Supermassive black holes in 'little red dot' galaxies are 1,000 times larger than they should be, and astronomers don't know why

"Our measurements imply that the supermassive black hole mass is 10% of the stellar mass in the galaxies we studied."

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have discovered distant, overly massive supermassive black holes in the early universe. The black holes seem way too massive compared to the mass of the stars in the galaxies that host them.

In the modern universe, for galaxies close to our own Milky Way, supermassive black holes tend to have masses equal to around 0.01% of the stellar mass of their host galaxy. Thus, for every 10,000 solar masses attributed to stars in a galaxy, there is around one solar mass of a central supermassive black hole.

In the new study, researchers statistically calculated that supermassive black holes in some of the early galaxies seen by JWST have masses of 10% of their galaxies' stellar mass. That means for every 10,000 solar masses in stars in each of these galaxies, there are 1,000 solar masses of a supermassive black hole.

"The mass of these supermassive black holes is very high compared to the stellar mass of the galaxies that host them," team leader Jorryt Matthee, a scientist at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), told Space.com. "At face value, our measurements imply that the supermassive black hole mass is 10% of the stellar mass in the galaxies we studied."

"In the most extreme scenario, this would imply that the black holes are 1,000 times too heavy."

The discovery could bring astronomers a step closer to solving the mystery of how supermassive black holes with masses millions or even billions of times that of the sun grew so quickly in the early universe.

"Rather than saying this discovery is 'troubling,' I would say it is 'promising,' as the large discrepancy suggests that we are about to learn something new," Matthee added.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: Black holes: Everything you need to know

The story begins with little red dots

Since JWST started beaming data back to Earth in the summer of 2022, the $10 billion telescope has helped astronomers refine their understanding of the early cosmos.

This has included the discovery of supermassive black holes with millions of solar masses when the universe was less than one billion years old. This is problematic, because scientists have estimated that the merger chains of progressively larger black holes and the voracious feeding on surrounding matter that leads black holes to supermassive sizes are thought to take more than a billion years.

Another significant aspect of this investigation of the early universe by JWST has been the discovery of "little red dot galaxies," some of which existed just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, when the universe was around 11% of its current age.

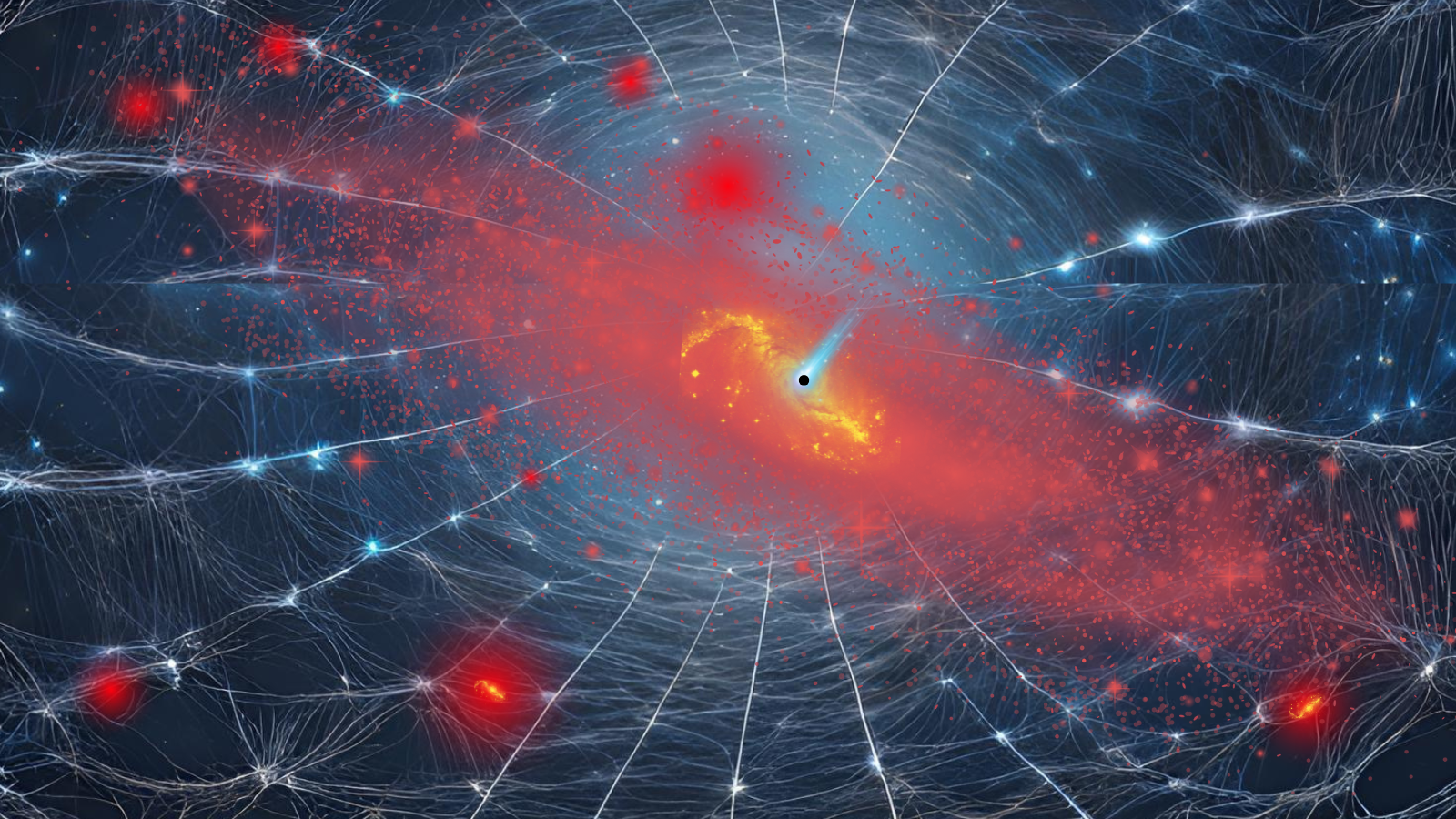

The red coloration of these surprisingly bright early galaxies is thought to come from gas and dust in a flattened cloud of matter around supermassive black holes called an accretion disk. As the giant black holes feed on this matter, they emit huge amounts of electromagnetic energy, from a compact region known as an active galactic nucleus (AGN).

"In 2023 and 2024, we and other groups discovered a previously hidden population of AGNs in the early universe in the first data sets from the JWST," Matthee said. "The light that we see from these objects, in particular the redder light, originates from accretion disks around supermassive black holes.

"These objects became known as 'little red dots' because that's how they appear in JWST images."

Currently, this early galactic population is very exciting, albeit poorly understood. For instance, in the early universe, little red dots seem to be far more numerous compared to previously known populations of AGNs seen from Earth as supermassive black hole-powered quasars.

Related: What is the Big Bang theory?

"The little red dots also show some very remarkable properties, such as the faintness in X-ray emission, which is pretty unusual for AGNs, and the infrared emission is also unusual," Matthee said. "Due to these complications, we are struggling to interpret the light that we observe from the little red dots, which means that it is very difficult to study their properties."

This is where Matthee and colleagues' new work comes in. Using a data set from the JWST year 2 (cycle 2) “All the Little Things (ALT)” survey, the team built a precise 3D map of all galaxies in a specific region in the sky.

"Within that region, we have identified seven little red dots, similar to previous studies, but now we have been able to compare the locations of these little red dots in the 3D galaxy map," Matthee said.

The team's little red dots are located so far away that their light has been traveling to us for around 12.5 billion years. They are clustered in the so-called cosmic web of galaxies, with their positioning being of paramount importance.

Little red dot galaxies are morsels on a cosmic web

The position of galaxies in the cosmic web depends on the type of galaxy. More evolved, massive galaxies are found in over-dense regions such as the nodes where the strands of the web connect. Younger and lower-mass galaxies tend to be found in less dense regions of the cosmic web, along the length of individual strands away from nodes.

"We have found that the little red dots are in environments that resemble low-mass, young galaxies," Matthee said. "This implies that the little red dot galaxies are also low-mass young galaxies."

The fact these little red dot galaxies contain AGNs has provided evidence that early black holes are actively growing in galaxies with stellar masses as low as around 100 million times that of the sun.

One possible explanation for this is that supermassive black holes in the early universe managed to form and grow much more efficiently than those in the present-day universe. This could be due to the more rapid consumption of surrounding gas and matter.

"In my opinion, the most likely explanation is the extremely rapid growth of supermassive black holes nurtured by the high gas densities of galaxies in the early universe," Matthee said. "These densities simultaneously lead to high stellar densities, which promotes supermassive black hole formation through facilitating runaway collisions of remnant black holes."

If that's true, then the formation of stars and supermassive black holes in galaxies are intrinsically linked, with these processes depending on each other. Though supermassive black holes grow faster in early galaxies, star formation catches up, leading to the 1:100 mass ratio seen today.

This doesn't yet confirm rapid growth theories over other supermassive black hole growth explanations, such as the idea that these cosmic titans grow from massive black hole seeds created by the direct collapse of huge clouds of gas and dust.

However, Matthee added that it will now be hard for theorists to get around low host galaxy masses when competing theories are considered.

Matthee explained that the next steps for both the team and for the wider astronomical community are to eliminate the possibility that the stellar mass/black hole mass ratio they found is not the result of inaccurate measurements or a selection bias that may have favored the most active and thus massive supermassive black holes.

This will likely involve the discovery of more little red dot galaxies, a hunt that the JWST will undoubtedly be at the heart of.

"The JWST has been important for two main reasons: Without it, we would not have discovered those populations of faint AGNs," Matthee concluded. "Also, without the JWST, we would not have been able to make the accurate 3D map of galaxy distributions that we used to infer the properties of the galaxies hosting the faint AGNs.

"It’s a very exciting research field at the moment!"

The team's research has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal. It has been posted on the paper repository site arXiv.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

contrarian What is surprising about this article is the age of the LRDs quoted at 1.5 billion years after the BB. Other sources indicate they formed much earlier, with apparent ages of only 600-800 million years*. They seem to 'disappear' around 2 billion years after BB. It is likely they simply acquired more hydrogen/helium to grow into more regular galaxies. M87's SMBH might even have been a LRD very early in its formation and evolution.Reply

In any event, the appearance of these LRDs and other AGNs in the early Universe tend to suggest that galactic core BHs could have formed by different mechanisms, and at least some (if not all) by direct collapse immediately following the BB.

* /forbidden-black-holes-jwst-tiny-red-dots -

finiter Our cosmology is based on straight line motion of light. If its path has a slight curvature, say a radius of 2.5 billion light years, then we will have to rewrite the whole cosmology. Then, light rays will be convergent, magnifying the brightness of distant galaxies millions of times. Then, the estimated masses of the black holes based on brightness and light-travel distance will be highly inaccurate.Reply