending a few days in mid-August at my aunt and uncle's house in Mahopac, New York, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) north of New York City. Back then, light pollution was much less of a factor than it is now and the night skies were very dark. In between watching for Perseid meteors I spent time with binoculars scanning up and down the Milky Way. That's when I stumbled across the Coat Hanger. I was quite amazed because none of the astronomy books or guides that I had read made any mention of it.

Initially, I did not identify it as an upside-down coat hanger. Instead, I thought the chain of stars and adjacent loop resembled a ladle, so I named it "Irma's ladle" in honor of my aunt. It wasn't until later, after doing some research that I discovered that during the 1920s that the well-known variable star observer, Dalmero Francis Brocchi (1871-1955), a resident of Seattle, designed a star chart depicting the region of the sky around Vulpecula, revealing this cluster. Hence in some circles, the cluster is named for him. In Collinder's star catalogue, which was drawn-up in 1931, it is cluster No. 399, thus its "official" designation, Collinder 399.

And yet as I mentioned earlier, Brocchi's Cluster is never mentioned in most astronomy books, but it is the brightest of all the star clusters in that part of the sky. Nonetheless, whenever I look at it, I still think of that warm summer night many years ago when I first saw it and named it for my Aunt Irma.

The sight of this remarkable star cluster may well move you to seek out similar stellar curiosities. Why not leisurely scan the sky some night with binoculars and take note of any unusual star patterns you might run across? Such a compilation might end up being of some interest to other observers. Who knows? You just might turn up some overlooked asterism even more striking than the Coat Hanger itself!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.