Interstellar interloper 2I/Borisov may be the most pristine comet ever observed

The rogue comet likely never encountered a star before it

The first known interstellar comet to visit our solar system may be the most pristine ever found, never passing near a star until visiting our own, researchers say.

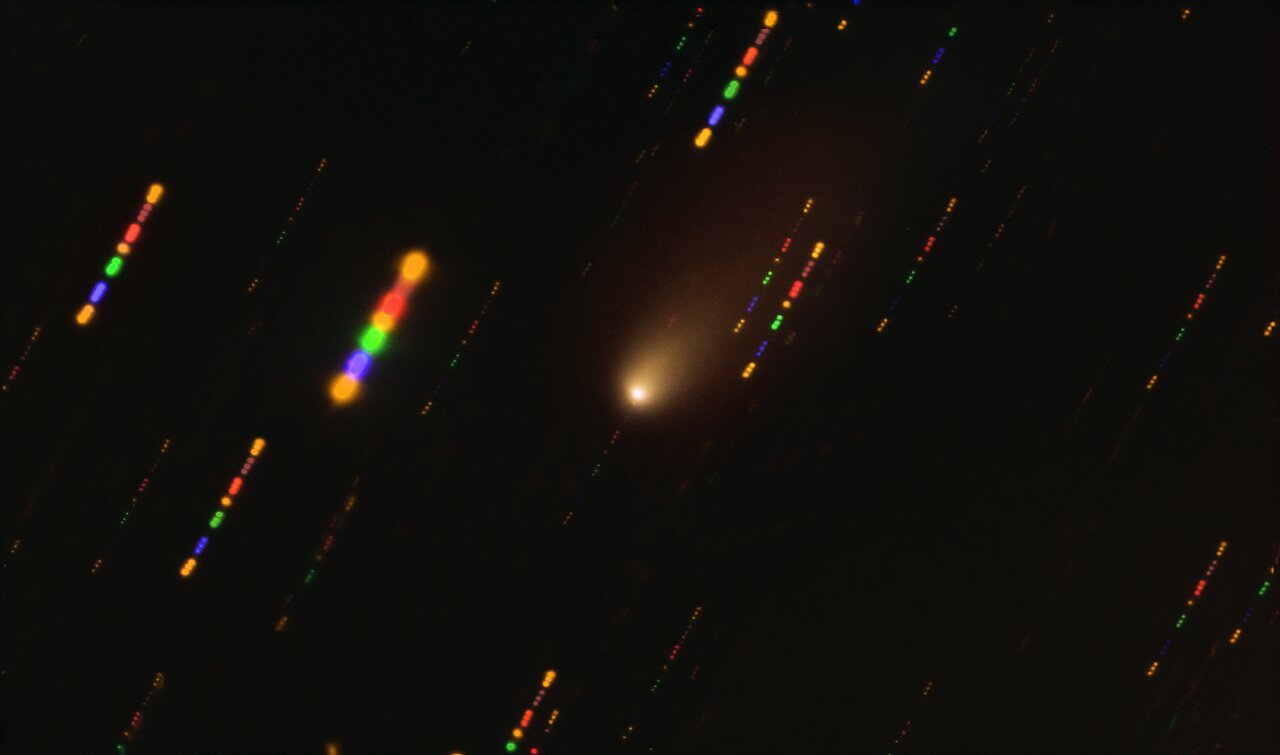

In 2019, scientists discovered the comet 2I/Borisov as it streaked into the solar system. The comet's speed and trajectory revealed it was a rogue comet from interstellar space, making it the first known interstellar comet and the second known interstellar visitor after pancake-shaped 1I/'Oumuamua.

Now scientists have found two new ways in which 2I/Borisov is unlike any known comet. They detailed their findings online March 30 in two studies, one published in the journal Nature Communications and another study in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Video: Alien comet Borisov in incredibly immaculate condition

Related: 'Oumuamua and Borisov are just the beginning of an interstellar object bonanza

In one study, researchers used the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope to analyze light scattered off the dust grains in 2I/Borisov's coma — that is, the envelope of gas and dust surrounding its core. Specifically, they looked at the polarization of this light, or the way in which the light waves rippled through space.

All light waves can ripple up and down, left and right, or at any angle in between. The greater the polarization of light, the more its waves all ripple in the same direction.

When a comet passes close to a star, the radiation and winds from that star can alter the material on the comet's surface, "like our skin when we go to the beach," Stefano Bagnulo, an astronomer at Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland who led the study in Nature Communications, told Space.com. This in turn can reduce the polarization of the light from the comet's coma.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The scientists discovered the light from 2I/Borisov's coma was very polarized, suggesting it was more pristine than other comets — that is, its surface rarely bathed in the light and winds from stars. The only comet that previous research found had light as polarized as the interstellar visitor's was Hale-Bopp, which lit up Earth's sky in 1997.

"Hale-Bopp rarely went close to the sun," Bagnulo said. "We think that before its apparition in 1997, it did it only once, about 4,000 years ago, so the material at its surface, when we observed it, was only slightly processed by the sun."

However, the polarization of light across 2/I Borisov was uniform, while it was not for Hale-Bopp. This suggests 2/I Borisov may be the first truly pristine comet ever detected — it may never have ventured close to any star before it visited the solar system, making it an undisturbed relic of the cloud of gas and dust it formed from.

"The fact that the two comets are remarkably similar suggests that the environment in which 2I/Borisov originated is not so different in composition from the environment in the early solar system," Alberto Cellino, a researcher with the Astrophysical Observatory of Torino in Italy and co-author of the Nature Communications study, said in a statement.

Bagnulo noted astronomers may have an even better chance to study a rogue comet in detail before the end of the decade. The European Space Agency is planning to launch the Comet Interceptor probe in 2029, a spacecraft that will have the capability to reach another visiting interstellar object, if one on a suitable trajectory is discovered, he said.

"Comets that never passed close to the sun are particularly interesting because their material is presumably the same as when our solar system was formed," Bagnulo said. "It is important to study them."

In the other study, to gather clues about the comet's birth and its home system, researchers analyzed data from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile and from the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope.

"We want to know if other planetary systems form like our own, but we cannot study these systems to the level of their individual comets — comets in other planetary systems are simply too far away and too small to be seen by our telescopes," the study's lead author Bin Yang, a planetary scientist at the European Southern Observatory in Santiago, Chile, told Space.com. "We are very lucky that a comet from a system light-years away made such a close visit to us."

The scientists found the dust in 2I/Borisov's coma consisted of compact pebbles, ones 0.08 inches (2 millimeters) or more in width. In contrast, the dust from our solar system's comets typically consists of irregular fluffy clumps of material ranging widely in size from about 0.00008 inches (2 micrometers) to nearly 39 inches (1 meter) wide.

Previous research suggested the solar system's comets formed in a wide region beyond infant Neptune's orbit, and when giant planets such as Jupiter and Saturn migrated to their current positions, their strong gravity slung these comets out to their present locations in the outer solar system.

In contrast, the compact nature of 2I/Borisov's pebbles suggest they were formed during cosmic impacts close to the comet's home star, mashing its matter together into dense chunks, the researchers found. 2I/Borisov was then later slung out into interstellar space by the giant planets orbiting its home star.

In the future, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, due to see first light this year, is expected to detect one interstellar object per year. The European Southern Observatory's Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), currently under construction in Chile, should shed even more light on these interstellar visitors, Yang said. "The future is quite exciting in terms of detecting and characterizing alien objects from other solar systems," she said.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us