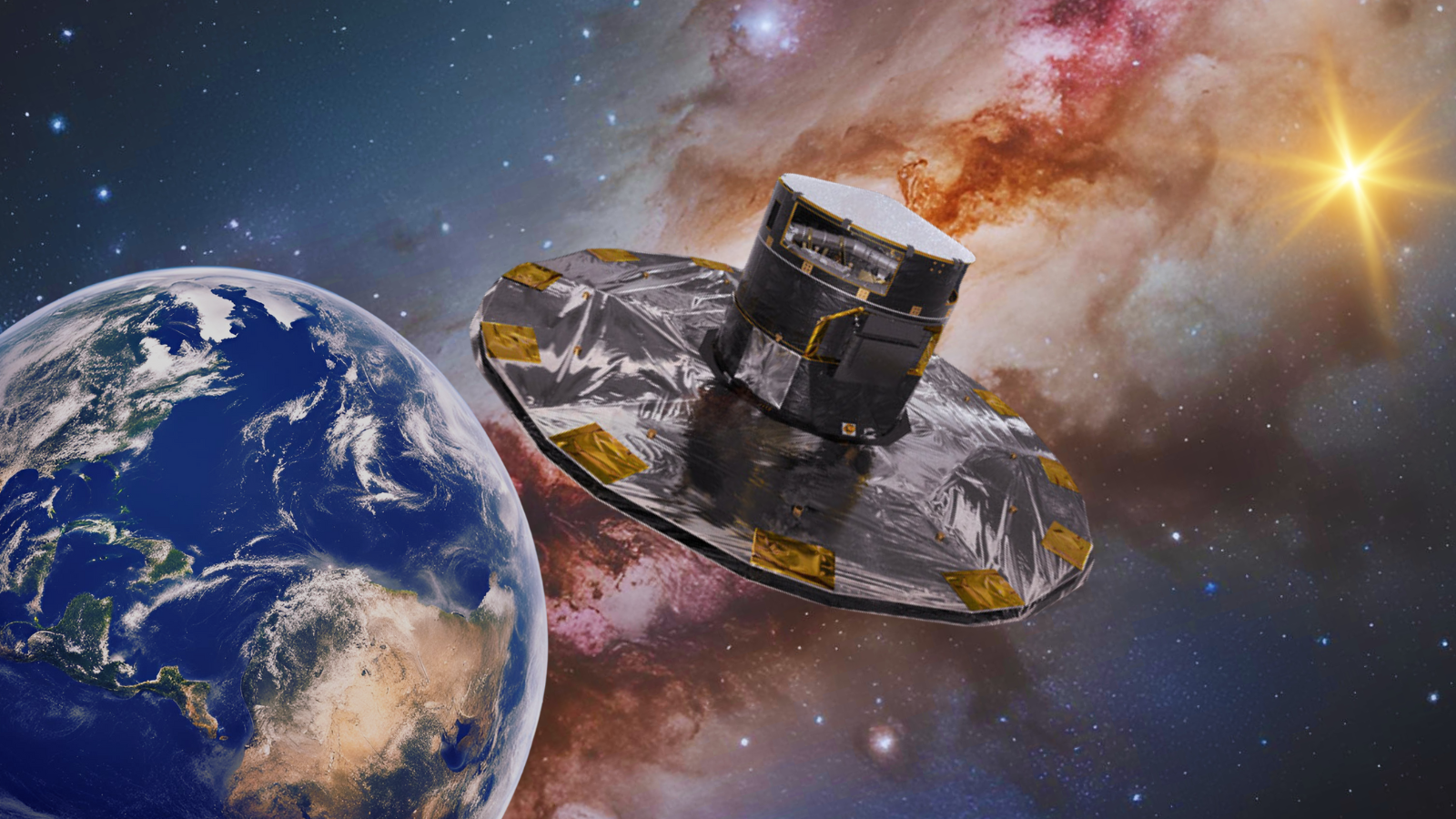

Goodnight, Gaia! ESA spacecraft shuts down after 12 years of Milky Way mapping

"I expect Gaia's best results are still to come."

Night has fallen for the star-tracking European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft, Gaia. The mission, which has been mapping the Milky Way for the last 12 years, shut down science operations on Wednesday (Jan. 15).

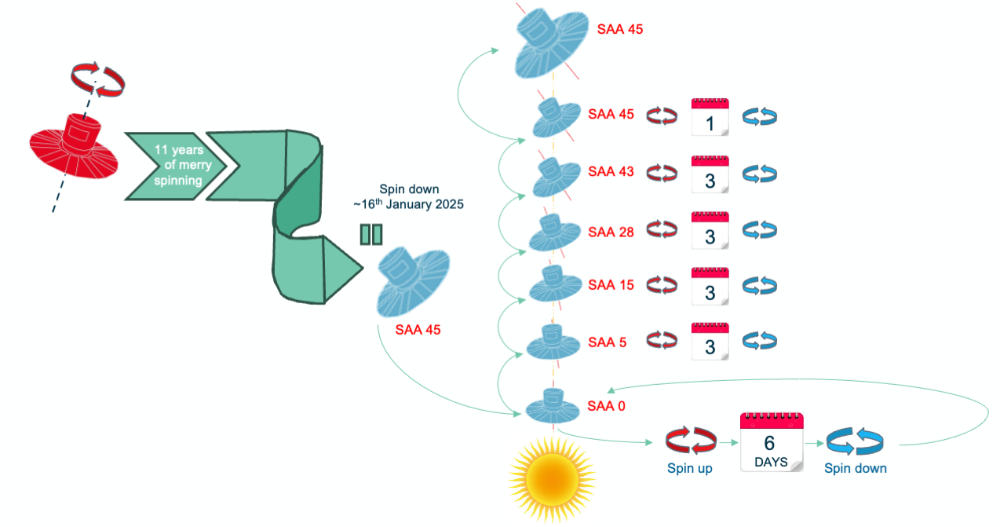

The close of the mission's data-collecting phase was necessitated by Gaia running low on cold gas propellant it uses to spin. The top-hat-shaped craft has been using around 12 grams of this propellent a day since it launched from Europe's Spaceport in French Guiana atop a Soyuz-Fregat rocket on Dec. 19, 2013.

However, even though Gaia may be closing its eyes to the cosmos, this is far from the end of the spacecraft's influence on space science.

"In my mind, the Gaia mission is not ending — just the taking of data," Kareem El-Badry, a Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) researcher and frequent Gaia data user, told Space.com. "I expect Gaia's best results are still to come. That includes in the areas I am most interested in — binary stars and black holes."

Gaia: Gone but not forgotten

Throughout its operational lifetime, Gaia studied almost 2 billion stars and other objects in and around the Milky Way. This vast stellar census contains details of star motions, luminosities, temperatures and compositions.

The aim is to build the largest and most precise 3D map of our local universe. The spacecraft's first data release dropped on Sept. 14, 2016; the second followed on April 25, 2018, and the third (and latest) came out on June 13, 2022.

Gaia's science team won't have time to grieve the loss of Gaia; they are preparing for Gaia Data Release 4 (GR4), which is expected before mid-2026. Based on five and a half years of observations, ESA said that GR4 will not be "more of the same" but rather is expected to trump GR3 in terms of data volume and quality.

Once all of Gaia's data has been downloaded to Earth, work will begin on GR5, the final data release from the spacecraft. This will be a monster data dump containing stellar observations collected over 10.5 years. GR5 isn't expected to be released by the end of the 2020s.

"Less than one-third of all the Gaia data has been published so far, and the final data won’t be science-ready until the 2030s," El-Badry said. "It takes a lot of human and computation work to process the data."

That means we will be reporting on Gaia-based research for some time to come.

That isn't all; Gaia will now become a test subject for scientists aiming to refine spacecraft and instrument control in space.

These tests will run over several weeks while Gaia remains at a gravitationally stable point between Earth and the sun called Lagrange point 2, or L2.

After leaving L2 and its current orbit, Gaia will placed into an orbit that keeps it clear of the Earth-moon system for the near future. In March or April 2025, the Gaia spacecraft will move to its final orbit away from Earth's sphere of influence, preventing it from interfering with other spacecraft.

The ESA said that details about the "passivation" of Gaia and how this pioneering space mission's passing will be marked will be released soon.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.