As new probes reach Mars, here's what we know so far from trips to the Red Planet

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Tanya Hill, Honorary Fellow of the University of Melbourne and Senior Curator (Astronomy), Museums Victoria

Three new spacecraft are due to arrive at Mars this month, ending their seven-month journey through space.

The first, the United Arab Emirates’ Hope Probe, made it to the Red Planet last week. It will stay in orbit and study its atmosphere for one complete Martian year (687 Earth days).

China’s Tianwen-1 mission also entered orbit this month and will begin scouting the potential landing site for its Mars rover, due to be deployed in May.

If successful, China will become the second country to land a rover on Mars.

These two missions joined six orbiting spacecraft actively studying the Red Planet from above:

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- NASA's Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and MAVEN Orbiter

- Europe's Mars Express

- India's Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM)

- the European and Russian partnership ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter.

Book of Mars: $22.99 at Magazines Direct

Within 148 pages, explore the mysteries of Mars. With the latest generation of rovers, landers and orbiters heading to the Red Planet, we're discovering even more of this world's secrets than ever before. Find out about its landscape and formation, discover the truth about water on Mars and the search for life, and explore the possibility that the fourth rock from the sun may one day be our next home.

The oldest active probe - Mars Odyssey - has been orbiting the planet for 20 years.

Read more: How to get people from Earth to Mars and safely back again

The third spacecraft to reach Mars this month is NASA’s Perseverance rover, scheduled to land on February 18. It will search for signs of ancient microbial life but its mission also looks ahead, testing new technologies that may support humans visiting Mars one day.

Laboratories on wheels

NASA has an impressive track record for landing on Mars. It has operated all eight successful missions to the Martian surface.

What began with the two Viking landers in the 1970s continues today with the InSight lander, which has studied the daily weather on Mars and detected Marsquakes for the past two years.

Perseverance will be the fifth rover to arrive on Mars that’s capable of venturing across the surface of another planet.

These amazing laboratories on wheels have extended our knowledge of a faraway world. Here’s what they’ve told us so far.

The first rover - Sojourner

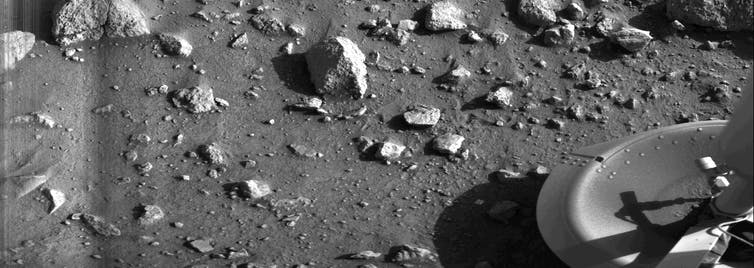

Twenty years after Viking 1 & 2 landed stationary probes on Mars, a third spacecraft finally reached the planet, but this one could move.

On July 4, 1997, NASA’s Pathfinder literally bounced onto the Martian surface, safely enclosed in a giant set of airbags. Once stable, the lander released the Sojourner rover.

The first rover on Mars could move at a maximum speed of 1cm a second and was about as long (63cm) as a skateboard — smaller than some of the boulders it encountered.

Sojourner explored 16 locations near the Pathfinder lander, including the volcanic rock “Yogi”. Pictures of its landing site, Ares Vallis, showed it was littered with rounded pebbles and conglomerate rocks, evidence of ancient flood plains.

The geologists - Spirit and Opportunity

A pair of upsized rovers arrived on Mars in early 2004. Spirit and Opportunity were geologists, searching for minerals within the rocks and soil, hidden clues that dry, cold Mars may once have been wet and warm.

Spirit landed in Gusev Crater, a 150km-wide crater created billions of years ago when an asteroid crashed into Mars.

Spirit discovered evidence of an ancient volcanic explosion, caused by hot lava meeting water. Small rocks had been thrown skyward but then fell back to Mars. Examination of the impact or “bomb sag” showed the rock had landed on wet soil.

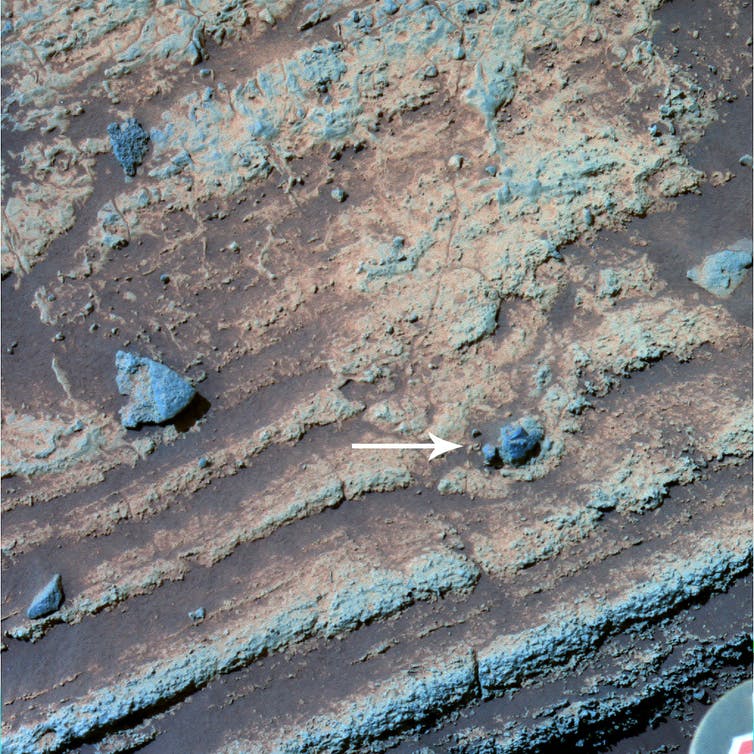

Even when things went wrong, Spirit made new discoveries. While dragging a broken front wheel, Spirit churned up a track of soil revealing a patch of white silica.

This mineral usually exists in hot springs or steam vents, ideal environments where life on Earth tends to flourish.

The rover that kept on going

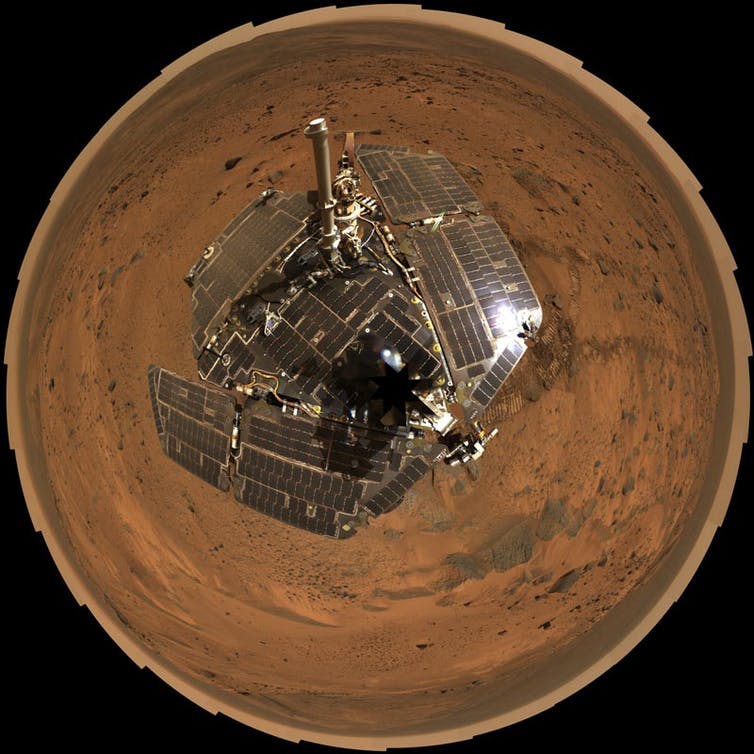

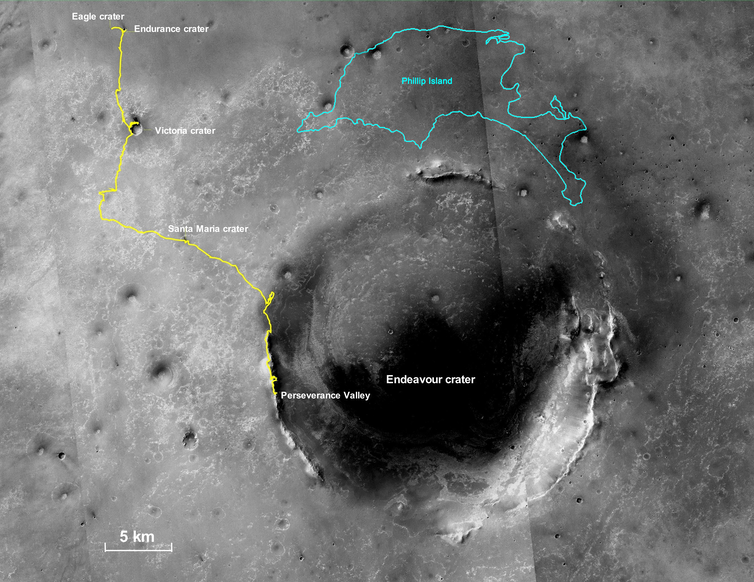

Opportunity arrived on Mars three weeks after Spirit. Its original three-month mission was extended to 14 years as it travelled almost 50km across the Martian terrain.

Landing in the small Eagle Crater, Opportunity went on to visit more than 100 impact craters. It also found a handful of meteorites, the first to be studied on another planet.

The rover was descending into Endeavour Crater when a dust storm ended its mission. But it was along the crater’s edge that Opportunity made its biggest discoveries.

It found signs of ancient water flows and discovered the crater walls are made of clays that can only form where freshwater is available — more evidence that Mars could well have been a place for life.

The chemist - Curiosity

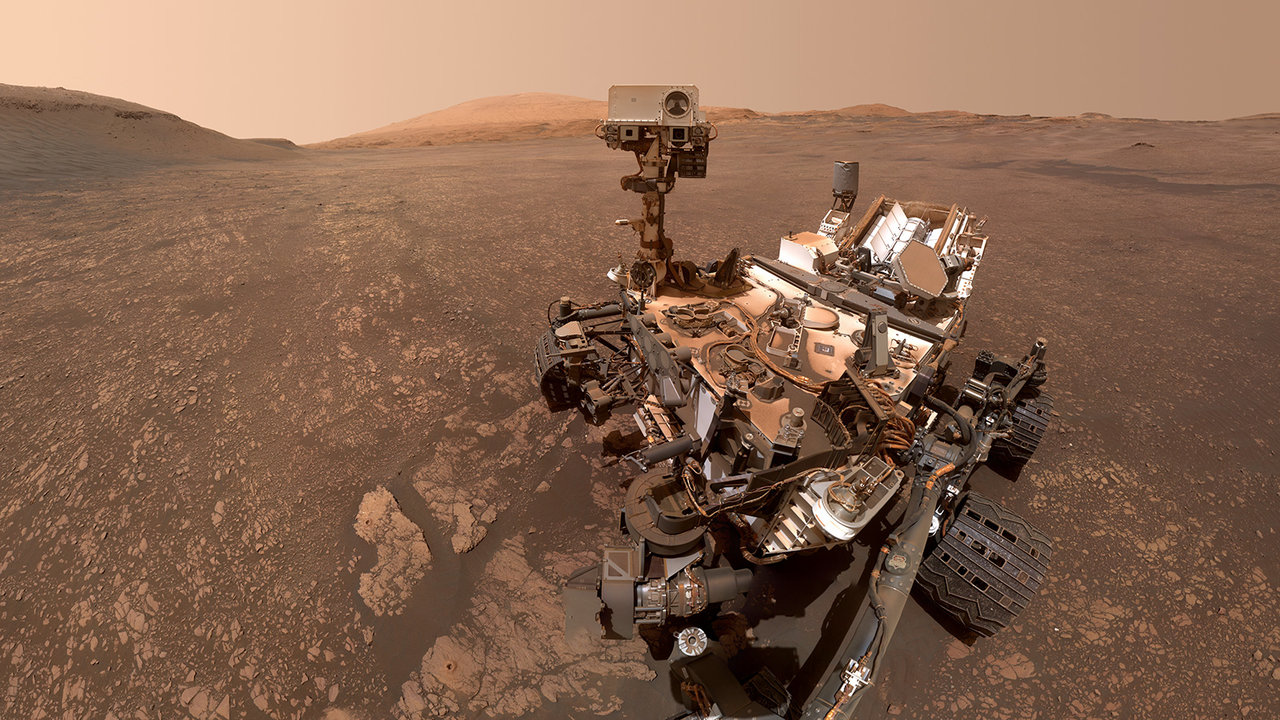

Curiosity landed in Gale Crater on August 6, 2012, and continues to explore the region today. During the coronavirus pandemic, scientists and engineers have been commanding the rover from their homes.

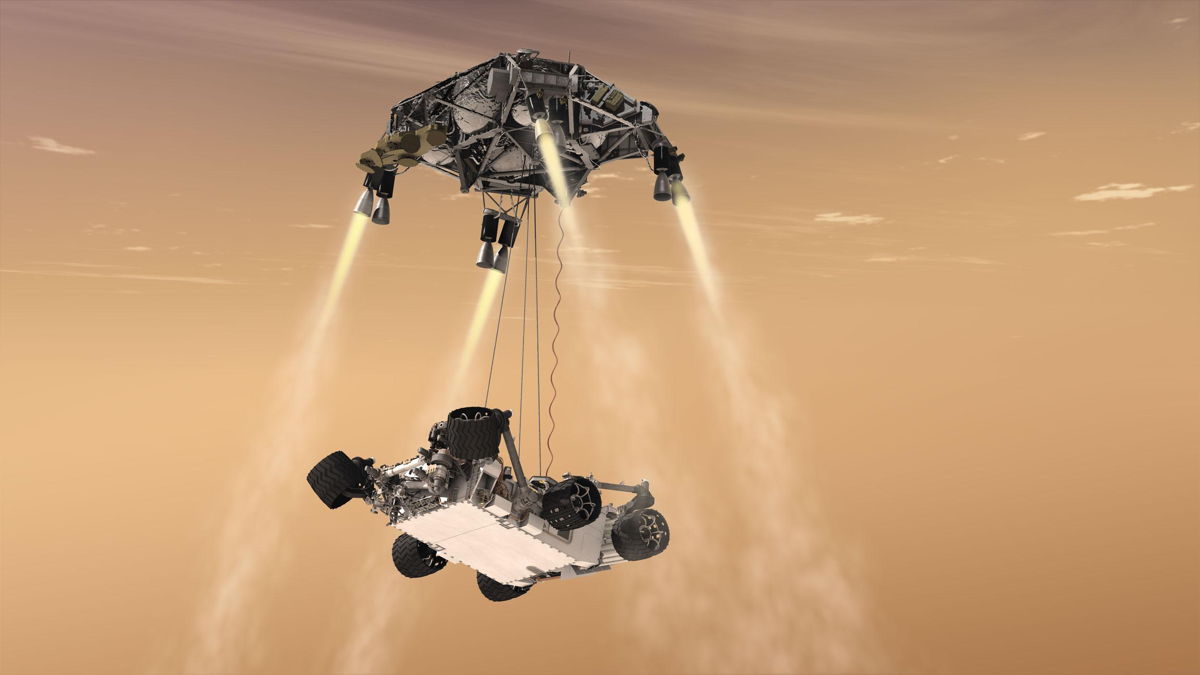

In a first for space exploration, NASA’s Curiosity was lowered to the Martian surface using a “sky crane”. After a successful soft landing, the crane’s cables were cut and the spacecraft’s descent stage flew away to crash elsewhere.

Curiosity is a fully equipped chemical laboratory. It can shoot lasers at rocks and also drill into the soil to collect samples. It’s confirmed ancient Mars once had the right chemistry to support microbial life.

Curiosity also found evidence of ancient freshwater rivers and lakes. It seems that water once flowed towards a basin at Mount Sharp, a central peak that rises 5.5km from within Gale Crater.

From being on the surface of Mars, we’ve learned it was once very different to the dry, dusty planet it is today.

Read more: The Conversation Weekly podcast Ep #1 transcript: Why it's a big month for Mars

With flowing water, possible oceans, volcanic activity and an abundance of key ingredients necessary for life, the red planet was once much more Earth-like. What happened to make it change so dramatically?

It’s exciting to consider what the Perseverance and Taiwen-1 rovers may discover as they explore their own patch of Mars. They might even lead us to the day when humans are exploring the red planet for ourselves.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

I am an extragalactic astronomer, Honorary Fellow of the University of Melbourne, and am currently working in the field of science communication at Melbourne Planetarium.

I have been the Curator (Astronomy) at Melbourne Planetarium, Scienceworks since 1999, drawing on my background in research astronomy to create more than a dozen planetarium productions. The most recent of these are now screened in over fifty planetariums across sixteen countries world-wide.

I am proud to be the Australian Representative of the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Science Outreach Network. This sees me working with Astronomy Australia Limited (AAL) to promote ESO’s extensive research accomplishments throughout Australia.

I am also involved in projects to bring research astronomy data into the planetarium to both engage the public and to turn the planetarium into a tool for research astronomers wanting to know more from their data.