Odd supergiant star Betelgeuse is brightening up. Is it about to go supernova?

'When it happens, the star will become as bright as the full moon, except that it will be concentrated in a single point.'

One of the brightest stars in the night sky has been getting oddly brighter, prompting speculations that it might soon explode in a supernova. Should we really look forward to such a dazzling celestial spectacle?

The star in question is Betelgeuse, a huge red-tinged star that sits at the left shoulder of the unmissable constellation Orion. Some 650 light-years from Earth, Betelgeuse usually ranks as the tenth-brightest star in the night sky. Since early April, however, the star has climbed to the seventh spot and currently shines at over 140% its "usual" brightness, according to the Twitter account Betelgeuse Status, which tracks the star's behavior.

Betelgeuse is a red giant, an enormous star that has burned up all the hydrogen fuel in its core and expanded hundreds of times beyond its original envelope. Astronomers believe the star is now fusing helium into carbon and oxygen, a phase in a star's life that lasts tens to hundreds of thousands of years and precedes the star's demise in a supernova explosion. Betelgeuse's recent antics, the beginning of which date back to 2019, have led some to speculate that the moment of its spectacular death might be near. If Betelgeuse were to go boom it would be the nearest supernova explosion in more than 400 years and it would be so bright it would be visible even in daylight.

Related: This new supernova, the brightest in years, could help astronomers forecast future star explosions

The great dimming

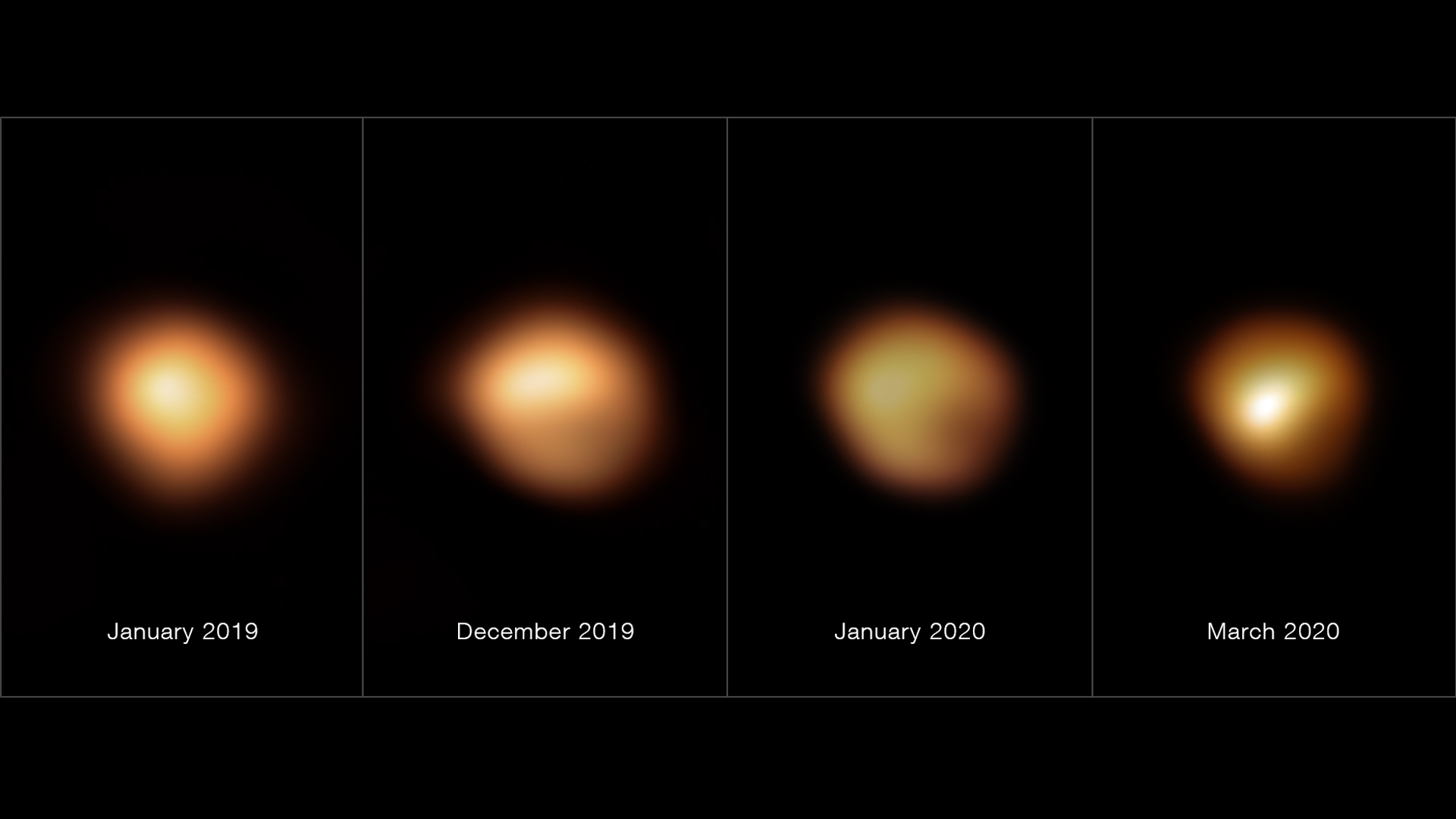

Betelgeuse is a variable star known for regular oscillations between brighter and dimmer periods. For more than 100 years, astronomers have observed Betelgeuse lighten up every 400 days, then drop to about half of its peak brightness and brighten up again. But in December 2019, the star unexpectedly dimmed beyond what had ever been seen before, hitting a low 2.5 times fainter than its usual dimmest shine. The cause of the event, since dubbed the Great Dimming, was later traced to an enormous expulsion of material from the star's interior that created a huge dust cloud that subsequently obscured our view of the star.

End of life

Although Betelgeuse has since recovered its usual brightness, the star has not been quite its old self since the Great Dimming. Its 400-day brightness oscillation period has halved to 200 days and, on top of that, the star now appears to be going through the extra brightening that excites skywatchers. The astronomers that Space.com spoke to, however, are tempering the supernova expectations.

"Our best models indicate that Betelgeuse is in the stage when it's burning helium to carbon and oxygen in its core," Morgan MacLeod, a postdoctoral fellow in theoretical astrophysics at Harvard University and lead author of a recent study about Betelgeuse's Great Dimming, told Space.com. "That means it's still tens of thousands or maybe a hundred thousand years from exploding, if those models are correct."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While a star's regular life ends when it runs out of hydrogen and begins to fuse helium in its core, its expanded life as a red giant lasts beyond the helium-burning stage, explained MacLeod. With helium gone, the star will sustain itself by burning carbon and oxygen into neon and magnesium, then burning those into silicon. Eventually, the star's core fills with iron. And that's when the fireworks begin.

"Adding helium nuclei to an iron atom actually extracts energy rather than gives off energy," said MacLeod. "So all of a sudden, rather than a reaction which is releasing tremendous amounts of energy, the center of the star starts to absorb energy. And when that change happens, the center of the star collapses on itself kind of from the inside out, and then that leads to what we call the core-collapse supernova."

The timescale of stellar death

While the hydrogen-burning phase of a star's life can last billions of years, each subsequent phase is shorter and shorter.

"The helium-burning phase is several hundred thousand years long," Miguel Montargès, a post-doctoral fellow at the Laboratory of Space Studies and Instrumentation in Astrophysics at the Paris Observatory and Betelgeuse expert, told Space.com.

"Then you have the next phase that lasts like 10,000 years, then thousands of years, and then it's a century, and the final one is only some days and hours just before the explosion."

Like MacLeod, Montargès thinks that Betelgeuse still has many thousands of years of life ahead of it and is rather unconcerned by the recent unexpected brightening. In fact, the star has been this bright previously, he said, albeit only for brief periods of time.

"If we compare the current brightening to the Great Dimming, it's really quite negligible," Montargès said. "During the Great Dimming, the magnitude [a measure of a star's brightness that is logarithmic and inversely proportional to the visible brightness] went from 0.8 down to 1.75. The usual peak brightness, on the other hand, is about 0.3, and now we are only at about 0.1."

Back to normal

In the paper, posted on the online repository Arxiv on May 16, MacLeod and his colleagues, rather than expecting a supernova, predict that Betelgeuse will return within the next five to 10 years to its usual ways, slowing its cycle of brightening and dimming to the normal 400 days.

"We think the change in the cycle duration is linked to the event that caused the Great Dimming," MacLeod said. "We think that the huge bubble that burst from the star's interior before the dimming caused the star's envelope and its interior to move in opposite directions, and, as a result, the star is now pulsating twice as fast compared to its normal cycle."

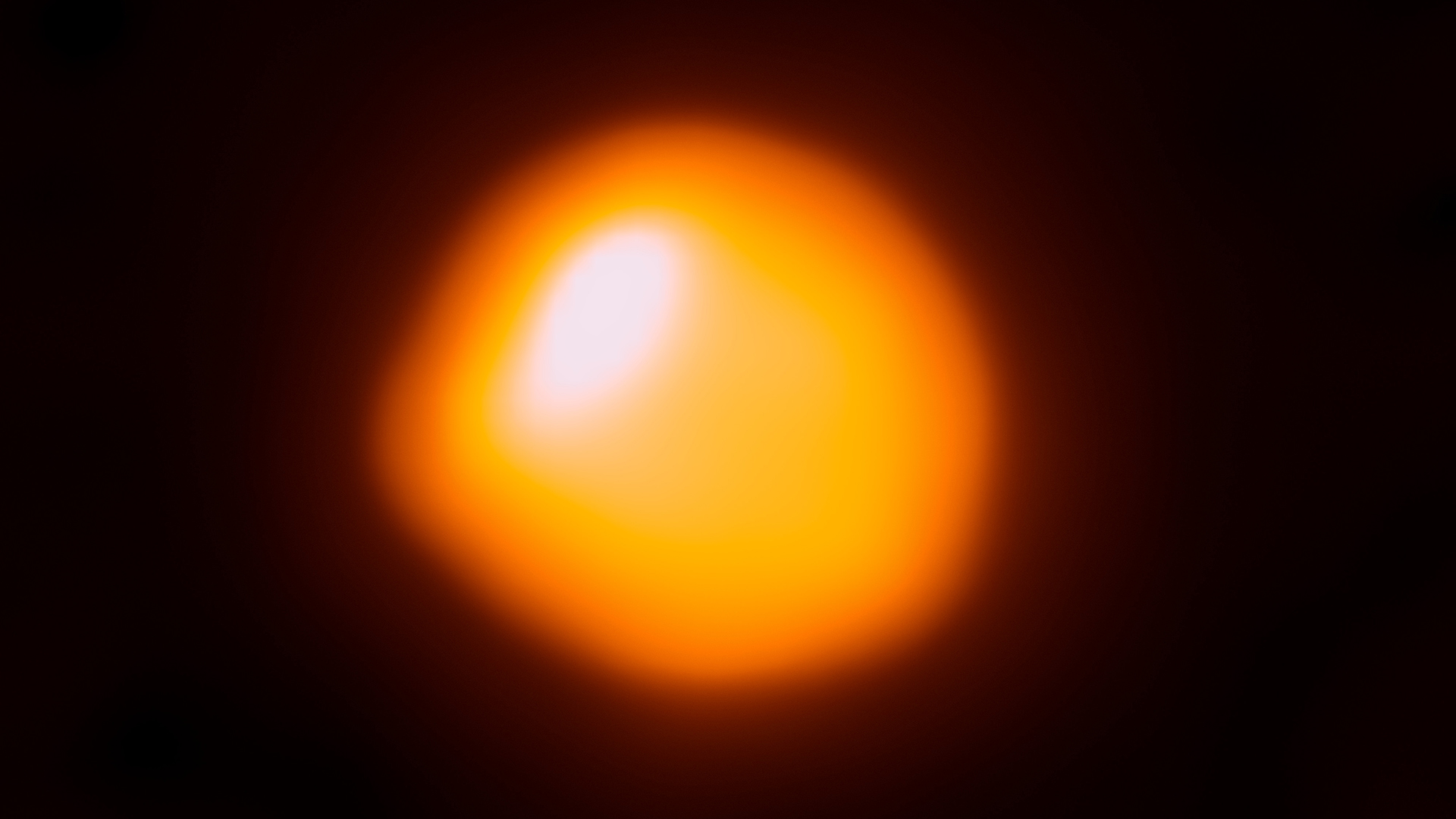

Betelgeuse is an enormous star. If we were to place it at the center of our solar system, it would extend all the way to Jupiter. The star's size, combined with its position in our galaxy, the Milky Way, allows astronomers to study Betelgeuse in better detail than most stars.

"Most stars other than our sun cannot be studied in any detail at all," MacLeod said. "We see them only as point sources of light. But Betelgeuse is big enough that we can resolve it with the Hubble Space Telescope and with radio telescopes."

Those images reveal a striking body quite unlike our sun. Rather than a single smooth sphere of superhot plasma, Betelgeuse is a lumpy clump of boiling gas bubbles, some of them as large as a small star. Huge plumes of hot material rise from Betelgeuse's core to its surface, then cool down and disappear back inside the interior. It's like the sun's cycle on very high doses of steroids. Once every few centuries, Betelgeuse burps out a bubble so large that a Great Dimming ensues. But all that doesn't mean the star is about to explode. Unless, of course, the astronomers' assumptions are wrong.

If Betelgeuse were about to go supernova, would we know?

Thanks to the abilities of our best telescopes, astronomers can see what's happening in Betelgeuse's outer layers so well that they can measure the chemical composition of the star's atmosphere. They, however, have no way of knowing what is really going on inside the star's core. Is it really burning helium? Or has it switched to fusing carbon already? And if it did so, how would we know?

Montargès said that a lot of our assumptions about Betelgeuse come from our observations of other red giant stars. For example, another Milky Way red giant known as VY CMa, located 3,900 light-years away from Earth in the constellation Canis, is thought to be much closer to the moment of its death than Betelgeuse. But unlike the brightening Betelgeuse, that star has been consistently dimming over the past 100 years.

"A hundred years ago, VY CMa used to be visible to the naked eye," said Montargès. "But it has expelled so much material that we can now only see it in infrared. This expelling of material is what we expect to see when the star nears the supernova explosion. VY CMa has already removed about 60% of its original mass, while Betelgeuse still has 95% of its initial material."

The astronomer added that, according to historical records, Betelgeuse used to be described as a yellow star up until 2,000 years ago, when poets began describing it as red. That, Montargès thinks, might indicate that Betelgeuse is only in the earliest stages of its life as a red giant.

Second sun

But Montargès understands the excitement about Betelgeuse's possible death. When the star ultimately explodes, it will make front-page news for months.

"When it happens, the star will become as bright as the full moon, except that it will be concentrated in a single point," Montargès said. "For maybe two months, it will be so bright that if you shut down all the lights in a city and have no clouds, you would be able to read a book in the light of the supernova. It will be so bright that it will be visible in the daylight, too. There will be another star shining in the sky during the day."

Fortunately, although close enough to provide such a spectacle, Betelgeuse is too far away from Earth for its explosion to be dangerous to us. Astronomers think that a giant star would have to blow up within 160 light-years from our planet for us to feel the explosion's effect, according to EarthSky.

The last known supernova to have exploded in the Milky Way galaxy was SN 1604, also known as the Kepler supernova. It was named after astronomer Johannes Kepler, who described it in his book "De Stella Nova."

According to historical records, that supernova, 30 times more distant from Earth than Betelgeuse, remained visible during the day for over three weeks.

Montargès expects Betelgeuse to soon return to within its limits. For the next few months, the star won't be visible, as it will get too close to the sun. Astronomers will have to wait until the end of the summer to check on its progress.

"If in September it's still as bright as now, or brighter, then we should start wondering what's happening," said Montargès. "But from my perspective, I don't think it is that interesting at this stage."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

-

Stevec3608 "Our best models indicate that Betelgeuse is in the stage when it's burning helium to carbon and oxygen in its core," Morgan MacLeod, a postdoctoral fellow in theoretical astrophysics at Harvard University.Reply

Even the most casual search on the internet says that "Of all the elements, helium is the most stable; it will not burn or react with other elements." Morgan MacLeod may have been misquoted. However, wouldn't it have been more accurate to say that Helium is being fused into larger and larger atoms? Then, when the fusion reaction produces Iron, the real fireworks begin? I'm not a Physicist, but this article seems frustratingly inaccurate and poorly written -

Homer10 OK, the Doom Sayers now have another thing to obsess on. It was asteroids wising past Earth at only 1 million miles (that's not even close). Now there will be all sorts of click bait telling us of the impending explosion of this large star. OK, people realize, this is a variable star. It constantly changes it's brightness, getting dimmer, and brighter. There are Hundreds of thousands of variable stars in our immediate vicinity in the galaxy. There are no stars that are close enough to our solar system to cause any problem for the next 10 million years. So, when you see this click bait, just move on.Reply -

LKK Reply

"Helium Burning" is in fact the official term for this event though it's not burning in the normal sense.Stevec3608 said:"Our best models indicate that Betelgeuse is in the stage when it's burning helium to carbon and oxygen in its core," Morgan MacLeod, a postdoctoral fellow in theoretical astrophysics at Harvard University.

Even the most casual search on the internet says that "Of all the elements, helium is the most stable; it will not burn or react with other elements." Morgan MacLeod may have been misquoted. However, wouldn't it have been more accurate to say that Helium is being fused into larger and larger atoms? Then, when the fusion reaction produces Iron, the real fireworks begin? I'm not a Physicist, but this article seems frustratingly inaccurate and poorly written -

billslugg I've searched the peer reviewed literature and cannot find the speed of transition between "zooming" and "whizzing". Still confused.Reply -

Helio Reply

The article stated that fusion was taking place, twice in reference to helium. It is not uncommon to see the use of "burning" in lieu of "fusion" as a slang term since both suggest a before and after effect, and associate heat from burning, which is the later result after gamma rays step down during their path through a star.Stevec3608 said:"Our best models indicate that Betelgeuse is in the stage when it's burning helium to carbon and oxygen in its core," Morgan MacLeod, a postdoctoral fellow in theoretical astrophysics at Harvard University.

Even the most casual search on the internet says that "Of all the elements, helium is the most stable; it will not burn or react with other elements." Morgan MacLeod may have been misquoted. However, wouldn't it have been more accurate to say that Helium is being fused into larger and larger atoms? Then, when the fusion reaction produces Iron, the real fireworks begin? I'm not a Physicist, but this article seems frustratingly inaccurate and poorly written -

Helio Reply

One is louder than the other. It may require you to search a zillion times. ;)billslugg said:I've searched the peer reviewed literature and cannot find the speed of transition between "zooming" and "whizzing". Still confused.