Whenever I give star talks, either under the artificial sky of a planetarium or from a dark, rural location where the actual nighttime firmament can be seen in all of its glory, I recite to my audience words that were penned by the 19th-century American philosopher and poet Ralph Waldo Emerson: "If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which had been shown!"

In other words, if the stars were to appear for just a single night in a millennium, how likely would extensive preparations be made for viewing such an amazing sight — and what stories would later be told of this magnificent view?

Alas, for many who live in large, metropolitan areas, surrounded by smoke and haze and bright lights, it is easy to forget the beauty of the night sky. For most of us, it is rare to travel out into the country, far from artificial lights, to enjoy its grandeur. Our distant ancestors, however, weren't so blinded by the lights of civilization; they could see the sky on any clear night from wherever they were and they told stories filled with imagination, using the patterns of stars for illustration.

Related: Best night sky events (stargazing maps)

A sky filled with parables

These patterns — the constellations — are the legacy of those imaginations. The constellations that we know today have come down to us from their origins in the eastern Mediterranean and in the Middle East. The star lore accumulated by those early stargazers helped to bring the stars to life. It made the constellations into real figures, and the stars into patterns full of meaning. The apparent senseless jumble of bright stars soon became a picture book in which to read the stories of many centuries ago.

Much of the understanding and thought of early astronomers was told not in the knowledge of science but of mythology. Many fables telling of the stars that seem to us nothing more than fantasy might have been a way to try and explain the thoughts, myths and religions of ancient humans. But the charm of the stories lies in the stories themselves, and while seemingly odd to us, they were very real to our predecessors and were often apt, imaginative and well-thought-out.

Astronomy of the Eastern world

While most stories about the night sky had their origins from the Roman, Greek and Egyptian cultures, we should not overlook China, Korea and Japan — cultures that had observers who assiduously watched the heavens and kept careful records of what they saw. For example, stars that "flew" or "fell like the weaving," were descriptions of meteor showers, and "broom" or "sweeping stars" were identified as comets.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Chinese characters — called ideograms — were later adopted by the Japanese when they established a written language during the first few centuries A.D., in spite of the complete difference between the two languages. Ideograms for the sun and moon demonstrated how the Chinese adopted a building-block principle to convey abstract ideas. The symbol for "bright" for instance, was to place both the sun and moon symbols together, side by side.

Different cultures from Eastern countries have their own myths and stories of the night sky.

The princess and the cow herder

July is associated with one of the leading Far East legends about the stars.

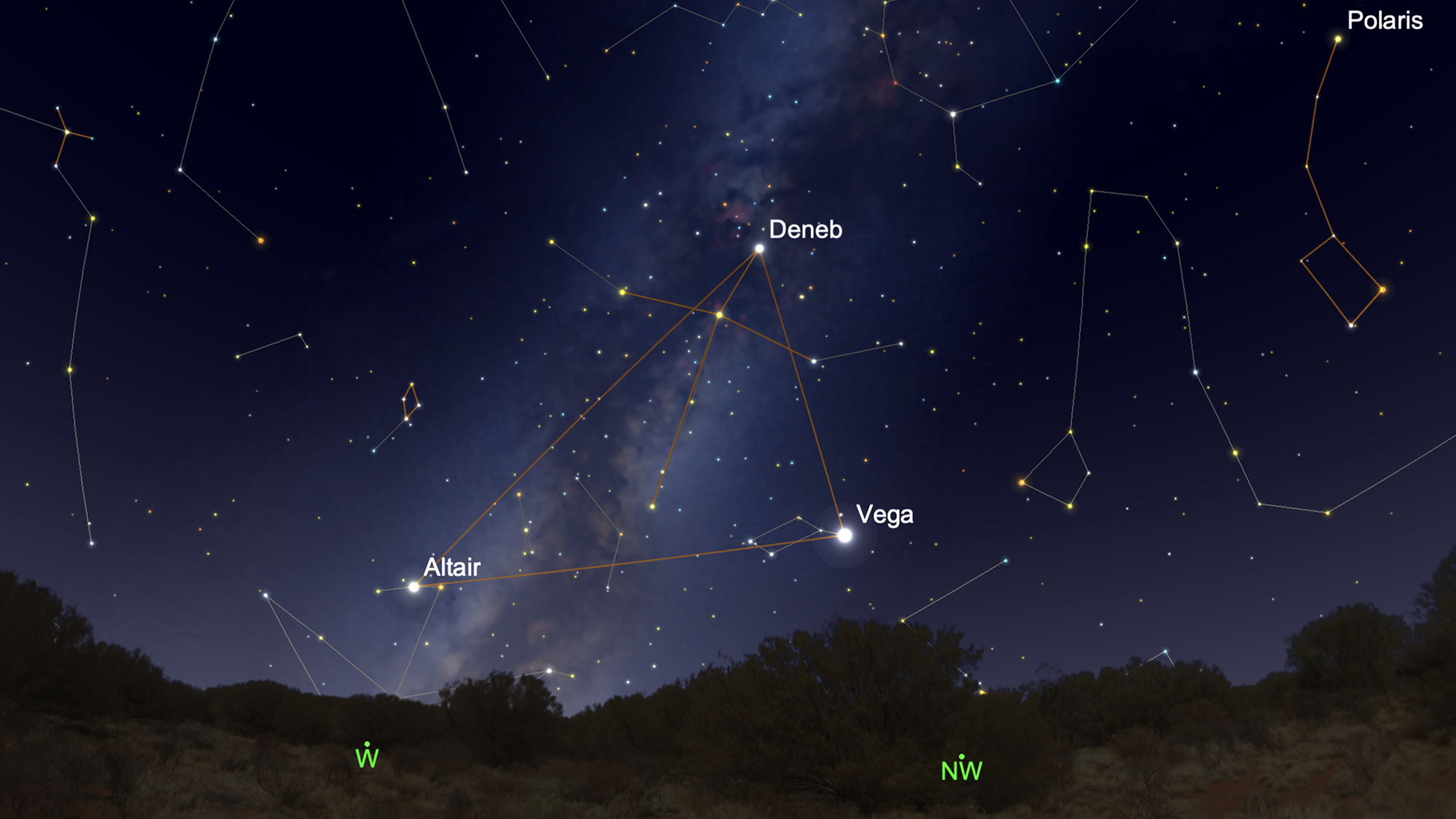

It involves two of the brightest stars of the summertime sky, Vega and Altair. They represent two star-crossed lovers who are separated by the Heavenly River — what we call the Milky Way. In the ancient Chinese story, Vega is Princess Tchi-Niu, daughter of the sun god and an exceptionally skilled weaver and creator of beautiful garments. Altair is Kien-Niou, the royal cow herder who watches over the imperial livestock.

From her side of the river, the princess admired the herdsman with increasing pangs of passion, so finally her father arranged for a meeting. One thing, of course, led to another, and the princess and the cow herder were wed.

But there was a serious drawback to this union, as Tchi-Niu and Kien-Niou spent all their waking hours with each other and neglected their responsibilities. The weaving that many depended on the princess for never got done, and the imperial cattle were neglected and began to scatter.

The sun god warned both his daughter and son-in-law more than once that they had to attend to their duties, but finally, when all else failed he separated the pair by returning his daughter to the other side of the river. The princess begged her father for another chance, and after many tearful pleas he finally broke down and offered a concession. The couple, said the sun god, could be reunited, but only for a single night each year — on the seventh day of the seventh month (July 7).

And there was a catch: This annual rendezvous could only take place if the weather was clear.

Same time next year

In Japan, this cast of characters has different names. The sun god is Tentei, the princess is known as Orihime, the cow herder is called either Kengyu or Hikoboshi, and the Heavenly River is Amanogawa. July 7 eventually evolved into a special children's holiday called Tanabata, or Seventh Evening, in which youngsters offer prayers for clear weather so that the couple can get together. Some versions of this story have a flock of magpies forming a bridge across the river to facilitate the reunion. For centuries there was a tradition that children who caught sight of a solitary magpie on the critical day would throw stones at it in the belief that the bird wasn't fulfilling its duty.

It is said that if it rains on Tanabata, the rain is called "The tears of Orihime and Hikoboshi," and the magpies can't come because of the rise of the river, forcing the lovers to wait until next year to meet.

Better luck nest time!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.