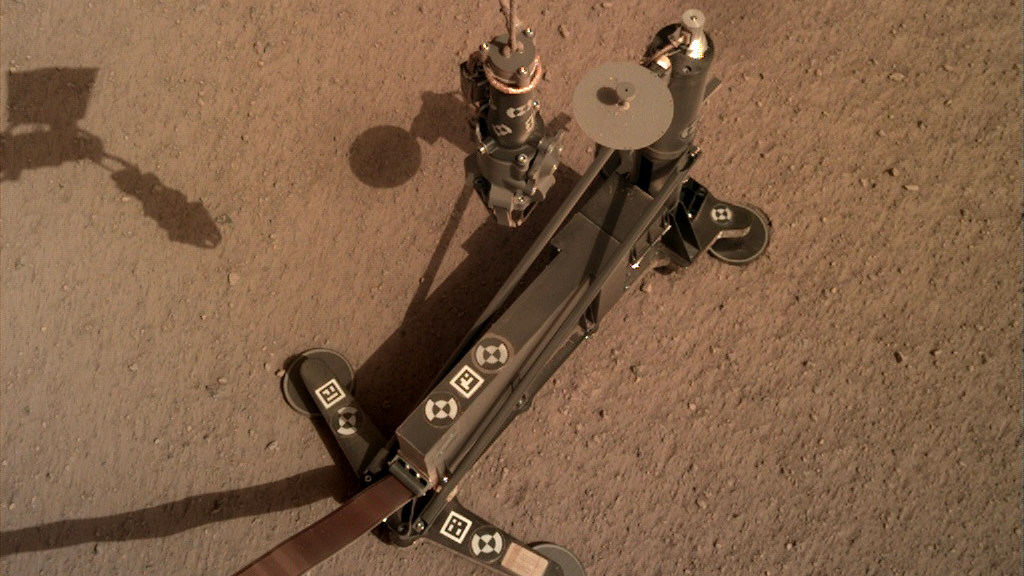

The "mole" aboard NASA's InSight Mars lander has encountered stiff resistance on its first subsurface sojourn beneath the surface of the Red Planet.

In a major mission milestone, InSight's Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument burrowed underground for the first time on Feb. 28. After 400 hammer blows over the course of four hours, the instrument apparently got between 7 inches and 19.7 inches (18 to 50 centimeters) beneath the red dirt — but obstacles slowed its progress, mission team members said.

"On its way into the depths, the mole seems to have hit a stone, tilted about 15 degrees and pushed it aside or passed it," HP3 principal investigator Tilman Spohn, of the German Aerospace Center (known by its German acronym, DLR), said in a statement.

Related: Mars InSight in Photos: Looking Inside the Red Planet

"The mole then worked its way up against another stone at an advanced depth until the planned four-hour operating time of the first sequence expired," Spohn added. "Tests on Earth showed that the rod-shaped penetrometer is able to push smaller stones to the side, which is very time-consuming."

I’m digging #Mars! My self-hammering mole has started burrowing in, and my team is poring over the data I’ve sent them. They estimate it may be around 35 cm (14 in) down. More hammering to come, as I investigate the inside of Mars.🌡 More from @DLR_en: https://t.co/FsmfN0WVpa pic.twitter.com/CRHFDp6ouKMarch 1, 2019

The $850 million InSight lander — whose name is short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport — touched down on Nov. 26. The spacecraft aims to map the Red Planet's interior in unprecedented detail.

It will do this primarily by characterizing "marsquakes" and other vibrations with a suite of supersensitive seismometers, which was built by a consortium led by the French space agency CNES; and measuring subsurface heat flow with HP3, which DLR provided.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In a Mars-exploration first, InSight placed both of these instruments directly on the Martian dirt using its robotic arm. The seismometers do their work on the surface, but HP3 needs to go down — much deeper down than it's managed to get so far. The mission team wants the mole to get between 10 feet and 16.5 feet (3 to 5 meters) underground when all is said and done.

"The mole will pull a 5-meter-long tether equipped with temperature sensors into the Martian soil behind it," DLR officials wrote in the same statement. "The cable is equipped with 14 temperature sensors in order to measure the temperature distribution with depth and its change with time after reaching the target depth and thus the heat flow from the interior of Mars."

The digging process will take time, even if the mole finds its way through the current rough patch. Burrowing generates heat that would compromise HP3's measurements, so the instrument pauses to cool off for two Mars days after each four-hour hammering session. It then records temperatures for a day before burrowing again, DLR officials said. (One Martian day, or sol, lasts about 24 hours and 40 minutes.)

InSight's surface mission is designed to last for at least one Martian year, which is equivalent to 687 Earth days.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.