'2001: A Space Odyssey' Creation and Legacy Probed in 50th-Anniversary Book

"2001: A Space Odyssey" premiered 50 years ago this week, making now a perfect time to look back on the key personalities that created the iconic film.

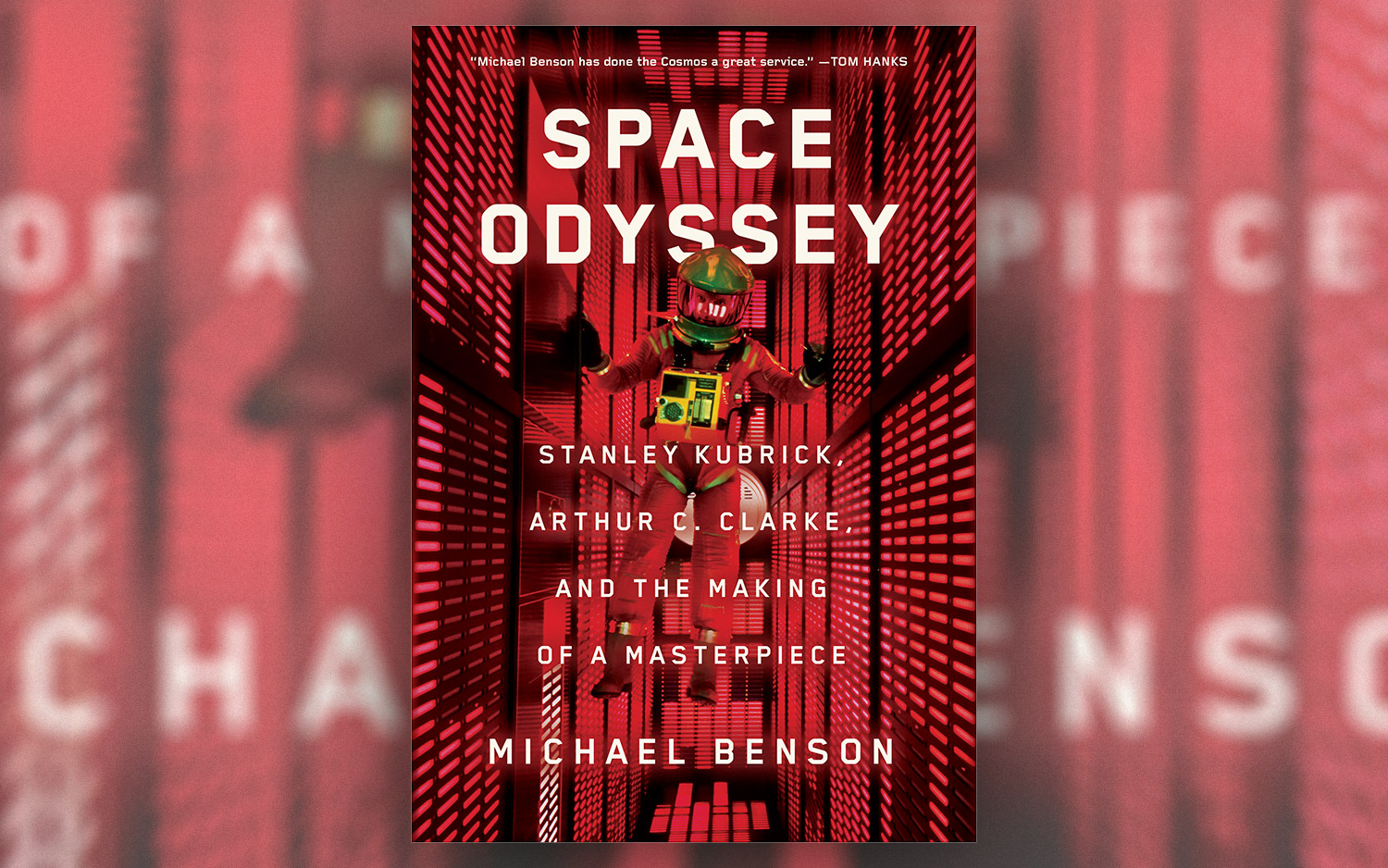

In his new book "Space Odyssey" (Simon & Schuster, 2018), author Michael Benson digs deep into the making of the film, profiling the writer Arthur C. Clarke, the director Stanley Kubrick and the nuances of their partnership, which created the "proverbial 'really good' science fiction movie." Along the way, readers tour the groundbreaking technological developments that made the film possible and the creativity of the large team that lent its ideas and expertise to the project. Readers also get a sense of why the movie remains such a cultural touchstone today. You can read an excerpt from the "Space Odyssey" book here.

Space.com caught up with Benson to discuss his new book, the benefits of the perspective granted by time and the legacy of "2001." [See historical images of the films creation in this "Space Odyssey" gallery]

Space.com: When did you first see "2001: A Space Odyssey"?

Michael Benson: My mom took me to see that film when I was 6 years old, in 1968. I keep on hearing similar stories lately, by the way, about similar life-transforming exposures to "2001" at a young age. It really impressed me on multiple levels. When you're 6 years old, basically, you're very open to new experiences. And it was my first exposure to a masterpiece in any media that really got me where I lived. I didn't come to the idea of writing a book about it until much later.

Space.com: And how did you get that idea?

Benson: I got to know Arthur C. Clarke — I first met him in the year 2001 — and we talked about the film quite a bit. In fact, he wrote the forward to my first book. And I thought, probably right around then, I was thinking maybe I could write something about Arthur and "2001" and so forth. Then, when the 50th anniversary started appearing on the horizon, I thought it might be a good thing to do — it might be, in a way, cathartic, and help me understand the film better [to] write about it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: For the book, you tracked down most of the key players who were still alive and you pored over earlier interview transcripts, letters and even edits to previous work — like Stanley Kubrick's notes on drafts of articles and books about the filming process. Did you get to interact with any physical objects from the filming or from that time period?

Benson: When I was in the Clarke archives at Dulles [the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum], I opened a folder and there was the original letter, written March 31, 1964, from Stanley Kubrick to Arthur Clarke, proposing that they work together to make the first — he wanted to discuss the possibility of doing "the proverbial 'really good' science fiction movie." I suddenly realized, there I was, holding the actual letter — it just kind of — I personally believe "2001" will be talked about in 500 years, that it's going to be one of those works of art that will represent the species in the mid-20th century.

Just to hold the thing, which had some mildew on it because it was in a tropical environment for 45 years or something — it was just amazing. In that sense, I held an artifact. But in a way, I was consciously steering away from film-geek fetishism of object, and I was looking at the written record of what happened: letters, the [telegraph] cables.

Space.com: Does that approach set your book apart from previous coverage of the film?

Benson: Jerome Agel did this book in 1970, [a] very image-heavy, innovative book. When I was a kid, I read this cover to cover many times. It has interviews, it has reviews, it has all manner of vectors into "2001." So, you have Jerome Agel's masterpiece … but it was 1970. There wasn't that much distance from the film. And Piers Bizony did a couple of books, one of them quite good — a lot of images and lots of good research in it. Very image-heavy, with drawings and everything.

I saw my opportunity in a prose-forward, images-following-behind type treatment. It really looked at backstory, got at the detail about the personalities. … That's where I think it's somehow different, taking 450 pages to investigate personalities and the thinking behind it. [Best Space Books and Sci-Fi of 2018: A Space.com Reading List]

Benson: It was really useful to have a record of what people said over decades. It was very interesting. It was kind of a tunnel of gradually deteriorating memories. … It was fun to triangulate between different people's memories. As for the distance — I guess the only way I can really answer your question is to say that I was really grateful that people like Dan Richter [who choreographed the prehistoric segment of the film and acted as the lead man-ape] and Dave Larsen [who co-created a "2001" documentary and provided his transcripts] had really managed to sit down with people who are no longer with us, back when they were still around, and really ask good questions.Space.com: Is there a trade-off between the immediacy of earlier books and the sort of distance you had?

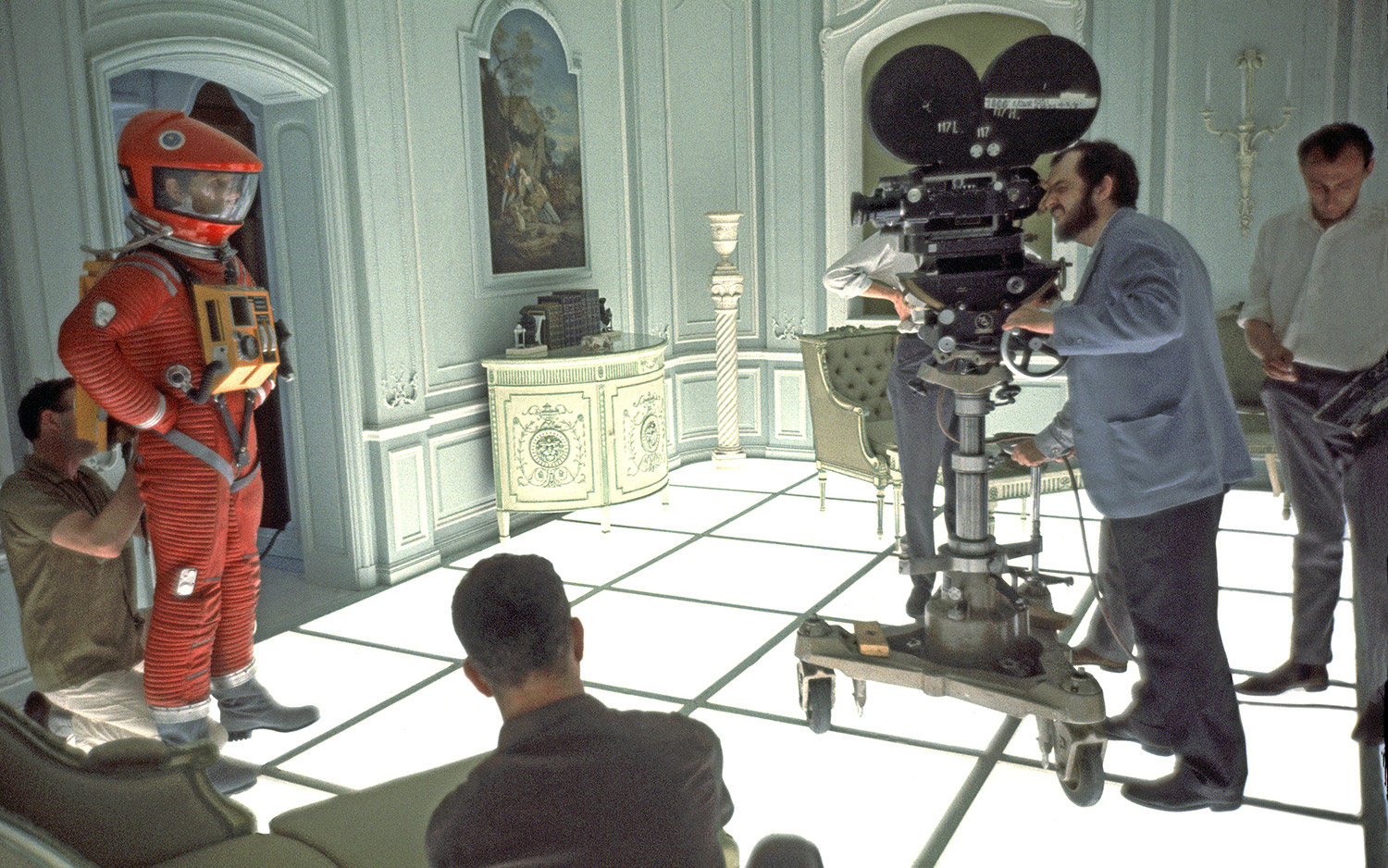

For example, Dave sat down with Bill Weston, the stuntman. That whole section of my book, with Bill Weston dangling 30 feet [9 meters] above the concrete floor on a single wire and almost dying because the wire almost parted, and Bill Weston going unconscious because Stanley wouldn't let him punch holes in the back of his helmet, and therefore he had carbon dioxide poisoning while he was hanging on there — it's just unbelievable — all of that I owe to Dave Larsen providing his interview with the man.

Another point I would make that connects to this question of how much time has passed and, therefore, can you perhaps get to more truth. … When Dave was interviewing him [Weston], Dave referred to Agel's book, stating that [the book said] he [Weston] almost went unconscious, and Weston said, "No, no, I was unconscious. I went unconscious." He corrected it twice. In that sense, sometimes, the more time passes, the closer you can get to accuracy.

I had a lot of fun with Kubrick's notations [on a draft of Agel's book]. You could see stuff he really didn't want to be phrased in a certain way, and that was a telling indicator of some of what he thought, his phobias, his way of being.

Space.com: How do you feel about our progress in space compared to what was portrayed in "2001"?

Benson: I'm with Elon Musk — I think we should be a multiplanet species. Of course, my sensibility was forged by seeing "2001." It seemed like, of course, we're going to expand into the solar system: "Earth is the cradle of the mind, but humanity cannot remain in the cradle forever" [Editor's Note: This quote by Soviet rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was an inspiration for "2001".] And I still feel like that. Unfortunately, we have descended into this — the expense of being so tribal and so warlike has siphoned money from doing such a thing. My ideology, if I can even call it that, from the '70s on: If we could only channel some of this aggression that we exhibit toward each other, if we could just channel it into further expansion, at least we'd be doing that — we'd be going out into the solar system rather than trying to mess with each other all the time. It didn't quite work out that way.

On the other hand, I've found [that] people like Musk, some others, their work to find other reasons to go up there, in other words, commercial — to find reasons other than state-supported, ideologically constrained human space exploration — I find that to be really interesting, and we'll see where it goes.

And then, when it comes to interplanetary, robotics-based exploration, it's been the most extraordinary story. It deserves a lot more attention. It may be that that drama at the heart of "2001" between the computer and the human, with the computer losing — maybe the opposite has happened in actuality, and we're going to have more- and more-sophisticated AI systems going out into space, and that's going to be the way it is. It will be our successors that go out, and they will be AI.

It's already heading that way, isn't it? [The Most Exciting Space Missions to Watch This Year]

Space.com: After writing this book, how do you see the film's legacy?

Benson: I think the film is so much more than just being science fiction and so much more than just being about spaceflight. It's really about our existential position in the universe and our existential position not just in space but in time.

Science fiction is a genre that is considered one kind of thing that doesn't really speak so much to core human concerns in some ways. But science, of course, is so much bigger than science fiction. And science fiction is using science to try to tell stories. It's just up to how skillful you are as an artist, to what extent you can use science to tell a story. What these guys did was so extraordinary. To look back into 4 million years and bring it off, to evolve forward 33 years into this near future, but then to use that as a launching pad to go across space and time in that stargate sequence and the so-called trip sequence. It's occurred to me many times that, in a way, that was a precursor, or premonition, of the Hubble Space Telescope's extraordinary images. When they made that film, we just had grainy color shots from the big Earth terrestrial telescopes where you could sort of sense that … you could get the sense of what's out there, but it was too grainy and fuzzy and all that. What Kubrick himself did with those tanks, the fluids, shooting at high frame rates under bright lights, [mixing] liquids and paints and paint thinner, almost killing himself with the fumes of this stuff, was a precognition of what Hubble brought us and what the bigger telescopes will continue to bring us about the greater universe. All of that, it's just so extraordinary what they brought on.

And to end the whole thing — I mean I'm still blown away by it … It was so visionary and allegorical in the way that a great epic poem can be. No one fixed meaning. That's the reason why we're talking about it now rather than it being some quaint curio of the '60s. There are a number of other science fiction films from the '60s that are not just quaint curios — it's interesting. It's not the only one. But it's just an extraordinary work of art.

I think it belongs in this great tradition of our attempts to grapple with our position in the universe. I did a book a few years ago called "Cosmicgraphics" [Abrams, 2014] which is a look at our attempts to visualize the universe in graphic form. It ["Space Odyssey"] belongs in that tradition, even though it's cinematographic, moving pictures rather than stills. Eventually, we're going to do 3D, three-dimensional visualizations, and all that stuff. But I think it's worthy of it's using the word odyssey. It's kind of worthy of its legacy. Homer would be proud.

This interview has been edited for length.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.